Mortuary train took dead bodies to Rookwood Cemetery from 1867 until 1938

From 1867 to 1938, the richest Sydney residents along with the poorest were taken to be buried the same way — by a special train to Rookwood Cemetery.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

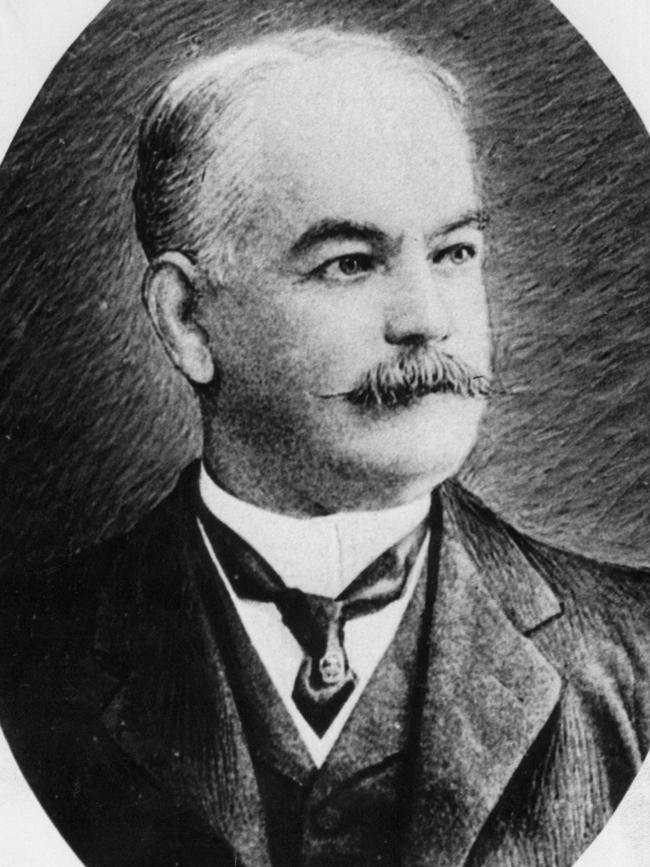

On a warm winter day in 1909 thousands of people crowded the streets between Darling Point and Central Station in Sydney to witness the funeral cortege of the much-loved merchant retailer Samuel Hordern.

The crowds grew thicker the closer to Central the four-horse hearse drew and three special trains had to be employed to take the 2000-odd employees of Anthony Hordern & Sons to see their beloved employer laid to rest at Rookwood.

When the mortuary train carrying the oak coffin of Samuel Hordern arrived at Rookwood’s No.1 Receiving Station, newspapers reported it was difficult to clear a path to the merchant’s gravesite.

That he was laid to rest with such pomp and pageantry was no surprise, although it was considered one of the biggest funeral corteges in the state’s history.

And while Hordern’s funeral spared no expense, the means of getting his body to the gravesite was the same as it was for even the poorest of citizens.

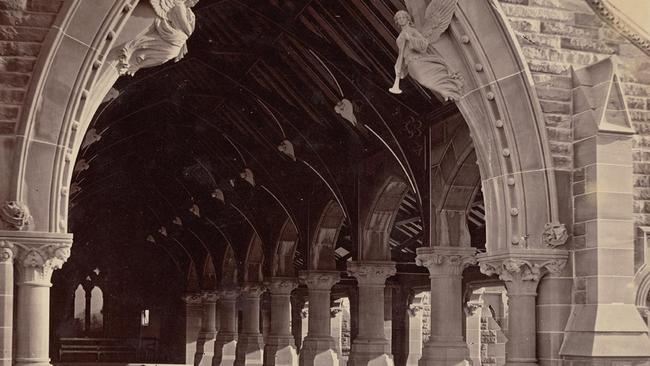

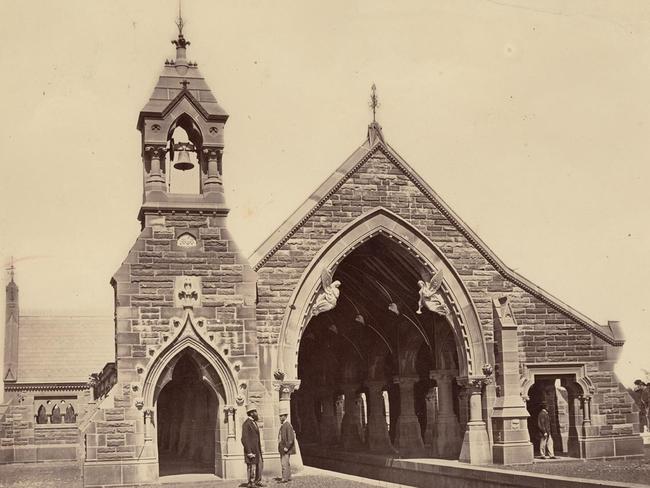

The No.1 Receiving Station at Rookwood was built in 1867. The impressive gothic structure designed by Colonial architect James Barnett out of Sydney sandstone depicted angels, cherubs, fruit and flowers.

And through its grand arches most of those who were buried at Rookwood between 1867 and 1938 arrived – the richest Sydney residents along with the poorest.

The special mortuary train ran a twice-daily service to Rookwood, first from Central Station and then from the Regent Street Mortuary Station in Redfern. The fare was advertised at being one shilling return for mourners and free for corpses.

Rookwood is the largest Victorian cemetery still operating in the world and when it opened in 1867 it was a destination in the late-Victorian tradition of “tending and spending” the day at the cemetery.

In the days before grand public parks and museums were available for the masses, a day out at the cemetery was common. As one newspaper put it, they were a place of “pensive or festive resort”.

And just how festive a visit to the cemetery became was up to the mourners.

“The celebration of life would often begin from the time the mourners got on the train,” says Rookwood historical tour guide, Mark Bundy.

“The wake would be held at the cemetery, the food and alcohol sometimes placed right on top of the coffin. There were even reports of people throwing chicken bones and the like into the grave to show their loved ones what a great send off they had for them.”

Bundy says the way people responded to death in the late-Victorian era is vastly different to today. It was not uncommon for people to use beautiful big garden-like cemeteries like Rookwood to picnic and stroll arm-in-arm along its avenues. In an online article in 2018, American author Jonathan Kendall quoted a man in 1884: “We are going to keep Thanksgiving with our father as though he was as live and hearty this day as last year; we’ve brought something to eat and a spirit lamp to boil coffee.”

Bundy says: “It used to be a big thing to come out to Rookwood, like a family outing where you could visit the gravesite of a relative, tend their grave and then enjoy the parklands, maybe have a picnic. People would get dressed in their Sunday best.

“The Victorians had a different sensibility to life and death, in a time when death was so common and so many were taken before their time, it was nice to still have a connection with a loved one after they’d passed.”

As Rookwood Cemetery grew – first from 200 acres to an eventual 740 acres – three more receiving stations were added so mourners could get to their designated gravesite within the vast grounds easily. But, by the 1930s, as cars were becoming more popular, there was less call for the mortuary stations and the No.1 closed in 1938. Today, you can still see the foundation of the platforms and columns of this once-grand and important structure.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

STATION’S BLESSED GOOD FORTUNE

After Receiving Station No.1 closed, it fell into disrepair and was often the site of drug parties and home to vagrants.

The government threatened to demolish it and use the crushed sandstone in road construction. But in 1957 the Church of England’s Reverend Buckle from the ACT saw an ad for the old station and bought it for £100.

A parishioner, Stan Taunton and his son, camped out in Rookwood for four months laboriously numbering each brick, which were transported to Canberra on 83 semi-trailers and rebuilt over a year.

All Saints Anglican Church, Ainslie, opened and was dedicated in 1959. It was consecrated in 1975.

LIVING KEEP THEIR DISTANCE

In 1862 when the state government bought 200 acres of land at Haslems Creek and once the Necropolis Act was passed in 1867, a cemetery was established there.

But as the Haslems Creek Cemetery grew, so too did the local residents’ distaste for sharing a name with a burial place.

By 1878, Rookwood was being commonly used, believed to have been chosen because there were many crows in the area, and the local railway station and suburb were renamed accordingly.

But by 1913 residents of Rookwood again wanted to distance themselves with the cemetery’s name and the suburb that today borders the necropolis was renamed Lidcombe.

HOME BREWER’S JOURNEY TO PADDINGTON BEER BARON

If you lived in Sydney in the second half of the 19th century and liked to enjoy the odd beer or two, chances are you were familiar with Marshall’s Paddington Brewery.

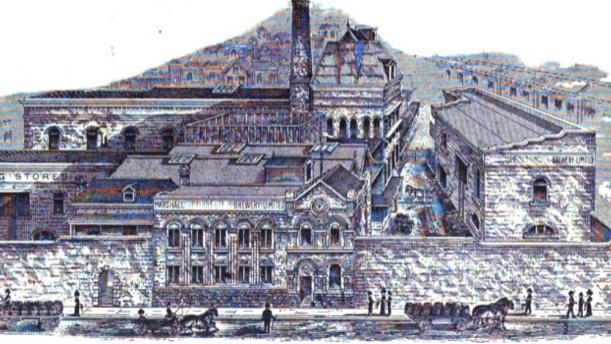

On the site where Oxford St intersects South Dowling St and Barcom Ave, entrepreneur Joseph Marshall built what was known at the time as the largest brewery in NSW.

Few who walk past the derelict site today would know of this history, though the street that runs behind the site — Marshall St — hints at this early history.

Rather it is mostly remembered today as the site of the old West’s Olympia Theatre which was built on the site of the demolished brewery in 1911.

But a new development will once again see the beer flow on the site as it opens its doors as a new $100m boutique hotel at the end of 2022.

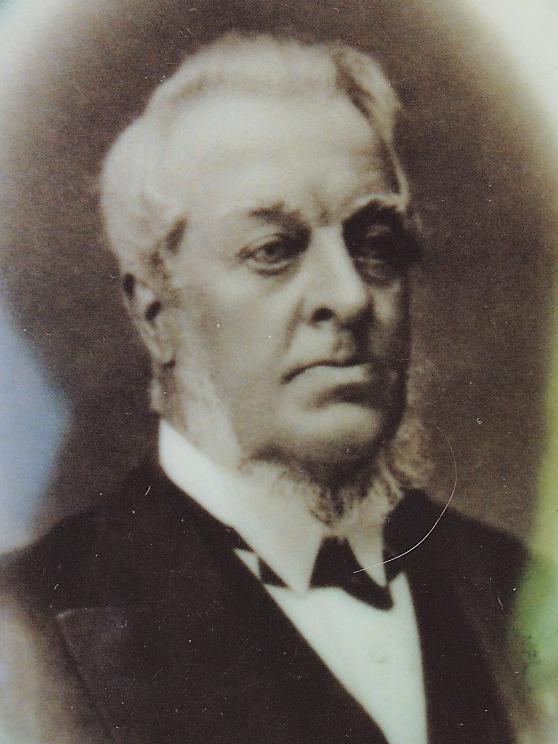

Joseph Marshall arrived in Australia from England in 1840 at the age 22. He lived briefly in South Australia before settling in Sydney where he established himself as a drug wholesaler at 3 George St, Sydney.

“He came from a very established family in Yorkshire who had made their fortune through mills,” says author and historian Caroline Hardie.

“Shortly after arriving in Australia he married Esther Robinson who was also from Yorkshire. Her family were landed gentry and her father, George Robinson, is said to have been a friend of King George IV and entertained him at his property at Huddesfield, Yorkshire.

“The couple were considered to be ‘colonial gentry’ and were listed in Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Colonial Gentry.”

They built a home at what is today 1-11 Oxford St, Paddington, a two-storey property they named Beaumont Villa, though the structure was not as grand as the name implied. And in 1856, the savvy businessman opened a brewery on the site.

“He started doing his own brewing as a hobby and his friends enjoyed what he produced and urged him to expand,” Hardie says.

“It became quite a commercial enterprise, the biggest and most productive brewery in Sydney at the time, and he also owned dozens of pubs throughout Sydney and NSW who sold his beer.”

His beer picked up various awards at agricultural shows, including first prize at the Intercolonial Exhibition of 1876. But brewing wasn’t Marshall’s only enterprise.

In 1860, he bought the machinery needed to can fish and sailed it up to Lake Macquarie himself in a schooner.

It was a region that would have had very little road or other infrastructure at the time, and he established what would become a successful fish cannery plant, bringing tinned whiting, flathead, bream, snapper, salmon-trout, mullet and guardfish to the people.

Canning fish was a relatively new enterprise given the first fish was only canned in Scotland in the 1830s.

The Duke of Edinburgh’s visit to Sydney in 1867 was a major cause for celebration and one merchant ran a newspaper advertisement titled Prepare For The Prince in which “Marshall’s preserved fish” was mentioned among champagne, preserved ginger and 20-year-old Scotch whisky.

The Marshall family album featured a photograph of the prince, so you can only guess the family were included in social parties welcoming him to the colony.

In 1866, Marshall also started growing sugar cane, predominantly to service his Sydney brewery, establishing 60 acres near the Central Coast. But a fire swept through the land in 1875 destroying the entire crop.

And he invested in a gold mine at Tambaroora near Bathurst and a copper mine in Northern Cobar.

All of it was supplemented by an extensive property portfolio that included real estate throughout Sydney and NSW.

Marshall died in 1880 and was survived by three sons, who continued to run the brewery, and a daughter.

The brewery was bought in 1911 by Tooth & Co who quickly closed it as a way of eliminating competition.

The site was redeveloped and became West’s Olympia Theatre, which remained until the most recent redevelopment which promises a six-storey premises with rooftop premises.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

SYDNEY’S BOOMING BREWERIES

Kent Brewery was opened in 1835 by the newly arrived English brewer John Tooth and his brother-in-law Charles Newnham on Parramatta Rd at Broadway.

They acquired several breweries throughout the 20th century, including Resch’s Beer and Castlemaine Brewery, and went on to become one of the most successful breweries in Australia.

At their height, they owned more than 700 pubs and developed the popular KB Lager (named for Kent Brewery).

Tooth & Co was sold to Carlton & United Breweries (CUB) in the 1980s, and that company still produces KB Lager. Kent Brewery was closed in 2005.

CHEERS TO NEW LIFE AT THE MOVIES

When West’s Olympia Theatre opened in 1911 with the American silent film The Power Of Love, it was a two-level theatre seating 2500.

In the 1920s it was renovated and reopened as Union Theatres and reputed to show Sydney’s first talkies.

By the 1930s it came under Greater Union and in the 1950s it was again renovated and renamed The Odeon before closing in 1960.

It would remain shut until 1969 when it opened as the art house Mandala Theatre and ran for three years.

In 1973 it became Sydney’s first suburban twin cinema, The Academy Twin, which closed in 2010.

Originally published as Mortuary train took dead bodies to Rookwood Cemetery from 1867 until 1938