Reporter PAUL TOOHEY and photographer GARY RAMAGE find a white minority in South Africa being murdered and tortured off their farms — as their families in Australia watch on helpless.

IN KIMBERLEY, where the diamonds are dug, Rikkie Alsemgeest had a funny feeling on the afternoon of January 23. Normally she stays at her own home in town on weeknights and only overnights on the farm of her 86-year-old partner, Piet Els, on weekends.

Something told her to stay with Piet that Tuesday night.

At first, they first thought the noises were the farm cats. Then four black men wearing hoodies and holding torches broke through to their bedroom. Rikkie is 67. Her pyjama pants were stripped from her and she was digitally raped as Piet was belted with an iron bar.

Unlike many white farmers, Piet hadn’t installed electric fences and guard dogs on his 400ha beef farm.

HAVE YOUR SAY: Should Australia take white South African farmers as refugees?

He’d been a friend of Nelson Mandela and, as a wealthy man, was known as someone black people could ring for help. He thought reputation was his protection.

But there is little defence for white South African farmers, rich or poor.

They are being targeted in ruthless opportunistic crimes and what appears to be an orchestrated terror campaign — so much so that some of their families in Australia believe they should be treated as refugees.

The violence that accompanies farm attacks — which hit a record 400-plus last year, with one or two farmers killed every week — is so abnormally cruel that many whites feel certain they are being sent a message to leave the land.

Holes drilled through the feet of elderly women. People burned alive. Women raped and bashed. Men shot dead in front of their wives and children. Rikkie and Piet were both burned with a household iron.

“I said, ‘I will show you where the safe is,’” said Rikkie.

“They hit me on the side of my head. We went to the room where the study is. Piet’s eye was all swollen. He was so confused and couldn’t get the code in. Every time he put in a number they hit him again. They hit me across my legs with a steel pipe, and across my chest.

“Then they tied me to a chair and came with a steam iron they found in the kitchen and burned me here (on her inside knee). But Piet they burned on his back in three or four places and burned on the back of his leg. They stripped off his skin.”

When we spoke to Rikkie, the attack was fresh and Piet was in ICU. Like others, she talked about the event like it had happened to someone else. She was strong, but traumatised.

Piet was so confused by raining blows he couldn’t remember the safe’s combination. Rikkie didn’t know the numbers and told the men where they could find a grinder.

“And they did. I thought Piet was dead because he was lying on the floor. They put a cloth in my face and tied me to the chair. They stripped off my top. I was naked. They put some tape over my face and eyes. They took my breast and twisted, humiliating me, not saying a word.”

They cut open the safe and took jewellery. Several of the men were caught and are being prosecuted. But in most farm attacks, no one is arrested.

Rikkie is a sophisticated woman who understands the wrongs of Apartheid. Both she and her partner wanted to be part of Mandela’s dream. Even now, she does not want to leave.

“This will not run me out of Kimberley,” she says. “Why not? Because then they win. A lot of South Africans went to Australia, New Zealand and the UK. It hasn’t helped this country.”

FIGHT OR FLIGHT

THEY LEFT when the writing was on the wall for Apartheid, without giving the new South Africa a chance.

Or they tried but found the violence too much. They came to Sydney, Perth, Melbourne, Adelaide and the Queensland coast — 200,000-plus South African-born citizens, and 40,000 Zimbabweans.

Australia is the most desired destination. It looks and feels like home and the outdoors “braai” or barbecue lifestyle is not so different.

South Africans are different to others who come to Australia seeking a new life. They are mostly white, have money, and those who are not too settled with Australian-born kids would go home in a heartbeat if things improved.

For those who stayed behind, stubbornly refusing to be chased off, or because they cannot meet migration requirements due to age, skills or money, they are now under assault.

Erns Hattingh, 34, and his wife Aninke came to Sydney a year ago, sick of the violence. Erns’ family sold the farm four years ago for fear of attack. He and Aninke took a decision to migrate as skilled workers, which they were able to do because of their age.

They both had to leave parents behind. A “parental” visa costs around $100,000 — that’s just one side of the family. The family doesn’t have the money. “I think they should qualify for visas as refugees,” Erns says.

“The brutality is almost unheard of. There should be a special allowance for people who are the victims of these crimes.”

The new South African president Cyril Ramaphosa’s ruling African National Congress a fortnight ago joined with the socialist Economic Freedom Fighters to overwhelmingly pass a motion to expropriate land “taken under colonialism and apartheid” without paying compensation.

EFF leader Julius Malema said last week the mayor of Port Elizabeth should be removed because he is white. “We are cutting the throat of whiteness,” Malema said.

The organisation Black Land First — the BLF —last year said there were a record 20,000 farms on sale but warned buyers “not to buy stolen property. All the land in white hands is stolen property.”

It is starting to look like when Robert Mugabe’s thugs overran white farms in Zimbabwe.

CCTV images from a December 2015 farm attack shows armed raiders with military-style phone-jamming equipment — the type used by Coalition soldiers in Afghanistan to block insurgents making calls to set off roadside IEDs.

It is thought the jammer was used to stop the farmer calling for help; but this use of military-grade equipment fuels fears farm attacks has high-level support.

Whites have always been a minority in South Africa, as oppressors and now victims. Whether Afrikaans, British-descendant or otherwise, they are now grouped as Boer, or the plural, Boere, which means Afrikaans’ farmer but is now used against all whites as an insult.

The old anti-Apartheid song which carries the words “Shoot the Boer” is now classified hate speech but continues to be chanted.

The white minority meets the internationally accepted criteria of refugee. But they attract little sympathy. There’s a view that they had this coming — payback for Apartheid.

A DAMAGED LAND

BERDUS HENRICO is nursing three fresh bullet wounds — two through his shoulder and one through his face that came out the back of his neck. And yes, he says. It hurts.

It was dusk, three weeks ago, on a game park in the Limpopo province when Berdus, 39, and his partner Estelle Nieuwenhuys, 51, were raided.

Berdus had no time to go for his rifle and charged at two men holding a knife and a screwdriver. A third attacker who was on lookout outside rushed in and unloaded at Berdus. Estelle was grazed by a bullet and both were tied up with fencing wire.

“This is normal in South Africa to be attacked on a farm,” says Berdus. “They took my hunting gun, my shotgun, two cell phones, our DVD player, our TV.” They did not know the attackers. Estelle was praying, out loud, begging them to stop.

“They wanted him dead,” says Estelle, who believes the attackers’ pistol jammed. She says they put Berdus’ guns to his head but the shotgun had its firing pin removed and Berdus’ hunting rifle has a complex mechanism only he can use. He was then struck with the back of the pistol.

Berdus has guided numerous Australians through his park; he has a cousin in Townsville. He knows us, but knows his own country less and less.

“They want money and they want guns,” says Berdus. And political motive? “Yes. They want the people off the land so as they can go on like they want to. They want it here like it was in Zimbabwe a few years ago when they chased all the whites out and let it go to the ground.”

News Corp Australia met Berdus and Estelle through AfriForum, a group that was set up to draw attention to the farmers’ plight.

With 206,000 paid members, AfriForum runs an intelligence bureau that monitors attacks, sends alerts, runs community safety advice, patrols problem areas, assists with victim trauma and undertakes road repairs in remote areas following the US “broken windows” theory that places left to decay become high-crime areas.

“There is something warlike in the country,” says Ian Cameron, head of AfriForum Community Safety. “This country is damaged. We are psychologically damaged.”

He says while his government views farm attacks as “normal” crime, AfriForum disagrees. “The cruelty that goes with farm attacks is disproportionate compared to other crime,” Cameron says. “An urban crime might last 10 minutes, but (on farms) people can be tortured for up to nine hours.”

AfriForum documented a record 404 farm attacks across 2017, four times the number recorded a decade ago. The 2018 figures look set to easily outstrip last year’s numbers.

Trying to work with police and government to raise awareness, AfriForum has come under attack from black groups who see them as racist; and hard-right white separatists who think they’re too liberal.

Mostly, they want the government to speak up. “If we see a white farmer being tortured, being burned with torches or clothing irons, gang-raped, we don’t see any focus on these cruel crimes,” Cameron says.

In 2016, two white farmers assaulted a young black man and shoved him in a coffin, threatening him to kill him for supposedly trying to steal from their land. The farmers were sentenced last year to 14 and 11 years each.

The macabre case was a huge story in the black-dominated media, and a nightmare for AfriForum’s awareness program. “It was a massive setback,” says Cameron.

‘JUST LEAVE MY MUMMY ALONE’

APPLICATIONS by white South Africans seeking Australia’s protection generally fail. The view of the Refugee Review Tribunal is that more blacks are killed in South Africa than whites, therefore whites cannot claim greater degree of persecution.

In the last five years, 12 South African-born persons have been granted a humanitarian visa by the Australian government — but there is no breakdown whether they are black or white.

The RRT recently rejected the case of an elderly white farmer whose wife and three others were notoriously burned to death in 1999. He lives in Queensland and cannot bear the idea of going home.

However, the RRT did recommend the Minister for Border Protection make an exception for this damaged man. The lawyer representing him was anxious his client not be named, fearing there would be a backlash was it known the Australian government had helped a white South African.

South African-born Brisbane migration lawyer Hendrik de Korte says Australian tribunals and ASIO have looked closely at the case for white South African refugees.

“To say, ‘I am being persecuted,’ is where it all falls flat,” he says. “The problem is everyone is under attack. If you’re a black man in Jo’burg, you are at greater risk of carjacking that any other group.”

Mariandra Heunis, 34, has sometimes thought of leaving, but how? She’s had to start life again after September 3, 2016, when she and her husband Johann, 43, were raided on their small chicken holding out of Pretoria. They had three young daughters and Mariandra was 36 weeks’ pregnant with their first son.

She and husband were asleep on the lounge with their oldest daughter, then aged six, beside them. They considered their property, surrounded by electric fences and dogs, safe. Sometime after midnight, Mariandra was woken by a noise the police would explain was the cocking of revolver.

“Two of them were at my feet with a gun pointed at me. My husband woke up. They demanded money. In the screaming and aggression my daughter woke up, hysterical. One guy said (of his accomplice), ‘This guy is a killer and he is here to kill you all.’”

Johann said they could take anything. “And then the shots rang out,” says Mariandra. “I didn’t know where to go. I can’t protect my husband, my daughter and my unborn baby. I saw Johann had taken a shot — I saw the blood. I didn’t realise they’d already shot him five times.

“They pulled me up off the couch and said to come downstairs. I immediately thought of rape. I pulled back and my little girl put up her hand and said, ‘I’ve got a piggy bank. You can take my money. Just leave my mummy alone.’

“And at that point Johann got up one last time and said, ‘Please.’ And the one guy said, ‘Just kill him, brother.’ And they shot him between the eyes in front of us.”

Mariandra’s other two smaller daughters were hiding in their room downstairs. The men asked where they were, which suggested — as in many other farm attacks — they had been observing the family. To this day, she cannot explain how the attackers subdued their dogs.

Their phones and the car keys were taken — but not the car. Mariandra wasn’t sure if the men were coming back or not. She found the spare keys and sped away with the headlights off. Her new life began.

“I had to have a funeral for my husband and the father of my children, and I had to give birth five days later. Saying goodbye and saying hello. I had to be joyful of this little life. Our first son. And I couldn’t be because I was so sad.”

They’ve never been back to the farm. Mieke, now 7, the girl who offered to piggy bank, is being treated with antidepressants. Memories are less clear for Mischa, 6, and Majandre, 3. Strangely, AJ, the one-year-old son, experiences emotional “triggers”, even though he was not born when his father was executed.

“My kids aren’t scared of monsters,” she says. “They’re scared of people.”

Mariandra, who now works in a funeral home helping people through grief, says her attack wasn’t about theft. “If you’re there to steal, you take stuff. You don’t torture people, you don’t shoot someone six times.”

The government’s Black Economic Empowerment policy sees “previously disadvantaged” people fast-tracked into jobs without proper training. That includes the police force. She identified one of the attackers in a line-up but he has been freed.

RAPE OR DEATH

IN THE OFFICES of AfriForum in Pretoria where she works as a procurement officer, Hilda van der Merwe, 56, has photos of four of her six grandchildren on the wall of her workstation. They live in Perth.

Hilda is just back from a six-week visit to Australia, visiting a son, a daughter and the grandkids. While she was away, her sister’s brother-in-law was murdered on a small holding.

That’s how it is in South Africa. Every day, 52 people are murdered — one of the top 10 homicide rates in the world. Hilda’s daughter, Maryke Boshoff, 39, lives in WA with her husband and two children. “We worry for the whole family back in South Africa. We pray for them every day,” she says.

“Since we’ve left South Africa 11 years ago, my husband’s godparents were brutally murdered in a security complex. People don’t have a life there and I can’t see it getting any better.”

Maryke’s neighbours were slaughtered. Her brother, who also now lives in Australia, was carjacked and tied to a tree in a township. “I love Australia,” she says. “It’s like South Africa used to be. I’m talking about the climate, the housing, how it used to be safe, even post-Apartheid.”

Vicky Strauss, 32, who lives on a farm in KwaZulu-Natal with her husband and two children, hopes to get to Australia or New Zealand. “It’s not really for financial reasons,” she says. “It’s about the kids. I know people who have gone and they say it’s just so nice not to worry when you hear your dog bark.”

What happened to her mother, Hannetjie Ludik, 56, on a small holding outside Pretoria on December 21 has hastened her desire to leave.

Hannetjie and her husband Callie had lost their jobs and had just moved to the small rural outpost, unaware of its shocking history of farm attacks. Three men came in the night, with guns. Callie was bound and they went through the property — but there was nothing of value to steal. Not even food.

One man took Hannetjie aside: “He said to me, ‘You want sex?’ And I said, ‘If I refuse?’ He said, ‘Then I will have to shoot you.’ I decided to live, for me and my husband. I decided, ‘Well, you must do what you want to do.’”

Three men took turns raping Hannetjie. They wandered off, with matter-of-fact goodbyes. They have not been found and Hannetjie is unsure whether she is HIV positive.

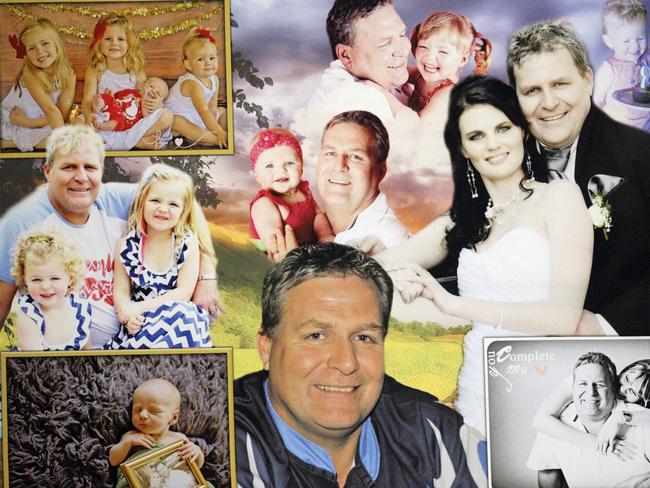

Bernadette Hall, 50, lost her husband David, at the age of 48, in 2012. They ran a milking property 70km south of Johannesburg and were doing the morning shift when Bernadette saw five men coming towards them through a corn field, one holding a gun.

David pushed Bernadette into a shed. Through a crack in the door she saw them kicking and hitting him. “Next minute when I opened the door I saw David standing on his knees,” she says. “One guy just shot him.” In the heart. He fell face forward. “He couldn’t fight any more.”

Bernadette was hogtied in the garage and they stole their bakkie — the ute. Three men were arrested and she identified two of them in a police line-up. In court, her evidence on which attacker held the gun and which held the machete was back-to-front. They both walked. They still live nearby.

She believes this was a revenge after David had told a worker he could not have his girlfriend and aunt living on the farm.

Last March, one of Bernadette’s elderly female farming neighbours, Nicci Simpson, 60, had her foot run through with an electric drill by men torturing her for her safe’s combination; and in October, another neighbour, Willem Barnard, was shot dead for no known reason.

“I don’t say every single one (of the attacks) is political but it has become more political now,” she says. “When you listen to what politicians say about the land grabs and giving it back to black farmers, the instances become more brutal.”

paul.toohey@news.com.au

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

‘You can’t live in an approval’: Report card on housing crisis

Industry leaders have issued an eyebrow-raising report card on NSW’s housing delivery, with experts warning the state will fall 25,000 homes short of federal targets despite major reforms.