‘It’s like throwing a child into war’: Mother says her son was changed by the Ashley Youth Detention Centre

A mother has revealed her son was denied crucial medication while at Ashley Youth Detention Centre, and suffered “repercussions” from staff every time she called to complain.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN Norman* came out of the Ashley Youth Detention Centre, he was a different person to the boy who’d gone in.

His mother Eve* said staff refused to give him his bipolar medication, saying they needed to have their own psychiatrist – who visited from the mainland every six weeks – assess him themselves.

The youth workers told his mother Eve* that instead, they’d strip Norman down without his medications, so the psychiatrist could see him “in his natural state”.

The fallout was huge.

Giving evidence to the child sexual abuse commission of inquiry on Friday, Eve said she was “really, really worried” – especially since Norman’s father had died by suicide while unwell with bipolar.

“I knew that without the medication, he would start to unravel, that he wouldn’t be coping,” she said.

But every time Eve rang up and complained, Norman was forced to endure “repercussions”.

The staff spoke to her “smugly”, telling her they’d place her son in a little observation cell for “three minutes” to make sure he wouldn’t kill himself.

She told the inquiry she felt the staff weren’t concerned about her son’s welfare – but instead wanted to do everything in-house and “didn’t want anyone interfering with their thing”.

“Their duty of care was really lacking,” she said.

“There was no way of getting information about your child.”

Eve also said every time she visited her son, he was “bastardised” with gruelling cavity searches afterwards.

Eve tried to get help – contacting a GP and an opposition politician to speak to Ashley on her behalf, and asking the Children’s Commissioner for help, but she got nowhere.

“I spent most of my nights sitting up, trying figure out ways to help my child,” she said.

“Because he was being punished every time I made a complaint, he wouldn’t tell me anything anymore.

“It formed a big wedge between us, and all of a sudden he didn’t want me to visit anymore.”

Eve said Norman came out “angry and worse than when he went in”.

“He was savable. He was a child that still could have been turned around and had a future, but they changed that and his future’s been pretty awful,” she said.

“He wasn’t the same person, he’d been through so much trauma. It’s like throwing a child into war.

“It’s like you put someone in a jungle and they’ve got to survive, they’ll find a way to survive, but he came out a different person.”

Eve said Norman was at Ashley when 18-year-old Craig Sullivan – who had been in a car accident – died after not receiving medical treatment.

She said her son had watched the guards make the boy clean up his vomit from the floor only to die hours later.

“He did listen to his friend die overnight. That’s never left him,” she said.

“Once he was dead, life just went on as normal. Nothing changed in there, no-one was held accountable.

“The fact that this young child had begged for medical help and they’d watched him die, it confirmed my suspicions that their inadequacy of treatment for children was absolutely astounding.

“I had hoped his death might have opened up some eyes, but it didn’t seem to.”

Eve said the staff didn't seem to feel guilty about being so hard-hearted about failing to get medical help for a child who would die within hours.

She said she didn’t disagree that her child needed to be detained after committing a crime.

“However he didn’t deserve to have violence perpetrated on him, he didn’t deserve to see friends die, and he didn’t deserve to be bastardised.”

* Names changed to protect identity

Criminologist says youth detention should be knocked down immediately

The bricks and mortar of the Ashley Youth Detention Centre should be “razed to the ground”, a leading Tasmanian criminologist says.

Robert White, giving evidence to the child sexual abuse commission of inquiry on Thursday, said he “wouldn’t wait” if given the chance to reform Tasmania’s youth justice system.

“I would raze Ashley to the ground – I would destroy the physical structure tomorrow,” he said.

“And (I’d) transfer the children to other places – secure houses, but I would certainly knock it down.

“Make it a house. And rather than isolating and segregating children who are in trouble and who are troublesome, we need to surround them with mentors and support.”

Professor White said Tasmania needed to rethink its philosophy of juvenile justice.

He described the layout of Ashley as “awful” – “it’s a very cold and imposing kind of place”.

“It’s physically unattractive and oppressive,” Professor White said.

He said one expert, who he visited Ashley with, said it was the “worst institution he’d seen”.

Professor White also said it was a “misnomer” to give Ashley’s guards the title of “youth worker”.

“There was nothing innovative or progressive about the roles of the youth worker.”

Professor White said he’d gone into Ashley following the 2010 death in custody of 18-year-old Craig Sullivan.

“The specific conditions were horrendous,” he said.

“There is absolutely no excuse why this event should have happened.”

He said the staff came up with “rationale and reasons” for why the death happened, but no-one took accountability or responsibility, either as individuals or as an institution.

He also said the tone of staff was that “this is how we do stuff around here”, transferring responsibility to the young person who died because “they said they were okay”.

“The vibe in this case was just that they didn’t care. The lack of empathy … I was astonished and appalled.”

Professor White also slammed what he said was a lack of professionalism at Ashley.

‘Form of torture’: Detention centre accused of violating children’s rights

ASHLEY Youth Detention Centre has breached both the United Nations’ torture convention, and its convention on the rights of the child, Tasmania’s former Commissioner for Children says.

Mark Morrissey, giving evidence via video link to the child sexual abuse commission of inquiry on Thursday, described the use of isolation at the facility as a “form of torture”.

He said young people were often locked up in their cells for a week or two alone, often due to staff shortages.

“For a young person to be locked in their room, in my view, that does constitute a form of torture,” he said.

He said the facility also breached children’s rights because of failure to provide healthcare for their development damage, and not giving them the ability to make complaints about their treatment.

“I believe they have a right to adequate care and not be put in the situation where they’re further damaged. That’s an example of one of the breach of rights,” he said.

Mr Morrissey said most, if not all the children that entered Ashley, had a background of trauma or developmental disorders.

He said during his time as Children’s Commissioner, a “complaints box” was installed at Ashley – which he said was “absolutely misguided”.

Mr Morrissey said putting the complaints box in public view, and in an environment where many of the children were illiterate, was “never going to work”.

He said in situations where children complained about certain staff members, the complaints went straight to the staff member in question.

“I think it was probably well-meaning by management but absolutely misguided,” he said.

Mr Morrissey also noted that when new staff members came into Ashley with new ideas, they were “often overwhelmed” with the existing, longstanding culture, which had a community that “accepted the status quo”.

‘Treated like s--t’: Former Ashley detainees detail abuse

WARREN* was raped more than 20 times by a singular guard during his time detained at Ashley.

And he was sexually abused by a trio of guards over 50 occasions, who’d withhold his medication until he touched himself or performed oral sex upon them.

The guards also restrained him by pinning his arms behind his back until they felt they would break.

One guard rammed his head into a wall, fully aware that Warren had a previous head injury where he’d fractured the front of his skull.

But he never told anyone and never made a complaint, with the guards in question threatening to burn down his mother’s house if he did so.

“They said no-one would believe me anyway because I was just a little criminal,” Warren said in a statement read to the commission of inquiry on Thursday.

His story started at age three, when physically abused by his mother, Warren was placed into care.

“I kept stealing from them in the hopes I would be sent home,” he said.

Ultimately, he was sent to Ashley at age 13, where he was subjected to “degrading and abusive” strip searches by employees that sexually abused him.

“I never made a complaint,” he said.

“The process of making a complaint was to write it down and give it to the workers.

“They would make your life hell and make you suffer more. Because of this, no-one made complaints.”

Simon* also gave evidence to the commission, via video link, on Thursday.

He said he was “treated like s--t” at the centre from when he first went in at age 10.

“There used to be a really old guard and he used to sit there and watch you shower. What the hell? He got called a dirty old dog for doing that. That was his nickname,” Simon said.

“I used to complain about it but no-one believes you.”

He said if the kids at Ashley did anything to “slip up” – like not go to bed on time or not listen to the guards – “they’d smash you up”.

He spoke about his friend Craig Sullivan, who died at Ashley in 2010.

He’d been detained in the aftermath of a car accident, and wasn’t referred for medical assistance.

“He was complaining about his head,” Simon said.

“It brings a tear to my eye now, it wasn’t nice.”

Simon also spoke about the times he spent in isolation, in cell 9, in freezing cold conditions as “punishment”

At one stage, Simon estimated he spent two-and-a-half weeks in that cell, with nothing more than a horse blanket.

“They’d bring you food once a day,” he said.

“It was freezing, I’m telling you it was freezing, it felt like it was snowing.”

* Names changed to protect identity.

If you or a loved one is struggling, further support is available:

- Lifeline Australia – 13 11 14

- Beyond Blue – 1300 22 46 36

- Rural Alive and Well – 1300 4357 6283

- Kids Helpline – 1800 551 800

‘Violence, brutality’: Child sexual abuse inquiry examines youth detention

THERE was no one particular monster that infiltrated the walls of the Ashley Youth Detention Centre – because Ashley itself was the monster.

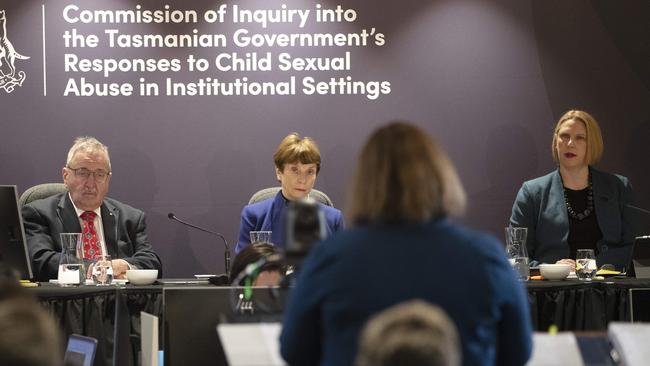

Those powerful words were delivered on Thursday in an opening address to Tasmania’s child sexual abuse commission of inquiry, which has recommenced hearings in Hobart.

Rachel Ellyard, counsel assisting the commission, said over previous months, the inquiry had heard about how “predators” and “monsters” had managed to enter state government facilities to sexually abuse children.

“(This) invites the possibility of a finding that Ashley the institution is itself abusive,” she told the trio of commissioners.

“It has defeated every attempt thus far that has been made to make it safer.

“Here you might find that it’s Ashley that’s the monster.”

Ms Ellyard said the reason Ashley had perpetuated itself as “damaging and toxic facility” might be found in its origins – with the centre previously having been a boys’ home.

“Practices in the former Ashley boys’ home were punitive and violent, and some children were physically and sexually abused,” she said.

Ms Ellyard said a number of staff members were transferred from the boys’ home to the detention centre, and remained working there for many years.

“Some of those still work at Ashley, or did until very recently,” she said.

Because of a lack of staff, some employees from the adult Risdon Prison were brought in to assist, which “cultivated an environment of violence and brutality”.

Ms Ellyard said the staff weren’t trained in youth work or the complex needs that children at Ashley came with, especially given most of them came from traumatic backgrounds.

She also said staff were traditionally recruited from Deloraine and the nearby township, with the centre staying open because it was a “major employer in the area” – not because it was fit for purpose.

“Staff at Ashley have always been underqualified and under-trained for the complex and difficult work that they are required to do,” she said.

She said since the early days of Ashley, it had “fallen short” of community expectations and did not rehabilitate children.

“Children are not safe, children are not respected, and children are not treated in a way the community would expect,” she said.

“We expect the Tasmanian community will be horrified by the evidence that is to be called over the coming days.”

Ms Ellyard said while the evidence to be canvassed in the coming weeks would be disturbing – it wasn’t new.

“There will be evidence that successive governments have failed to achieve meaningful change,” she said.

“None of the evidence should come as a surprise to the government.

“It appears from the materials we’ve received that at a government level, there’s been no action taken.”

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘It’s like throwing a child into war’: Mother says her son was changed by the Ashley Youth Detention Centre