The smell hits first – a mix of chemicals and decay – followed by the sight of still pink wounds and charred black skin. For Dr Chris Lawrence, this sensory overload was once a daily reality.

“I’d argue a forensic pathologist isn’t normal,” he says pragmatically. “How could they be?”

Over 35 years, he pieced together the stories behind deaths that shocked, saddened and confounded not only their families and police, but the world. Yet for him, it was never about the gruesome details, or even the science – it was about solving a mystery.

While most people could find a few faults with Australia – from high house prices to near- stagnant wage growth – when it comes to gaining experience in the challenging field of forensics – Dr Chris Lawrence has some unusual grumbles.

“Really, one of the problems here in Australia is you don’t see a lot of shootings,” he says, now retired and living on a vineyard outside Hobart with his family and a couple of dogs.

“Traumatic stuff, sharp knives and bashings, they’re the same the world over. But shootings are complicated and you need some experience.”

Experience is something Dr Lawrence has in spades.

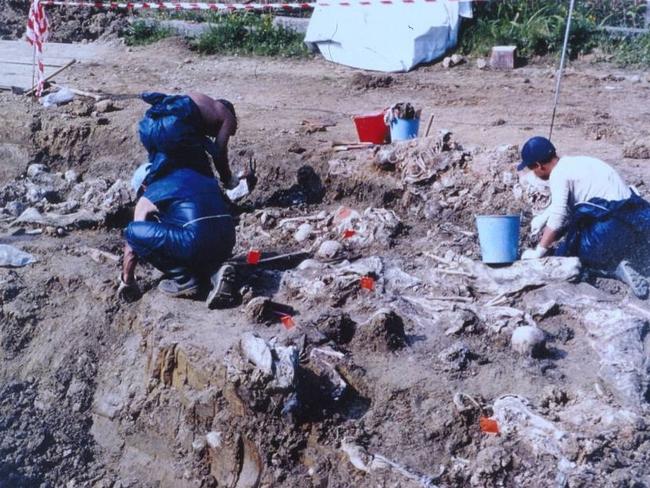

From performing autopsies on the bodies at Port Arthur and the executed boys and men of Srebrenica, to studying the victims of serial killers and the drug mafia, there’s little about the how and why of death that has escaped his scrutiny in his long career.

Born in Adelaide, Dr Lawrence, 66, blue-eyed and self-effacing, followed his medical family into the profession. He retired at 65 after working in Tasmania’s forensic service since 2002, and spent 18 years as the state forensic pathologist.

“The thing about Chris is, he truly never gives up,” says fellow forensic pathologist Neil Langloise, speaking from South Australia.

“The mystery and the puzzle of a death has always spurred him on. I really think he could have made a great detective.

“And he has a lot of compassion too, which is so important in this profession.” But after decades of dealing with the aftermath of sadistic murders, massacres and natural disasters, symptoms of PTSD began to intrude.

“When New Zealand asked me to come over for the Christchurch massacre I said ‘No’ – I just couldn’t face it,” Dr Lawrence says.

“Everything had started to catch up with me.”

FROM PORT ARTHUR TO SREBRENICA

From the early days of his medical degree, Dr Lawrence was more interested in solving the mystery of patient deaths than in treating their illnesses.

“A police friend of mine once said, ‘There’s a detective in everybody’. And I think that’s true.” he says.

As remains the case today, few people were practising as forensic pathologists in Australia when Dr Lawrence trained in the 1980s. They were deterred by the relentless and confronting unpleasantness of autopsies.

“It’s tedious, it’s messy, it’s smelly,” he says. “But your nose adjusts to the smell in about 10 minutes.”

After qualifying and also studying law, Dr Lawrence shifted to Albuquerque, New Mexico. The move was strategic, with the US having one of the highest rates of homicidal shootings in the western world.

Within two years, he had developed specialist skills in identifying gunshot wounds. These skills were called upon in 1996, when he was chosen as part of a three-person forensic team to conduct autopsies on the victims of the Port Arthur massacre, in which 35 people were killed.

“I’ve never seen a disaster affect a community quite so much,” he remembers.

“I did my last case a few hours before I jumped on the plane and flew back to Sydney. And I had an acute stress reaction. I went back to work straight after it, no break, no time to decompress. For a long time I thought I’d got through it. But I hadn’t.”

In Sydney, Dr Lawrence worked for 13 years at the mortuary in Glebe, a densely populated, inner-city suburb.

It was here he examined the final victim of the Granny Killer, as well as the body of INXS frontman Michael Hutchence.

The interest in the pop star’s death was intense and the mortuary was forced to lock the autopsy photos in a safe when they found out $1m was being offered for their sale.

“The problem with the high-profile ones is, no matter what you do, you’re going to get punished,” Dr Lawrence says.

“I think the problem with Michael Hutchence is, they probably should have called us out to the scene to examine it. It would have answered more questions. They should have dealt with it like a homicide. It’s less suspicious if we were called out. And it’s very hard to disprove a conspiracy theory later, once everything’s done.”

A LONELY CALLING

After 13 years working as part of a team in the busy Glebe morgue, Dr Lawrence was lured to Tasmania by a leadership role, and became the state’s sole forensic pathologist for nearly five years.

The independence of the job was welcome, but the physical reality of trying to inspect scenes all around the state – including at the Beaconsfield mine collapse in 2006 – led to Dr Lawrence working closely with police to upskill their forensic officers in processing the scene.

Today, forensic pathologists rarely visit crime scenes to examine a body first-hand. Instead, they collaborate with forensically trained police officers on-site, who relay images and video to the mortuary and provide real-time descriptions of what they observe.

It’s an industry where much has changed and also very little. Many of the gangland and drug killings are still “unsolvable”, Dr Lawrence says, but the police force has also cleaned up its act, and the feminisation of the police and forensic pathology “has made both professions better” he says.

Over a long career, there are some cases he will never forget.

Working on the Srebrenica massacre for the United Nations and giving evidence at The Hague that saw a war criminal convicted “was a career highlight”, he says. Though performing autopsies on 900 of the 7000 dead men and boys in a makeshift field mortuary was a test of stamina and resilience.

Baby autopsies and severe sexual assaults are the hardest to perform, Dr Lawrence says, particularly when called on by the court to give detailed evidence of their injuries in front of their grieving families: “I hate that.”

People whose deaths remained mysteries for months or years have also stayed with him.

The three bodies found in a burnt-out house in Sydney, each with a bullet wound – a longstanding question of who shot whom? The court case and subsequent appeals took 15 years to answer that.

The 11-year-old girl who died from gastrointestinal issues but was found to have a yellow, fatty liver – a clue that puzzled Dr Lawrence for 12 months. Eventually, he discovered she was the product of incest between her mother and grandfather, with her liver disease caused by a recessive hereditary condition passed down by her related parents.

And the healthy young pilot who dropped dead in Antarctica of a suspected heart attack, but who had actually been huffing chemicals after strained interpersonal issues on the frozen continent.

These are the cases Dr Lawrence still reflects on as he tends his vines, meditates and occasionally sees a grief counsellor.

“It was never just a job for Chris, his whole mind was captured by it. He wouldn’t stop until he had found out what happened,” says colleague Mr Langloise.

Dr Lawrence’s last cases are making their way through the courts, and he is approaching a time when the only deaths he will witness will be replays in his mind.

“I think there have been moments when I just get a bit sad and sort-of go off on my own,” he says.

“The thing that I still don’t know is how the hell you deal with it? I mean the job has got to be done. I suspect that you probably should only do a certain number [of autopsies].”

For Dr Lawrence, much of his career is the product of dodging boredom – shying away from medicine he found dull, and towards stories where he didn’t know the ending, and the dead couldn’t speak.

His restless, probing nature and decades of experience have earned him a reputation as one of Australia’s most respected forensic pathologists – one whose expertise is rarely questioned by his peers.

“There’s a certain dark fascination with forensics, and sometimes I think there’s information people don’t need to know,” Dr Lawrence says, staring out at his vines.

So you keep it?

“I keep it.” •

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Statewide total fire ban with wild winds set to sweep through

Tired firefighters are bracing for more dangerous fire conditions after a total bushfire ban has been announced for Tasmania.

‘Learning curve’: TSO goes digital

The TSO is regarded as one of the leading small orchestras in the world. Read how musicians are embracing new technology.