THE twin Telecom phone boxes took coins and Sharron Phillips didn’t have any. It had been a long night and she was still stranded. She’d walked up the road looking for a phone. Walked back to her car. Stood, alone, in the dark, waiting for her boyfriend to arrive.

A couple of people had called out to her. Did she need help? Was she OK? Someone had offered her a lift but Sharron wasn’t stupid. She wasn’t getting into a stranger’s car late at night.

She’d called Martin, her new man, about 45 minutes earlier but he’d been half asleep when he’d answered. She’d tried to describe the service station. It was small, a Shell. On Ipswich Rd.

“Wait there,” he’d told her. “I’ll find you.” But he hadn’t found her. And as the clock hit midnight, and May 8 became May 9, Sharron was back at the phone box.

She spoke to the operator and asked to reverse the charges. Gave them her boyfriend’s number again. The flatmate answered. Martin had left already. Should have been there by now. She hung up the phone.

The brightly lit phone boxes sat on their concrete bases like twin beacons outside the Wacol snack bar and convenience store. Next door was the equally well-lit Shell service station, a squat, white building with three pumps under a protruding roof. Passengers walking to and from the Wacol train station would pass by here. Cars driving along busy Ipswich Rd would scan their headlights along here.

It was bright, visible. But not so the dirt track running behind those shops. There, it was dark. There, it was cut off from the road, from passing traffic, from people walking by.

There, a taxi driver manoeuvred his cab into its usual spot, ready for the next driver to collect.

There, nobody would hear a sound.

BOB Phillips was a big man, strong and broad-chested with a quick temper. He was rough, a truckie who married his bride when she was 14 and he seven years her senior. Together they’d have nine children. The kids grew up feisty, like Bob, and protective, like Bob. You didn’t take on one of the Phillips kids without taking them all on.

One of the younger kids, Merlesa, was 10 when she came off her bike. She was taken to hospital with a nasty cut and left with a golden staph infection. It made her sick and destroyed her knee. She’d spend the next five years in and out of hospital – and the rest of her life unable to walk properly. A year or two after the accident, Merlesa was back in hospital. She wasn’t eating. Anorexia, they murmured.

“You guys aren’t doing anything,” Bob told the doctors, and dragged his daughter out of there.

Back at the family’s home at Riverview, a suburb of Ipswich, he sat Merlesa down and demanded she eat. He was at it every day. The burly truck driver and his little girl. A plate of food and an immovable obstacle, watching her until she’d finished every bite. He’d force-feed her if he had to. Tough love all the way.

By the mid-1980s, the older kids were starting to marry and move out. Sharron, who was in the middle, had just rented a flat in the nearby suburb of Archerfield. She had a job at a local fruit and veg store and a car, which she’d saved for ages to buy.

Sharron was proud of her little unit. After the chaos of the Phillips’s home, it was a sanctuary. She’d arranged her polished pine lounge suite around a large crocheted rug. Knick-knacks sat on small side tables. Plants decorated corners, benches and walls. They grew from baskets on the floor. She bought an expensive stereo and television. Art for the walls. She put photographs of her family everywhere. Her younger siblings loved her unit and Sharron told them they could take turns spending the weekend.

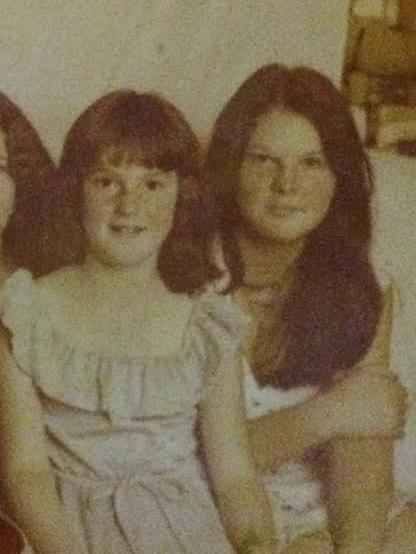

The family called her Big Bird. She was tall – just under 183cm – and solid. Like most of the Phillips clan, Sharron was rowdy, brash and feisty. She laughed all the time, laughed at everything. People were drawn to her. She had a heap of friends and just as many boyfriends. She’d been engaged for a while – he was her best friend’s brother. And when it didn’t work out, she’d stayed friends with his family anyway.

She loved to dance, and at 20, she’d head into Brisbane to hit the discos with her friends. Sharron was a striking girl. She bought beautiful clothes and knew how to style her long, dark, wavy hair. She knew how to use makeup, how to hold herself.

It was a Saturday night in May when she met Martin Balazs. He was shy, but he seemed nice and lived only a few minutes from her place at Archerfield. They agreed to go out that Monday, double-dating with another couple. A picnic in Toowoomba. At the end of the day they were arranging another date. This time it would be just the two of them. Friday night. She was excited.

BACK at work, Sharron whispered in the ear of her friend Samantha Dalzell. There was a new man on the scene. They’d go shopping Thursday night, the girls decided. Sharron would buy some fancy lingerie for her date. They were back at the Archerfield flat by the time the shops closed and Sharron made them coffee. They sat at her table, jostling for space with a well-tended fern. But soon it was time for Sharron to drive her younger friend home. They had work the next day.

She waved Samantha off at her Redbank Plains home and headed the car back towards Archerfield, a 30-minute drive. She’d need petrol, but it was late. Sharron was good with her money but she’d much rather spend her hard-earned on a dress than a tank of fuel. She was notorious for throwing in a couple of bucks’ worth instead of filling up.

She was somewhere on Ipswich Rd when her Datsun choked to a halt. She looked around. There had to be a phone somewhere.

MEMORIES fade over time and 30 years is longenough to wipe many of them away. But some things you never forget. Merlesa was 14 when a phone call to the Phillips’s Riverview home changed everything. They couldn’t see it then, but a crack began to open and spread through their family that day. A fissure, a fracture. It would widen over time into a great chasm of hate.

Bob Phillips put down the phone. It was Sharron’s work. She hadn’t turned up that morning.

“I remember the police coming over the following day and Mum and Dad sitting down with them to report Sharron missing,” Merlesa says. “They were sitting at the kitchen table but I couldn’t understand what was going on. It was a lot to take in.”

Bob and Dawn were beside themselves. Sharron would not have run off. She had her flat, her car, her friends. She was a reliable worker. “Sharron will be fine,” they told the younger ones. “We’ll find her.”

But Bob, their big, tough-love father, was crying. And Dawn was barely holding on. “What are we going to do, Bobby?” she’d wail.

They were going to bloody look for her, that’s what.

HE drove the cops crazy, dogging their every step, getting up them for making mistakes. They’d been to her flat the day she’d disappeared. Lisa, one of the older kids, had found Martin’s phone number in Sharron’s address book. Bob called him, asked him if Sharron was with him, if he’d heard from her.

“No,” Martin said. He thought it was one of his mates having him on. He’d gone to pick her up when she’d called but when he arrived at the big, brightly lit service station on Ipswich Rd, there’d been no sign of her.

He’d kept looking, thinking maybe he’d gone to the wrong one, and ended up with a flat tyre. By the time he’d found her car – near a second, smaller service station 2km down the road – she wasn’t there.

She’d probably called someone else, he thought. Maybe she was mad at him. On Friday, he’d gone out in the rain and bought a bunch of flowers to give her on their date that night. A peace offering. He’d tried to hide them from his flatmates but now a gruff voice on the phone was asking if he knew where Sharron was. A prank, he decided, and played dumb. By Saturday, another dreary, wet day, he knew he’d been wrong.

Sharron’s brother Darren had called, asked him again. Convinced him that Sharron was really gone. The police came after that. And the gossip and the stares. Everyone always suspected the boyfriend.

By the time the police cadets started their careful line search of the roadside, it had been raining for two days. Sharron’s family had been through her flat, through her car, touching things, desperately searching for clues as to her whereabouts.

Police, who’d questioned Martin Balazs, went looking for proof that she’d called him from the big roadhouse at Gailes – a decent walk from where her car had stalled. Nobody had seen her. They’d seen Martin, though.

Sharron’s picture was released to the media and journalists picked up the story. They arrived at the Phillips’s house to find Bob and Dawn barely holding themselves together. But they knew the value of having Sharron’s picture in the paper, so they talked to anyone who came.

“I can stay awake for 60 hours but I just can’t handle this,” the rough-talking truckie said. “We were very close.” He cried as he spoke. His wife tried to comfort him. “We just hope she has run away, although it is right out of character,” Bob said. But they knew. Sharron hadn’t run away.

Then, on May 13, after days of searching, Courier-Mail reporter Ken Blanch revealed he’d been doing his own investigating. Police had been looking in the wrong place. Sharron had never been at the Gailes roadhouse.

Blanch had walked the road, trying to get a handle on Sharron’s last movements. Her car had broken down near the Wacol Migrant Centre. There was no phone there at that time of night.

There would have been one at the army barracks, but a group of soldiers who had been celebrating their graduation that night denied having seen her.

A few hundred metres from her car was a small Shell garage. Next to it, just in from the corner, on Wacol Station Rd, was the snack bar and convenience store. And next to that were the two Telecom phone boxes. It made no sense, Blanch thought, for Sharron to have walked past these phones to the Gailes roadhouse 2km on.

He went into the snack bar and spoke to the man behind the counter, Albert Baumgartner. Did he know anything about the missing girl? Had anybody seen her that Thursday night?

Sharron’s face had been on the front page of the paper the day before. One of the regulars had told the store owner he’d seen her while picking up his son from the train station. His son had even spoken to her. Sharron had mentioned running out of petrol. She was waiting for a friend to collect her.

Other mistakes had been made too. Bob had driven his daughter’s car home. He’d later claim police told him to get it off the side of the road. As the investigation moved from a missing persons case to something worse, police told him to bring it back. A peg had been left in its place and at some point, detectives realised the marker was 60m out.

Once again, they’d been searching in the wrong place.

SHARRON had been gone for a week when they found them. With the position of Sharron’s abandoned car now properly identified, police were again conducting line searches along Ipswich Rd. In a drainage ditch beside the road, an officer spotted a small Glomesh purse and a pair of shoes. They’d searched that spot already. Had they missed them? Or had somebody driven back there, sometime in the past week, and left them for police to find?

“Those things were not in the ditch the day after Sharron disappeared,” Bob insisted. “I know, because I fell into the bloody thing.”

Back at the Phillips house, things were falling apart. Bob and Dawn were working hard at keeping the little ones away from everything that was happening but it had been difficult. Police were in and out of the house. The phone rang and rang. Well-wishers, busybodies, psychics. Journalists, photographers and cameramen came by.

Merlesa was the artist of the family and Bob and Dawn had her making posters they could give out. A photographer snapped a picture of her working away one day. Bob and Dawn weren’t home at the time and would never have agreed to the young ones being photographed. “Dad flipped his lid when he found out,” Merlesa says.

Bob continued to clash with police. He’d get a call from someone with information and he’d be off searching the bush with a shovel and one of the boys. On Thursday nights, they’d head back to Ipswich Rd where they’d wave photographs of Sharron at motorists, hoping to catch someone who regularly drove by who’d seen her walking the street. Police ordered them off the road more than once, worried they’d be hit by a car. But the practice of returning to a scene at the same time on the same weekday to look for witnesses is now a common investigation technique.

Despite the early mistakes, police were doing everything they could. They took hundreds of statements, followed countless leads. But as the days went by, answers seemed further and further away.

THE younger kids were kept away from school for weeks, with Dawn terrified of having them out of her sight. When they did go back, all eyes turned to stare.

“Everybody knew,” Merlesa says. “Most of the kids were fine, they were really nice. But 14-year-old boys can say some nasty shit.” They’d pass her in the yard, sneering about the most terrible tragedy a family could endure. “Your sister’s dead!” they’d say.

With the older kids out on their own, and Bob and Dawn spending their days searching for their daughter, the running of the household was left to Merlesa and little sister Natasha. “We did the cooking, we did the washing, made sure Mum was fed and Dad didn’t have to worry about anything while he was out searching,” she says.

“We were getting calls constantly from people who had seen her or knew where her body was. Every time it happened, Dad would be out looking again. He tried to keep it hidden but we knew what he was doing.”

Merlesa, Natasha and Matthew – the three youngest – were smothered by parents who had been to hell and back. Their childhood became entirely about Sharron. The freedoms the older kids had experienced became a thing of the past. Children were safer at home, where Dawn could see them. The loss of Sharron, the lack of answers, hit Dawn hard and her mental health suffered. She became fragile. Sharron’s case was so well-known that Bob and Dawn were easily recognised wherever they went. “Every once in a while, Mum would want to go out and do something normal, like walk around a shopping centre,” Merlesa says. “My sister and I had to guard her because people would come up and say ‘oh, you’re Sharron’s mother, I’m so sorry’.”

Dawn had started writing things down, a scattered record of troubled thoughts. She used scraps of paper, exercise books, and later, a journal. “So many versions of what happened to Sharron. The latest is she was hit by a drunk driver and died on the back seat of his car,” she wrote months after her daughter disappeared. “So many stories; I wonder if one of them is right? I pray one day we will know the truth, that she will be found … ”

Other entries showed her despair, her fragility. “It would be so easy never to see or speak to other people. Maybe one day I will retreat into myself. It scares me a bit. I’m not a bit brave, I’m just so afraid of the future,” she wrote. “Sometimes I wish I could just go to sleep and never wake up again, but I couldn’t leave Bob in such pain alone with the kids to bring up. I love them all so very much. What kind of a world is it going to be for them in the future? Matthew is asking who is his sister’s killer. It hurts so much to hear such words out of a seven-year-old about his own sister. So many cruel words now that he had never had to hear before.”

It took her two years to break. “She lashed out more than anything,” Merlesa says. “Later, she’d be embarrassed by it. She needed lots of care and attention. Sometimes she would just sleep for days. I think she thought, there’s nothing left for me to do any more, I’m just going to sleep. It was hurtful for the younger ones. We were still there.”

Christmas in the Phillips house, once a rowdy celebration, was now a chore to get through. The cracks that started to open when Sharron disappeared were widening, and the older kids fell out with their dad.

“It has torn me apart every day to lose Sharron, and then to see you tear each other apart … ” Dawn wrote in 1988. “I can’t side with anyone as I don’t want to lose anyone else. Sharron was one too many to lose. Sharron is not to blame, or any one of you, but whoever took away my daughter also ruined my family and our lives.”

LIFE went on. The endless search for Sharron had depleted the Phillips’s finances. Bob sold his truck to pay the debts. He found an ally in Detective Bob Dallow, the head of homicide. Dallow was a tough-talking, old-school cop. He was equally determined to find Sharron. Dawn had her good days and her bad, but the bad were becoming the norm. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and doctors struggled to find medication that worked.

“She was up and down like a yoyo,” Merlesa says. “She’d turn into this horrible person we didn’t know. It wasn’t her fault. It was the effect of the meds.”

Police explored new leads. Prisoners would tell of fellow inmates bragging about killing Sharron and burying her in the bush. Police would tell Bob and Bob would head out to look for her.

One New Year’s Eve, Merlesa headed into the city for a day of celebration with friends. She’d been given a strict pre-sunset curfew but December 31 trains are unreliable and it was after 10pm when she made her way up the street.

“I remember getting home and that feeling of knowing I was in trouble. I would have been 19 but when you’re a teenager, you want to rebel. That’s what you’re supposed to do,” Merlesa says. “But it was serious to Dad. So many times, I got into trouble.”

There are too many memories, too much sadness, from those years. Dawn being admitted to psychiatric facilities, not recognising the faces of her husband, her children. Lashing out at the people trying to care for her. Merlesa cancelling on a date so she could fill in paperwork to have her mum committed. Dawn crying, not wanting to go. She hated it there. Dawn getting sicker and sicker. Dawn dying in 2010, having never found out what had happened to her daughter. Bob lost without her. Weakening without her.

Sharron had been gone for years by then. Decades. The children had moved away. Half of them hadn’t spoken to Bob in years. Bob got sick. Strokes, falls, heart attacks. And eventually, bowel cancer. He’d stopped looking for her in the end. When he’d been too frail to do it, too weak to physically search. That’s when he’d stopped looking for Sharron.

“Twice I was called and told he was going to die,” Merlesa says. “Whatever fate could throw at him, it had thrown it. I saw my father three days before he died. He was a shell of a man. He wasn’t my dad any more. He was just frozen. He couldn’t walk or talk. But he talked to me with his eyes. He was still in there, in that shell of a body.”

Dallow once considered Bob Phillips a friend. He went to family weddings. He watched Dawn slide from nurturing mother into madness. “My wife Kay felt sorry for Dawn. Dawn turned into a bloody vegetable. Then Dawn started talking, Bobby this, Bobby that, Bobby put Sharron in a box,” he said. “I thought, it could be right.”

It wasn’t a falling out, as such. But Dallow said he began to look at his friend Bob in a different light. He knew Dawn was sick, confused. That she said things that weren’t true. But what if he had done something to his daughter?

When Bob died, Dallow went to his funeral last August and got to talking with some of the older siblings. They hadn’t spoken to their father in years. But they knew all about his fiery temper. Months later, they went public. They wanted police to re-examine their father’s alibi. Dig up the bushland next to the family home. Every television news outlet shot footage of Dallow, joining the Phillips kids in calling for a new investigation.

Police declined. They were happy with Bob’s alibi. And they weren’t going to conduct a major search on a hunch, on a gut feeling. But in dragging their father’s name through the mud, Bob’s kids inadvertently brought about a major breakthrough.

Dallow spends his days in a small shed at the back OF a second-hand bookstore at Ashgrove, in inner-northwest Brisbane. It was here the man found him. “I spoke to the fellow that gave (police) the information first,” he says. “The story he tells sounds genuine. Not only reasonable, but genuine. He might be the biggest liar in the world but he convinced me. After a fair few investigations, you get a feel for it.”

Police had heard hundreds of stories over the years. People confessing. People with wild stories of abduction and murder. This one was just as wild. The man said he needed Dallow’s help to convince police he was telling the truth.

The man’s father had been a cab driver. At the end of his shift, he’d park his cab down the dirt lane behind the shops where Sharron had used the phone. He’d leave it there for another driver to pick up. On these nights, the taxi driver’s son would follow him to the shops, pick up his father, and drive them both home.

“The (taxi driver) wasn’t exactly Mister Nice Guy. He was working for a criminal as well as being a cab driver,” Dallow says.

The son claimed that on the night Sharron disappeared, he was pulled over by police as he followed his father, and fined for a traffic infringement. He pulled in behind the shops about 10 minutes behind his father.

Sharron, he says, was tied up and gagged with tape in the boot of the taxi. He watched as his father pulled her from the boot and walked her to the other car. Dallow believes feisty Sharron would have fought hard if someone attacked her. He believes she would have been dazed, probably from a blow to the head, for her attacker to tie her up.

The son had recognised her. He knew Sharron – not well, but everyone knew the Phillips family in that part of town. He’d asked his father what was going on.

“Don’t you worry about it,” the taxi driver had said.

He loaded Sharron into the boot of the son’s car. The son got in and drove his father to their home.

At the house, the son said he got out and his father got behind the wheel and drove away.

He doesn’t know what happened after that. He did know, from the news reports that followed, that Sharron never made it home. Later, while they were driving through the Ipswich suburb of Carole Park, the taxi driver had pointed to a stormwater drain. That’s where he’d left her body, he’d said.

The taxi driver’s son spoke to Dallow for a long time. He’d been terrified of his father. But now that he was dead, he could no longer live with the guilt of knowing.

Dallow was convinced. He called up an old friend at the Queensland Police Service.

Sharron, he said, was possibly not the only victim.

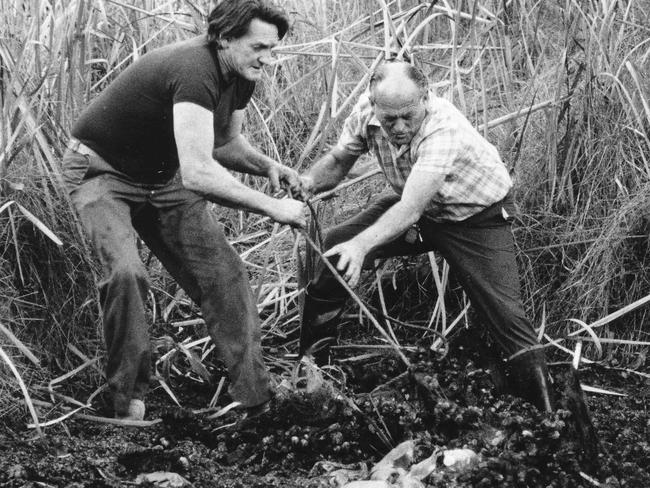

ON May 31, police gathered at the stormwater drain that runs under Cobalt St in Carole Park. It’s a busy street, lined with warehouses and industrial buildings – but in 1986, there was nothing but bushland.

Police had taken Dallow’s advice and listened to the taxi driver’s son’s story. Homicide detectives checked his claims against information in the early investigation brief. And it started checking out. They won’t say what, but the man knew things about Sharron’s disappearance that had never been made public. Things only the police and Sharron’s killer should know.

They checked into the taxi driver’s background. Spoke to his family. Built a profile. And they discovered the son was right. The taxi driver did use the dirt strip as a place to leave his car for another driver to pick up.

Police have not made public exactly what evidence they were able to gather, but it was enough to secure a crime scene warrant from a magistrate allowing them to search the drain at Carole Park. Excavators were brought in to move huge piles of earth from a muddy pit where concrete tunnels ran under the road.

It would take days, but police officers began the laborious task of filling bags with soil. Each bag would go through a sieve where they’d search for tiny bone fragments. “With recent media, we have had a person come forward that has provided the Homicide Squad with some information,” Detective Acting Superintendent Damien Hansen told media at the scene that day. “Aspects of what they say have been verified in a lot of detail from previous investigations. As a result, we’ve started excavating this scene. We’re looking for Sharron’s remains.”

In an interview with Qweekend, Det Supt Hansen says police can place the taxi driver at the Wacol snack bar. But investigating his movements has not been easy.

“You’re looking at a 30-year-old job here and the modern technology that we would rely on to track people these days – CCTV or GPS in taxis – wasn’t available 30 years ago,” he says. “And with such a high-profile job, so much has been written. People’s memories can be influenced by what they may have read or heard about it over that period of time.”

Of the hundreds of stories police have heard over the years, being able to put a suspect at the scene of the crime is a major development.

“With what we know about the facts of the investigation, (his story) is very credible,” Det Supt Hansen says. “We can say with certainty he has a reason to be in that area at that time with his work. That was a changeover point for his taxi. That puts him right at that phone box at that time.”

Police would shift 100 cubic metres of dirt from the Carole Park drain but despite a careful sifting process, there was no sign of her remains. There are no plans to conduct any further searches. It was disappointing for investigators – more so for the family. It was a glimmer of hope after a lifetime of pain. One tiny bone would have been enough to give them the answers they’d waited 30 years to get.

But despite the setback, police are still certain they’re on the right track.

Det Supt Hansen says they still have “lines of inquiry” to run out. And when they are done, they’ll look for the other victims. The taxi driver’s son had told them about the others. His dad had talked of others.

Police won’t say who. Not yet.

“Certainly the information with Sharron is specific,” Det Supt Hansen says. “The information about the other ones is nondescript.”

POLICE are keeping the identity of the taxi driverto themselves for now. There is no chance of charges being laid. The man, whose son labelled him a serial killer, has been dead since 2002. The best the Phillips family can hope for is a coronial inquiry where the information can be examined and a conclusion drawn.

But it won’t be enough for Merlesa. “He died without ever being punished. He got away with it,” she says. “I’m angry because Mum and Dad didn’t know.

“Dad only died last year. I mean, are you kidding me? You couldn’t come forward before now?

“If they think this man’s father did it, I just want to know who he is and what he did. Once that happens, I think all the accusations against my father will just disappear. I just hope this man’s family won’t be dragged through the mud. It’s not on them.

“But even if that does happen, and they do get dragged through the mud, it won’t be one per cent of what our family got for 30 years.

“And 30 years is a hell of a long time.” ■

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Rebel rocker to working for the man: Is J.C. superstar a sellout?

What would John “J.C.” Collins’ younger self think of his modern role commissioned by the state government? The local legend hazards a guess. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS

Secrets to eternal youth revealed … but it costs you $6000

Want to know the secrets to unlocking a longer and healthier life? This new clinic uses science to boost our longevity.