She can still remember what she was wearing. White shirt. Red jumper. White tights. Red skirt. It is April 1992, Jasmina Joldic is nine years old, and she is trying on her outfit to wear to school the next day. She remembers thinking “this is going to be great”. But it isn’t. Not at all. Because her father, Enver, walks in and says she and her older sister Amela will not be going to school tomorrow.

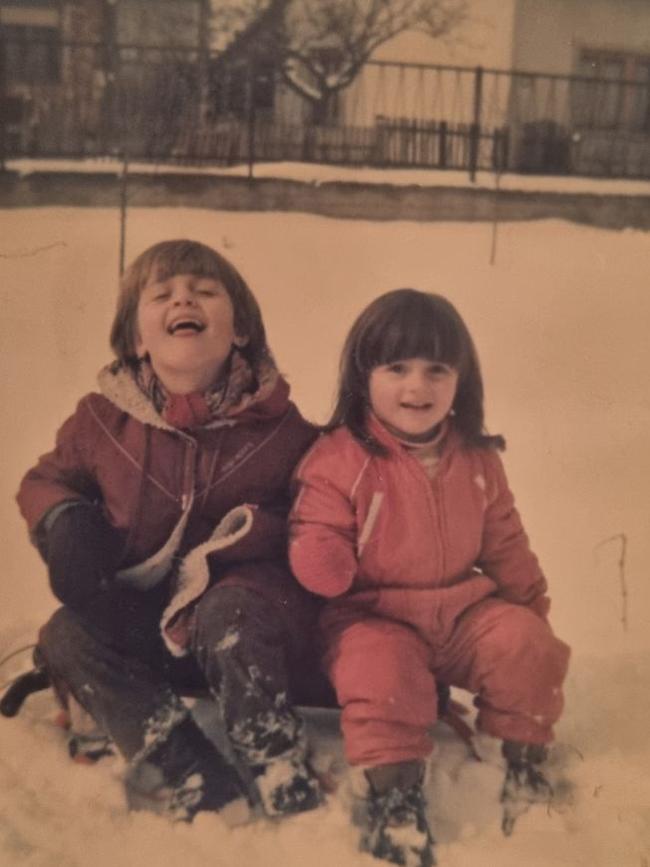

And after that, everything – her idyllic childhood in Bosnia, the family summer holidays spent bobbing up and down in the warm waters of the Adriatic Sea, the winters skiing in Sarajevo, the after-school games, the camping and hiking trips, the joy and safety of her home town, Bijeljina – vanishes. War has arrived in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and nothing is ever the same again.

Today Joldic, now 41 and director-general of Queensland’s Department of Justice and Attorney-General, looks out the window of her eagle’s nest office in the city, and remembers it all. With its soaring windows and sweeping views out to Moreton Bay, her workplace is in every way, a world (or nearly 16,000km) away from Bosnia in southern Europe. But for Joldic it is – as it is for all of us whose childhoods are etched on our skin – only as far as yesterday.

“There were suddenly barricades on the streets and my sister and I were just not understanding at all,” she says. “Mum and Dad were saying ‘It’s just a bit of unrest; don’t worry, it will be fine, it will be fine’.

“They tried so hard to keep our lives going normally for us, and then we came downstairs one day and our mother was cleaning the kitchen, but she was cleaning the exact spot over and over again. And we knew something was wrong. We asked what was happening and then we asked where our father was. And she said that he had been taken away for questioning, but they would bring him back soon. Which wasn’t true.”

Instead, Enver Joldic, now 68, along with his brother – and like thousands of other Bosnian men – had been taken by the Serbian army to a concentration camp.

“They took him – this man who would not step on an ant, the kindest and gentlest of men – with only the singlet and shorts he was wearing, nothing else, and we did not know where he was, and we did not know for months,” Jasmina Joldic says.

Her mother Selma, now 65, an economist, kept “putting her high heels on, getting dressed and going to work, and telling us we were going to find our father, because that’s the right thing to do when you are a parent. And that’s how adults normalise war to their children, to try to keep them unafraid”.

Selma Joldic was also determined her daughters would continue their education, and they did – until a bomb was planted in one of the classroom desks, and the teacher told the parents she could no longer guarantee the children’s safety. The teacher’s name was Nermina Pasalic. Joldic remembers her name, just as she remembers the names of all who helped her and her family along the way. Joldic asks if some could be acknowledged in this article, because it is also the right thing to do.

The sisters went home, and in November that year, a stranger appeared in their driveway. Shockingly thin, covered in dirt and mud, Enver Joldic was home.

“I did not recognise my father at first; he was so skinny, so filthy and so weak,” she says. “My father and my uncle were the only two survivors of that camp from our town.

“We are not sure why they were released, but they were released on the condition that they would join the Serbian army. And there was no way my father was going to shoot anyone. So … ”

That night the entire family fled, carrying one small bag each. They didn’t tell anyone. They didn’t say goodbye to anyone. The Joldic family was on the run. Her childhood, Jasmina Joldic says, was officially over.

As director-general of the Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Joldic is in charge of a portfolio with more than 4000 staff. Appointed in December 2023 at 41, she is considered young for the position. She is also one of only four women who are directors-general. Joldic is the first and only one from a non-English speaking background, but is determined she won’t be the last.

Sometimes mistaken for a junior staffer, Joldic has been asked more than once in her career to fetch the coffee. Once, coming back to the office from her daily evening jog, she realised she had left her pass behind. Trying to get back in, Joldic was stopped by a security guard who told her she could not enter the director-general’s office.

“But I am the director-general,” she told him. No dice. She asked him politely – because Joldic is unfailingly polite – if he would accompany her to her office so she could show him her pass. He said yes. She produced the pass. He was embarrassed and apologetic. No need, she told him – an easy mistake.

This is Joldic’s style: unruffled, professional, courteous. And no one who has worked with her is surprised by her rapid ascent through the public service ranks.

Joldic graduated with a Bachelor of Arts with honours from the University of Queensland in 2005 and worked in social and international policy in the federal Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in Canberra. She then worked for three years for the vice-chancellor of University of Melbourne, Professor Glyn Davis, before returning to Brisbane in 2012 to work in the Queensland public service, followed by the University of Queensland.

Various senior policy adviser roles followed, and she joined the Department of Health from 2016 to 2021, working closely with chief health officer Dr Jeannette Young. She was appointed associate director-general of that department in 2022.

Along the way, she was awarded a Public Service Medal in 2022 for her work during the Covid-19 pandemic, and last year, after completing her Graduate Certificate in Policy Analysis and Master of Public Administration, she received the Griffith University and Griffith Business School Alumnus of the Year Award.

All of which is to say Joldic is a sky-high over achiever, an exceptionally hard worker and a firm believer in the value of lifelong education and public service. She has seen first hand how it only takes one person to change another’s life, and has spent her life trying to do the same.

And all of these achievements, awards, and beliefs stem from what happened to her family after the night they fled their home, holding nothing in their arms but their small bags and each other.

“I was very scared,” Joldic says of the bus journey from Bosnia into Serbia with her sister, a cousin and her aunt shortly after they had left their home in the dead of night.

“I remember exactly where I was sitting on that bus. My aunt told us to say nothing when we were stopped at the checkpoint, and she managed to convince them that we were all her children, and she didn’t have the paperwork because we were just popping across for the morning to visit family.

“I stayed silent. You play the role you are told to. I was no longer a child; I understood that. So you don’t cry and you don’t show you are scared; you just follow the instructions. My aunt checked us into a dodgy hotel. My parents weren’t with us – it was too dangerous for us all to go together – so they had to cross a river by boat, a tinny, and they could have been shot in that crossing. We waited all night for them in that hotel room, and when my aunty thought we were asleep she spoke to her mother and said ‘If they don’t come, I will have to take the children myself’, and my sister whispered to me ‘they will come; they will not leave us alone’.”

Two days later, in the early hours of the morning, there was a knock at the door. Enver and Selma Joldic had crossed the river safely. Another aunt on her father’s side was a professor at a Berlin university. She would give them shelter, she said, if they could cross the border into Germany. The family managed to travel by train to a small town on the Czechoslovakian (now the Czech Republic) side, and from there they tried again and again to reach Rosenthal-Bielatal in Germany. After attempts by train and car failed – and with the locals becoming suspicious – Enver Joldic decided they would try something ambitious. Obvious. A little bit crazy. They would walk across the border.

“We left in the dead of night,” Jasmina Joldic says. “It was freezing. It was raining. It was snowing. We hid in a train station bathroom, and then my father took my hand and we walked across that border like we were out for an evening stroll. Dad said, ‘Don’t say anything, don’t speed up, just walk normally’, and I don’t know why, but they just let us cross’.”

It is November 1992, and the Joldics have finally made it to safety … almost.

“My aunt came to pick us up in a cab, and I remember her talking to the cab driver, and even though I couldn’t understand German I knew something was wrong,” Joldic says. The driver wanted to take the family straight to the police station.

“But she just kept talking and talking and then he started to cry as she told him our story, and he drove through the night and took us to Berlin.”

A new city, crowded refugee accommodation and a new school followed, her parents insisting their two daughters attend a German school, learn the language, and complete their education.

“I couldn’t understand a word anyone said. Not a word. It was hard, because you are a refugee; you are a second-class citizen. You’re frowned upon, and it is made very clear to you that you are not welcome.”

But for every person who made her family feel unsafe or insecure, who told them to go back where they came from, there were, she says, “many German people” who helped the Joldics, including her German language teacher, Michael Carl.

“Herr Carl spent a lot of time with me helping me learn German,” she says. “My whole life has been marked by people who believed in me more than what I believed in myself. I will never forget all the kindness that has been shown to me, and I try to do the same.”

Joldic learnt German in six months (“It’s easier when you are young”) and by the time she finished school at 17, she was top of her class. Her parents refused to accept social security benefits and eschewed their former professions – Enver Joldic had been a mechanical engineer – to work as a manual labourer and a cleaner.

They would spend sevenyears in Germany, obliged to reapply for their visas every six months. When told the next time they applied, only Enver would be allowed to stay, the family applied to live in Australia in late 1999. In early 2000, they received word that they could, and for a reason none of them expected.

“When Dad was taken to the concentration camp, one day the Red Cross were allowed in for the first and only time, and just for a very short time,” Jasmina Joldic says. “In that time, they had registered my father’s name.”

And, because Enver Joldic’s name was on official documentation as a prisoner, the family were astounded to learn that they were eligible to relocate to Australia, the US or Canada. They chose Australia, specifically Brisbane, “because they told us how sunny it was”, she laughs.

“The immigration official said to us ‘it’s people like you that the country needs’, and it was the best thing to hear because, finally, finally someone wants us.”

The family arrived in Brisbane in April 2000 and moved into temporary migration units in Stones Corner. Eventually they would move out, the sisters would attend Coorparoo State High, both would do very well and both would go to university. They would make lifelong friends, their parents would find work in their professions, and this should be the happy ending for Jasmina Joldic – the one where all her dreams come true.

And for a time, they did. She rose through the ranks of the public service to become one of Queensland’s most senior executives, met and married her husband, Emir Jandric, and they had the most beautiful baby. But she would need every ounce of courage and all the love that people had shown her to face the next chapter of her story.

There is a picture of BenjaminJandric on the bureau in Jasmina Joldic’s eagle’s nest office.

Born on March 5, 2013, Benjamin, known as Ben, is a tousle-haired, rosy-cheeked, bright-eyed delight, adored by his parents, loved by their families – and representative of a new generation, a new way of life growing up in a safe place.

And then, on August 27, 2015, Ben tells his mother he has a headache. He is 2½ years old. His mother takes him to the doctor, who thinks he has the flu, so she takes him home.

But he doesn’t get better, so she takes him again.

Both parents feel something is wrong, so they take him to the Children’s Hospital’s emergency department, and Joldic stays overnight with Ben while tests are run. They stay with him through the scan that shows a brain tumour the size of a tennis ball, and they stay with him during his first surgery and all through the months and years of treatment that every parent of a seriously ill child knows.

They stay with him through seven surgeries, radiation treatments, proton therapy in Japan, hyperthermia treatment in Germany, all the medications, the seizures and the long hospital stays, and they stay with him right until their beautiful boy takes his last breath on January 6, 2019. Ben was five years and 10 months old. And he was, his mother says, funny and brave and energetic and kind.

“Kids hate taking tablets; he would take them with no fuss. All the treatments, no fuss,” she says. “We never let him know something was seriously wrong with him, and in the meantime we spent our days and nights looking after him, researching everything we could. I would get up in the middle of the night and talk to a doctor in Hawaii, to have a Zoom meeting with someone in Russia, in Germany. You name it, we left no stone unturned. And we never, ever thought for one second that we would lose him.”

But they did, and at the very end of his short and beloved life, she held him, her boy in her arms, close to her chest, close to her love, where she holds him still.

Joldic would like peopleto know about her son Ben, and how loved he was – and is – by all her family and the many clinicians who treated him. She would like people to know how grateful she is to her parents, family and friends who supported her and Jandric through Ben’s illness and ever since.

Joldic is also grateful to her colleagues, past and present, who have championed her throughout her career, and continue to do so today. People like Dr Young, Professor Davis, former senior public servants Rachel Hunter and Michael Walsh.

But there is something else she would like people to know, and it is the main reason this deeply private woman is telling her story.

“For a long time, I have not told it,” she says. “I’ve told bits and pieces to people who are close to me, but I think I am a good example of not giving up. I’ve had messages of support from young girls and boys, including those from non-English speaking backgrounds, who say they have never seen anyone who looks like me and sounds like me in such a role. And in this role, I can make a difference. Public service can make a difference to people’s lives. I’ve seen it, and I’ve lived it.

“People ask me how I kept going after Ben died. I went back to work two weeks later, and some people couldn’t understand that. But I did what my mother did all those years ago: put my heels back on, got dressed and walked out the door.

“Because I know I can help other people in this role. It is a privilege and a great responsibility to help others but also to give back to a country that has given my family and me a new life, a renewed sense of belonging.”

And because, she says, cradling the photo of Ben in her hands, “my son taught me that life is worth fighting for”.

How this unlikely ‘surrogate father’ found himself in the Hornet’s corner

Despite having no prior background in boxing or sports management, entrepreneur Phil Murphy funded Jeff Horn and another boxer. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS

Rebel rocker to working for the man: Is J.C. superstar a sellout?

What would John “J.C.” Collins’ younger self think of his modern role commissioned by the state government? The local legend hazards a guess. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS