How social media is fuelling a deadly eating disorder epidemic

Eating disorders claimed the lives of 1273 Australians last year and as the number of sufferers surges, experts warn social media use is driving a deadly epidemic.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Social media is fuelling a deadly epidemic that is killing more people every year than the road toll.

Eating disorders claimed the lives of 1273 Australians last year with anorexia nervosa the nation’s deadliest out of all mental illnesses.

More than 1.1 million Australians, including one in five teenage girls, have an eating disorder but health professionals fear many people are suffering in silence, with fewer than one in three reaching out for help.

Experts warn that toxic body image content is contributing to an alarming 200 per cent surge in cases among 10 to 14 year olds and a 76 per cent increase among those aged 15-19 year-olds since 2012.

Desperate parents, academics and health professionals have joined the push to raise the age young people can access social media platforms, saying algorithms are preying on vulnerable adolescents who have concerns about their appearance.

Butterfly Foundation CEO Dr Jim Hungerford says there has been a dramatic increase in body image concerns and eating disorders diagnoses, including a 275 per cent increase in calls to its national helpline over the past five years.

Dr Hungerford says it is “absolutely horrifying” that almost one in five girls in their late teens had an eating disorder.

“Social media is a large driver of body image concerns,” he said.

“It really is developing into a crisis.

“If everybody did come forward (for help) it would just absolutely smash the health system. So it’s something we have to act on.”

The public health crisis is costing Australia a whopping $67bn a year, with the federal government forking out $4.7bn, according to Deloitte.

Dr Hungerford said greater regulation was needed to ensure social media platforms rapidly take down harmful material, adding better age verification was needed and users should be able to control what they get to see.

“Social media is a large driver of body image concerns,” he said.

“It really is developing into a crisis.

“If everybody did come forward (for help) it would just absolutely smash the health system. So it’s something we have to act on.”

The public health crisis is costing Australia a whopping $67bn a year, with the federal government forking out $4.7bn, according to Deloitte.

Dr Hungerford said greater regulation was needed to ensure social media platforms rapidly take down harmful material, adding better age verification was needed and users should be able to control what they get to see.

“We need to make sure that those algorithms don’t promote harmful content,” he said.

What lies at the core of eating disorders

Eating disorders are a serious mental illness not a lifestyle choice.

There are at least eight different types of eating disorders including anorexia, bulimia and binge eating.

Women are twice as likely to experience an eating disorder, which can be caused by a combination of factors including genetics, psychological and societal factors.

People with autism spectrum disorder are also more likely to have an eating disorder, which can play into their liking of rules and order, numbers and control.

Experts say it involves an unhealthy relationship with food, such as the belief people mustn’t eat or the compulsion to eat.

People put excessive focus on their body shape or weight and use their appearance to define their self-worth.

An eating disorder voice can also emerge, telling the person that they are not good enough, they have to try harder, they have failed and have to punish themselves.

However, research shows that social media is a large driver of body image concerns, which can lead to disordered eating.

The number of people being diagnosed with eating disorders soared during the Covid pandemic when people’s social media use increased, and they panicked about putting on weight because they were stuck in lockdowns.

How does social media affect us?

“Imagery is really a powerful communicator to our brain, it’s much more powerful than the spoken word in terms of influencing emotion, which is why it has to be managed so carefully on social media,” Flinders University Prof Tracey Wade said.

“Kids can know that it (images) has been doctored and it’s not real, but they they still have this strong pool to try … to look like what they see in the media.”

Prof Wade said the brain’s frontal lobe continued to develop until people were 25 years old and the pictures were addictive because it gives young people an oxytocin hit.

“They say ‘oh, this is my purpose, this is what I can do, I can work towards this’,” she said.

“This is why it makes sense when people are saying that we should ban social media for kids until they turned 14 or 16.

“The developing brain is actually quite susceptible and gets hooked.”

Who is to blame?

Four in five carers of people with eating disorders believe social media contributed to the eating disorder, its development, or it had hampered recovery efforts.

That’s the shocking findings of an Eating Disorder Families Australia (EDFA) survey following Covid.

Chief executive Jane Rowan said while social media may not have been the factor that started the illness, it had made it more difficult.

She said parents were drowning in their plight to monitor the content their children see on social media.

“Parents are really crying out for some help, we’re struggling,” Ms Rowan said.

“It’s like trying to stop a tsunami on most days and when you’re up against that algorithm, and it’s impossible.

“Instagram, obviously, has been the main contender for a long time … in more recent years, it’s probably shifted more to TikTok.

“Cyber bullying … and self harm, a lot of that’s coming through on Snapchat.”

Ms Rowan said she had first-hand experience of kids using Snapchat to share photos criticising other people’s appearances, “writing horrible, hateful things on them (and) sending them around”.

“Kids think that they can get away with it because the pictures vanish so quickly,” she said.

“The language is vile. It’s quite horrifying. It’s going to get scarier with AI.”

One South Australian mother, whose daughter was diagnosed with an eating disorder two years ago at age 11, said she had seen first hand the “significant impact” social media had on developing eating disorder thoughts.

“I remember my daughter always watching YouTube videos about stretching her body for almost one year,” she said.

“The girl teaching on YouTube is very slim. It constantly portrayed the message that the ‘ideal female body should be thin’.”

Ms Rowan said EDFA was advocating for social media platforms to immediately remove any damaging content, such as pro-anorexia, pro-self harm and cyberbullying, as well as raise the age of access.

More than two in three respondents to a recent EDFA survey said social media should not be allowed until 14 years or older.

“I just don’t see any other way of protecting our young people effectively, before the damage is done,” she said.

“Social media should be treated like alcohol, it should be illegal until they’re 18.”

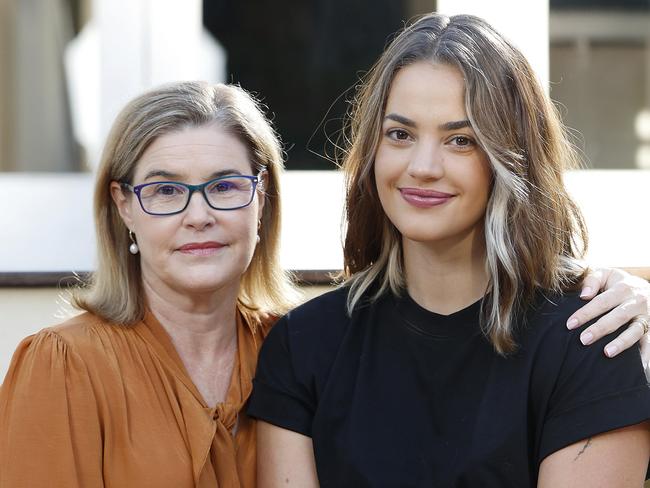

‘I was constantly seeing girls promoting diet fads’

University student Isabella Charon says increased social media use during the Covid pandemic ultimately triggered her eating disorder.

Ms Charon, 20, says she spent quite a bit of time on TikTok and Instagram, which kept showing her negative body image content posted by influencers, models and athletes.

“It was hard to escape from everything because I was just surrounding myself with really bad messages about body and food,” she said.

“I was constantly seeing girls promoting diet fads.

“That made me think I had to do it as well … being a vulnerable teenager, you know, and being isolated.

“So ultimately, that’s what triggered my eating disorder.”

Ms Charon was diagnosed with anorexia in 2021 and has since unfollowed the accounts of people she “idolised” for her eating disorder.

As part of her healing journey, she now follows accounts that promote body positivity.

She said there needed to be a discussion about what content was appropriate for users aged under 18 because people who were not qualified were spreading “dangerous” information about diets and exercise to young people who will “believe anything they see”.

“They just need to actually engage directly with these influencers to make sure that there’s no misinformation,” she said, adding controls about what can be promoted were also needed.

“They obviously have a community, but not always for the right reasons.

“It’s just all about being ethical, even though it’s easier said than done.”

She said athletes and models should know that everyone’s bodies were different and depend on their lifestyles, but instead they often mask eating disorder behaviours under a supposed “healthy lifestyle”.

“It’s very unnecessary to post what you eat in a day because in the end, it’s not really going to make you look like that person,” Ms Charon said.

She said encouraged Instagram users to spend time away from the explore page and follow people who were inspiring and positive about food and body image.

BUTTERFLY FOUNDATION: 1800 33 4673

LIFELINE: 13 11 14

Originally published as How social media is fuelling a deadly eating disorder epidemic