These Aussies are shaping our future. Here’s what it means to your family

What began as a unique family study to track a generation of Victorians is now set to help shape the future health of the nation.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

What started as a project to track a generation of Victorians is set to help shape the future health of the nation.

Generation Victoria (Gen V) was brought to life by 120,000 Victorians from nearly 50,000 families who gave samples such as saliva, breastmilk and blood, including DNA, to help researchers answer questions about our health, how we live and the impact of where we live.

This data will help uncover everything from what happens under the skin to how climate change can impact health now and into the future.

It is already being used to identify and solve complex health problems from whether blood pressure checks should begin in childhood to who is likely to have a heart attack by the age of 50.

Three years on the project is about to go national and become Generation Australia.

This will be a one-stop-shop with a “treasure trove” of population health data made freely available to researchers worldwide.

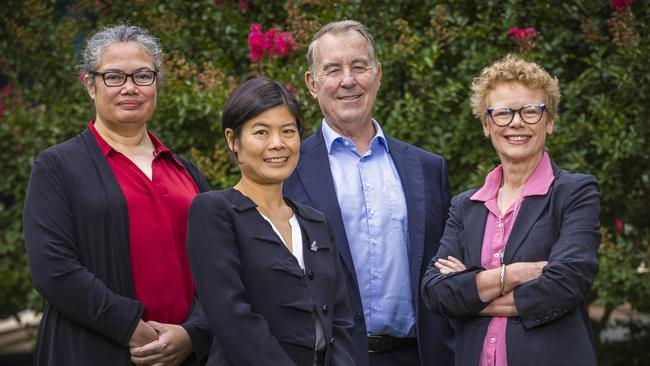

Gen V scientific director Professor Melissa Wake says taking the initiative national will make it one of the great studies of its time, because the results will apply to everybody.

She says to think of it as a living laboratory, one that will not only save time and money, but help solve the “big and connected health and social problems” facing families today.

Other projects under way are looking at how to prevent chronic disease such as cancer, preventing hearing loss and intellectual disability to improve outcomes for Australian children and ways to address anxiety and depression in parents of preschool children.

Teams are also using the data to predict neurodevelopmental disorders to enable earlier intervention and developing healthier starts for children with lifelong impact.

The mechanisms between urban heat and mental health are also under the microscope.

In the spotlight for Generation Australia will be mental health, climate, obesity and heart health.

“But there is a whole range of different issues, all of which can come to this one-stop shop,” Professor Wake said.

Gen V is led by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) supported by funding by the Paul Ramsay Foundation, the Victorian Government and Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) Foundation.

It aims to attract additional funding for Generation Australia to make it the largest birth and parent cohort study globally. It will be a combination of various cohorts and state-held data, driven by the research leads of each separate study.

Professor Sharon Goldfeld, Deputy Scientific Director of Gen V and Director of the Centre for Community Child Health at the RCH, said Generation Australia was needed as the current pace of research was too slow to keep up with the modern health and social challenges for Australia’s children and their families.

“The current policy environment offers real opportunities for benefit, but we need to know what works for which families and under what circumstances, or we just risk increasing inequality,” Professor Goldfeld said.

“Generation Australia will accelerate cost-efficient research of global importance to identify new therapies, reduce service delivery costs, and tailor care for children and families to create better and more equitable children’s health, development and wellbeing outcomes.”

MCRI environmental epidemiologist and health geographer Dr Suzanne Mavoa is using the data to understand how the places that we live, work and play can improve the health of children and families.

More importantly, she said, was how and where to intervene in those environments to make a difference.

“The exciting thing about Gen V is that it’s tracking such a large population across diverse environments,” Dr Mavoa said. “And we’re tracking how the environment changes over time and that’s the information you need to be able to make those recommendations.

“What science can do, and what Gen V can help us do, is to understand what we can do about it.”

Gen V will partner with other family studies across the nation such as ORIGINS, a West Australian cohort of 10,000 women and their families that has been running for eight years and offering real-time opportunities for intervention.

Blending them into a national study will, says pediatrician Professor Desiree Silva who co-leads ORIGINS, be a way to ensure parents have all the necessary information and supports to raise their children.

“By coming together, we are going to add value to help answer lots of different questions that the government might have around health. So essentially, there’s a huge cost saving,” she said.

Professor Silva said researchers now won’t have to start from scratch when setting up a project because the data will already be there and ready to go.

ORIGINS has been investigating the rising rates in children of allergies, asthma, mental health, anxiety, ADHD, autism, and obesity.

“The research that we’re targeting is looking at understanding why this happening, and then what we can do about it,” Professor Silva said. “Our research is about real-time feedback, picking it early and directing families to early intervention so that they can get the treatment they need.”

Professor Wake said the next five years was about maturing the Generation Australia platform.

“We will be able to start answering questions around what’s the prevalence of issues that are really important, especially for policy, especially for families,” she said.

Melbourne mum Saada Houli and daughter Mya, almost two, were among the first recruits to the Gen V project.

“I think research is very important because how else are we going to be able to progress or make changes or change things down the road?” Mrs Houli said. “All generations need to be a part of important research.”

On the opposite side of the country, Archer and his parents Bryanna and Mitchell are part of the ORIGINS study that, unlike Gen V, requires participants to attend regular in-person appointments.

At a visit with a pediatrician as part of the study Archer did an early childhood test that identified he had global developmental delay.

He has now received an autism spectrum diagnosis and his family the appropriate funding to support speech therapy, physiotherapy and allied support for timely early intervention thanks to the study.

Researchers like MCRI epidemiologist Professor Terry Dwyer say the data collected will save lives and solve future health problems like cardiovascular disease.

He says this is important because cardiovascular disease kills 40,000 people a year and Australia spends an extra $12 billion a year because of the current occurrence.

Rates, he said, were going up.

“So we’ll start to see, again, a fall in life expectancy in Australia because cardiovascular disease makes up so much of the deaths,” Professor Dwyer said.

“This is a disease we can do something about, but all our energies have been focused for the last 50 years on health campaigns for adults.”

He said blockage of the arteries starts in childhood and a solution that could be tested using Generation Australia data may be to monitor children for early signs of the risk factors for heart disease then load up several interventions simultaneously to reduce that risk.

“This (project) will save lives substantially,” he said.

More Coverage

Originally published as These Aussies are shaping our future. Here’s what it means to your family