IN DECEMBER 1956 my mother and father packed our entire possessions into the back of a ute owned by their good friend Bobby Burns and we drove a mile or so south from Maroubra Junction to a sandhill at South Matraville where, on land recently bulldozed, houses of brick, weatherboard and fibro were being hammered and heaved into existence.

A new suburb being spread on the sandhills.

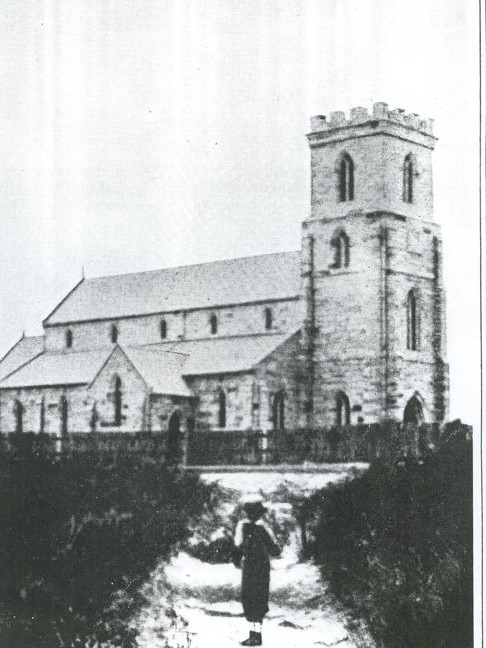

My parents, Ted and Phyllis, had met in the army, married at St Jude’s Anglican Church at Randwick in 1946 and settled down with my mother’s mother in a 1920s cottage two blocks off Maroubra Junction and the tramline that ran along Anzac Parade.

Maroubra Junction, or just ‘the Junction’, had a big bakery from which horse-drawn carts trotted out every morning making deliveries of fragrant loaves.

Our back lane was often heaped with horse manure.

The Junction was distinguished by two cinemas, the Amusu and the Vocalist, set among strips of shops, two pubs and an RSL Club.

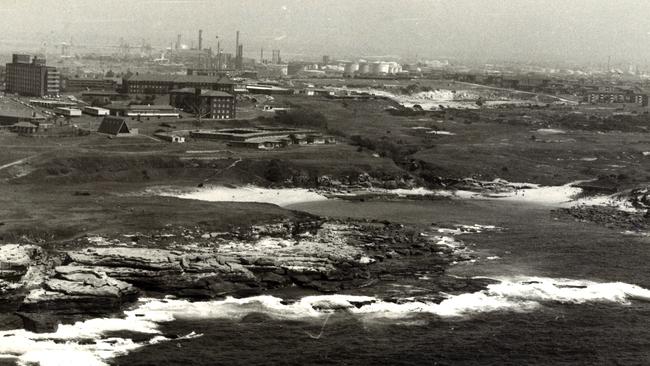

My maternal grandmother died in 1956 and her house had to be sold, so my father secured a War Service loan for a block of land and a fibro cottage on that sandhill at South Matraville. Further south stood the state’s biggest gaol, Long Bay; one of its biggest hospitals, Prince Henry; and the suburb of La Perouse with the Aboriginal settlement, a memorial to the French explorer, a snake pit, boomerang stall, fish and chip shop on a jetty and four little beaches sometimes polluted with oil from tankers.

Around our new home at South Matraville, brand-new houses were accommodating war veterans like my father in a grid of streets, laid out over bulldozed scrubalnds.

I never thought of it then but our subdivision was the first layer of European civilisation spread on this ancient coastal landscape. Before us, the scrub had stood, regularly fired and occupied by Aboriginal peoples but otherwise undisturbed for hundreds of thousands of years. Longer? Who knows?

RELATED:

Carr: Diaries for a first-class tosser

It was close to the beginning of Australia’s modern story, the place of the first landings of Europeans, James Cook in 1770, and Arthur Phillip and Jean-François de Galaup La Pérouse in 1788.

These Europeans would have explored these sandhills, scratched their stockings on these shrubs, peered across swamps at native camps, been startled when wallabies thumped off into the bush.

CARR: I COULD HAVE BEEN KINDER AS NSW PREMIER

The sandstone cliffs looked — just as Robert Hughes was to put it in his book The Fatal Shore — as if they could snap off like a biscuit.

This was a world of coastal dunes, heathland and woodlands of angophoras, lilly pillies and tree ferns sheltering in the gullies.

Eastern suburbs banksia were everywhere, 2 to 3 metres in height — able to grow on the white-grey soil of the dunes, and then fading out where coastal heath sprang from thin soils on sandstone.

In the damper areas there were scribbly gums, red gums and bangalay eucalypt.

As a kid I saw all this as nondescript bushland, great for games of secret armies, ‘virgin’ land waiting to be uprooted for housing.

Now it is seen as part of Sydney metro’s ‘biodiversity hot spot’.

The bush we poked around in as 12-year-olds, a little guerrilla army spending a day out on the western fringe of the rifle range, with lunch in our haversacks, hiding, scouting, scrambling. This bush? A hot spot? ‘Yes,’ explains Matt, the local council’s biodiversity officer.

‘The banksia scrub alone was very rich in species — about nine species of it in the Sydney basin. It fades into sedge land, she-oak swamp around what became the south Maroubra speedway …’

In my memory is a shaky recollection of a speedway just beyond the corner of Anzac Parade and Fitzgerald Avenue, and banksia scrub, and even — this is deeply embedded — some blacks, or perhaps just a single Aboriginal person, squatting there, in that scrub in a humpy on the fringe of the bushland.

Say, in 1955 or ’56.

Certainly years later I recall an Aboriginal woman lived in a humpy on the edge of the rifle range just off Cromwell Park opposite Malabar Public School.

I worked in a holiday job with a Randwick Council crew tending parks and gardens, and a couple of the labourers talked about her; they said she offered sexual favours, in what might be seen as an age-old ritual, an Aboriginal woman on the edge of white settlements.

We moved into that cottage at South Matraville in December 1956, a grey painted fibro cottage with a turquoise painted front door, on land where every last banksia had been bulldozed and rooted out to produce sandhills

Anyway, this was a great place for kids to run wild. Even as a kid I had a sense — literally a smell in my nostrils, of seaweed and sedge land — of what this La Perouse peninsula must have been like when the Aboriginal peoples roamed on it: scrubby land running down to the beach sand and dragging surf, rocky headlands, a wonderland of swamps on the Botany side, everywhere the banksia.

If I were transported back in a time machine nothing about it would surprise; I had tasted enough of it before it was all built out to have captured its flavour and locked it in my memory.

In Kangaroo, his book set in 1920s Australia, DH Lawrence referred to buildings flung across the landscape, in his case, the northern beaches where, in one chapter, his characters had gone on an excursion. Flung over the landscape.

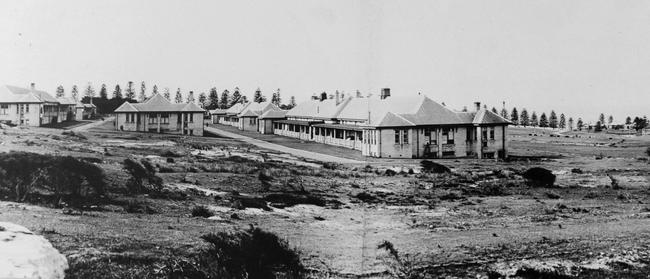

I had the same feeling about this peninsula we lived on when we trespassed on the grounds of Prince Henry Hospital, once called the Infectious Diseases Hospital, or, with torches and candles, entered the tunnels that linked World War II gun emplacements on the Malabar Headland, or sat down in an old tea house in La Perouse looking like it went back to days before World War I.

We were seeing the first layer, the first flimsy attempts at constructing a European settlement, the first buildings thrown up on a pristine land that had been millions of years in the making.

We moved into that cottage at South Matraville in December 1956, a grey painted fibro cottage with a turquoise painted front door, on land where every last banksia had been bulldozed and rooted out to produce sandhills — not a blade of grass remaining — served by a tramline that ran from Circular Quay to La Perouse, originally to take visitors to Long Bay Gaol and to Prince Henry Hospital.

Around the corner from our new house stood something that was entirely out of place, as if deposited by extraterrestrials: a mysterious building approached by a ramp and protected by a high wall of yellow brick.

It was barricaded and looped with barbed wire that stopped us climbing over; it seemed to serve some storage purpose but remained a mystery all the years we lived there. The ramp became a good starting-off point for our billycart races.

Only in researching this did I find that the structure had been opened in 1932, planted in the scrub, as a state-of-the-art incinerator.

Its architect had been Walter Burley Griffin. He had crafted art deco touches that had been lost by the time we moved out to Matraville, just as medieval cathedrals had their relief sculptures chipped off by revolutionaries.

Incinerators were the emblem of 1930s progressivism, this one an alternative to open garbage dumps. It was closed in 1943 and garbage was no longer burnt but dumped at Malabar down the road.

The distinguished building in 1954 became storage for light industrial purposes, a mysterious presence when we moved into the area.

Next to it stood the depot and disposal point for the sewage trucks that visited our homes twice a week to lug off the brimming pans of human waste, and a huge chimney.

It was the vent for the main sewage tunnel that passed right under our neighbourhood to spill its contents at the Malabar Headland; chugging out, barely treated, at cliff face and sea level.

In fact the whole peninsula was gloriously, unapologetically polluted and flavoured by sewage disposal, the open garbage dump at Malabar with rats scrambling over Randwick Municipality’s household waste, waste from the hospital and rich fresh sewage.

Meanwhile, up the road the only leprosarium in the state (in the nation?) accommodated quarantine patients behind sandstone walls in the grounds of the hospital.

There were the grey-brown structures of Long Bay Gaol, cruel and, yes, Dickensian. Occasionally a prisoner might vault the walls or get smuggled out in a laundry basket, a desperado lurking in the banksia who might slash his way into our house through the flyscreens on the windows, although the back door was never locked in all the nights I lived there as a kid.

When Mum took us to sit on Yarra Bay beach we could smell and taste the oil pollution in the waters of Botany Bay, the water having been warmed as it passed through the bowels of the adjacent Bunnerong Power Station, whose chimneys were sending plumes of pollution to flavour the air we breathed.

The old Australia was all around. At Bare Island, La Perouse, an old fort provided primitive accommodation for veterans of World War I.

If we entered on weekends they could be seen, sitting in the sun, blankets over their knees. Once I and my English migrant friends cycled out to Malabar Headland to explore an old concrete gun emplacement installed in World War II. In it lived a harmless, homeless old fella in a greatcoat who laid out sliced bread to toast in the sun.

‘This is my home,’ he told us, as if we 14-year-olds had arrived to displace him. He wanted to be called Digger and said he had known this area since he had done rifle training in the adjacent range in the lead-up to World War I.

Drawn to the homeless life, sleeping rough, he had chosen to live in the old gun emplacement that had been constructed to protect us from a Japanese coastal invasion in the more recent war.

From Maroubra to La Perouse, along Anzac Parade and its tramline, there was no pub. The RSL clubs at Maroubra and Malabar stood as bastions of social life

At my first day at the start of the 1957 school year I arrived at Matraville Soldiers’ Settlement Public School with my sister Lynda, walking the half-dozen blocks from our new fibro home. There was a huge building like a hangar directly opposite the school with its six weatherboard classrooms.

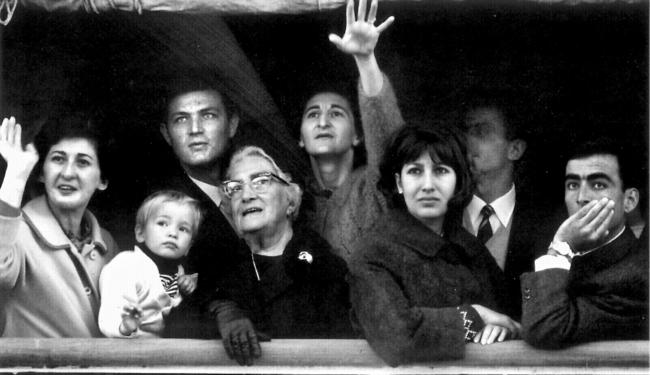

It had been used as army storage but now walls had been thrown up inside to create makeshift rooms. It was a hostel for migrant families who shared the common ceiling. There were no windows, no air conditioning and, of course, they had collective bathrooms, dining room and kitchen.

As I stood nervously at my Year Four desk in that detached timber classroom, six German girls walked in with their plaits and their embroidered blouses and their skirts, looking like they had been marshalled to perform a folk song and dance.

In fact, they were part of this community of Dutch and Germans who, within a year or two, would leave the hostel and melt into the Australian population, their memories of Hamburg or Wuppertal or Rotterdam fading in the unforgiving Australian sun.

A few blocks away on Bunnerong Road, Pagewood, stood another vast hangar-like army storage complex turned into a hostel for British migrants. The conditions were just as crude.

It was a five- minute walk to the General Motors plant at Pagewood and not far from the Leyland plant at Moore Park, plus a vast glassworks.

These traditional manufacturing industries were there to soak up the fathers of the English youngsters who would attend Matraville High with me.

So this is where history had deposited us, this family of Ted Carr’s, train driver and soldier, himself from a family of eight, his father a train driver too. Here we were, just south of Sydney. Here were old Aboriginal people lingering in a settlement at La Perouse, one or two of them living in the bushes.

Here was bushland bulldozed for the houses of World War II veterans and their young families, servicemen set up in private home ownership.

With the war behind us, Australia had embarked on force-fed population growth, filling the empty spaces with British, Germans, Dutch. Around us a raft of traditional polluting manufacturing industries ran in an industrial belt down the edge of a residential zoning.

This was the world in which I grew up. It was fantastic.

When at the start of fourth year at Matraville High School I started to learn about the economy, with an old Marxist, Soviet-line teacher called Sam Lewis who was a big shot in the Teachers Federation, I became enchanted with the idea of this industrial Australia, an Australia with factories.

I remember one Saturday morning heading off on my bike and cycling through the industrial streets of Botany’s industrial zone, all quietened for the weekend. My country! I marvelled that Australia had serious secondary industry, churning out cars, chemicals, bottles.

We were industrialising just as the United States had done in the nineteenth century.

I thought it was thrilling that we were boosting our population.

The conventional wisdom was that northern European migrants were more productive and better citizens than any others; although the Mediterranean migrants, someone had warned my dad, those Greeks and Italians, would soon reach our area, as they had other suburbs.

He had come home one day from Malabar RSL Club, repeating the prediction.

This couldn’t be stopped. When one of my English migrant friends returned disappointed with his family to Manchester I thought this a blow to the idea of North European Australia.

Kevin and his family — working-class English — were precisely the nation-building migrants we needed, I thought, as a 14-year-old.

And my father was a strong supporter of White Australia on the grounds we should stay homogenous and not introduce the implacable race problems that were causing such tension in other countries. I thought this unarguable wisdom.

Out on this peninsula there was not a single restaurant, at Maroubra Junction only a hamburger joint.

The arrival of a single Chinese restaurant would be sometime in the ’60s. From Maroubra to La Perouse, along Anzac Parade and its tramline, there was no pub.

The RSL clubs at Maroubra and Malabar stood as bastions of social life.

The arrival of takeaway Chinese at Malabar RSL, sometime in the mid to late ’60s, would be the harbinger of a services economy, although in our economics class there was some reference to the danger of us ending up ‘a milk bar economy’ — too much in services, too little in making things.

There were no single-parent families, in the neighbourhood that I knew. No divorces. There was no talk of alcohol at school. Friends of my parents would visit and drink beer or Porphyry Pearl and eat tomato sandwiches, and talk of crime stories and other tabloid gossip

Clearly a danger to be avoided.

‘Australia Unlimited’ — The Sydney Morning Herald featured this as an annual supplement — would be created by assembly lines, dams, power stations, steel plants built by immigrant labour recruited from bombed-out cities, displaced-persons camps and the olive groves of southern Europe.

The prevailing ideologies? Sorry, too grand a word. Let’s call it the prevailing ethos, ways of thinking: what were they?

Overshadowed as we were by World War II, the status and standing of the ex-serviceman and his family was one of the foundations of life, here on the edge of the city. We were a nation that went to war: a warrior race.

Our high school principal, Robert Mobbs, with his wavy hair and petite moustache and military bearing with pulled-back shoulders, had been born in 1910 and had served as a lieutenant in New Guinea.

Before the war he had been Sydney University’s youngest student, devouring subjects I would have loved: Latin, German, French. Now he was at this job, setting up a brand-new high school with me and my friends as the foundation students.

‘Your fathers fought in the war,’ he declared at assembly. ‘And now they’re showing the same spirit by building and owning their own houses.’

The ex-serviceman and his family deserved a house of their own.

My father once ran into my principal at Malabar RSL and was to quote his wisdom.

One day, it was to be assumed, my friends and I might get called up. Would we be up to the soldiering of our fathers?

We were, too, part of industrial Australia. A notion of us as a manufacturing nation dominated the psychic landscape as opposed to Australia as a primary producer or a nation of bankers or accountants. There was an ethos, too, of labourism.

The men who worked in those industries and the wives they supported were working class; more or less, self-consciously so. And they showed it by belonging to trade unions — over 50 per cent of the workforce was unionised — and by voting for Labor candidates in local, state and federal elections.

There were no single-parent families, in the neighbourhood that I knew. No divorces. There was no talk of alcohol at school.

Friends of my parents would visit and drink beer or Porphyry Pearl and eat tomato sandwiches, and talk of crime stories and other tabloid gossip.

Every Sunday we were dressed up and sent on the tram, from our fibro house on the sandhills at South Matraville back to Maroubra Junction — to Robey Street where we used to live — to the Sunday school at St Andrew’s Presbyterian church.

My parents had sent me there only because it was close, just across the road from our first home. Both of them had traces of Catholicism in their background but believed something of a religious education was necessary.

So I learnt the Sunday school hymns: Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so. Goodbye, goodbye, we will be kind and true.

From one lesson I picked up a fear of alcohol. I remember a warning about wine. It comes along ‘as a merry little fellow’ and tempts us and traps us.

Suspicious of the stuff, I didn’t drink until I was twenty-three. I was certain that God existed and the stories were true, even joining the Inter-School Christian Fellowship.

But at fifteen or sixteen my faith evaporated in the Sydney Domain one Sunday afternoon as I listened to a mocking Rationalist Society orator standing on a fold-up platform under a fig tree.

‘There have been thirty-three virgin births,’ mocked Charlie, the scurrilous, all-purpose speaker for the Rationalists.

‘If your daughter came home with a baby and said she had found it in the bulrushes, what would you do?’

The religion I discovered around this time was that of politics, though it was not fed by Domain orators; I had an inherent suspicion of the communists.

How wrong, I thought, to end up apologising for everything the Soviet Union did, although, glancing at its propaganda magazines with titles like Soviet Reconstructs, I could see that the Russian Revolution had worked; they led the West in science, technology, education and culture, and the horizon-to-horizon collective farming was plainly more efficient than our ramshackle agriculture with our sad little farms.

Anyway, capitalism and communism were converging at the centre; Dad had said something to that effect.

A strong mythology was provided by my father’s running commentary on the news of the day, mocking Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies and talking up Labor. And my uncle Bern talked about Professor Fin Crisp’s biography of Ben Chifley, which he had got from his local library.

Published in 1961 it was kind of a Labor bible. Overnight I dropped my childhood ambition of being a newspaper cartoonist — I had gone to Saturday morning art classes at East Sydney Tech and had bought a series of books on how to be an illustrator — and decided I wanted to be a career politician, and as a result joined the Malabar — South Matraville branch of the Australian Labor Party.

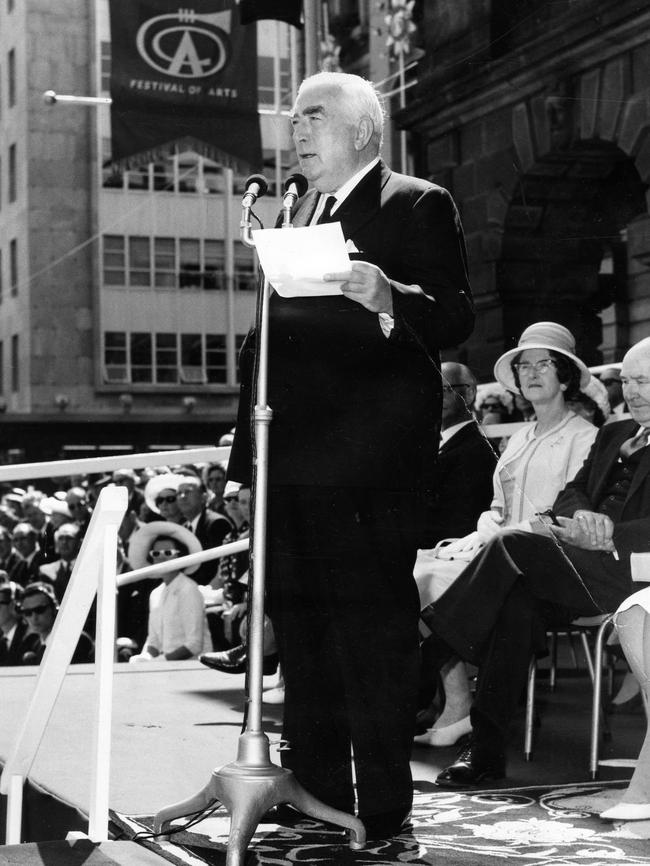

Our local state member was Bob Heffron, former seaman and radical unionist then premier, who had been elected member for Botany in 1930 and served as minister for education in the long-term Labor government that took power in New South Wales in 1941.

He now wore striped trousers and a Homburg and was mocked in Jack Lang’s Century as Mister Magoo.

The local federal member was Danny Curtin, a former boilermaker who fluked Labor preselection for the seat of Kingsford-Smith in 1955.

During the Depression he was said to have sold prawns on railway stations. He would never be more than a time-serving backbencher, sometimes making a raucous interjection when Prime Minister Menzies was speaking.

When I was to appear in the local ALP branch he called me ‘Young Robby’ (which later amused Paul Keating) and teased me: ‘You’re not after my seat?’

I recall that soon after we had moved into our fibro cottage at Matraville, one weekend he had come knocking on the door to introduce himself to new residents like my parents, and my dad had invited him in for a cup of tea.

When he left my father had said, ‘Did you notice he had a missing finger on a hand … an industrial accident. He was a boilermaker.’

I wasn’t content to just sit at meetings of the branch on the second Monday of every month in an infants’ classroom at Malabar Public School. I was impatient to signal that I was in the party to get into parliament.

I wanted indeed, one day, to hold the federal seat. I had to impress these adult branch members.

Three months after joining, I — a kid of fifteen — resolved that I would move two motions at the branch meeting. One would commit the party to preserving Ben Chifley’s house in Bathurst as an historic memorial.

I had read the collection of Chifley’s speeches and the biography recommended by my uncle. The second motion would urge the Labor Party to set up its own newspaper. Perhaps these motions signalled an early interest in history and publicity.

I was terribly nervous, walking down to that branch meeting. As I recalled in my book Thoughtlines, the boy stands on the stairs of Malabar Public School. There are moths under the outside light and the sound of scraping chairs and loud voices in a classroom as the members get the meeting ready.

The boy’s heart beats hard. He is mad to do this, he will only make a fool of himself — going in there, and with a few months’ membership behind him, telling the party what to do.

Better to forget his carefully worded motions and just sit silently.

But listen, another voice demands, you have no choice. You are fated to do this. This will be your life and you know it. And you have no time to waste. A man his father’s age officially declares open the monthly meeting of the Malabar — South Matraville branch of the Australian Labor Party.

The boy mounts the stairs.

Oh, what a gift to have been born into the working class! Oh, what a gift to have had those parents — and our little fibro house on the sand! And not to have had any advantages! No books there, no TV, no subscriptions except The Sydney Morning Herald, my window on the world, and Reader’s Digest. Just magazines and papers Dad might have picked up on the passenger seats of the train. Always ABC radio — for news, parliament, cricket and tennis. For big public events the radio would be moved from the kitchen to sit on the ironing board, and we would sit at the kitchen table and listen to the broadcast of Princess Margaret’s wedding or the policy speeches in a federal or state election.

No private school scholarship, no interstate trips, no airline travel; no powerful family friends or contacts. No expectations. Just every fortnight the council’s mobile library van and the books at school, and every month the Labor branch meeting in the infants’ classroom at Malabar Public School. Just an invitation to live off one’s wits. And a growing hunger, and a yawning curiosity to see what the great adventure might offer, like a career open to talent.

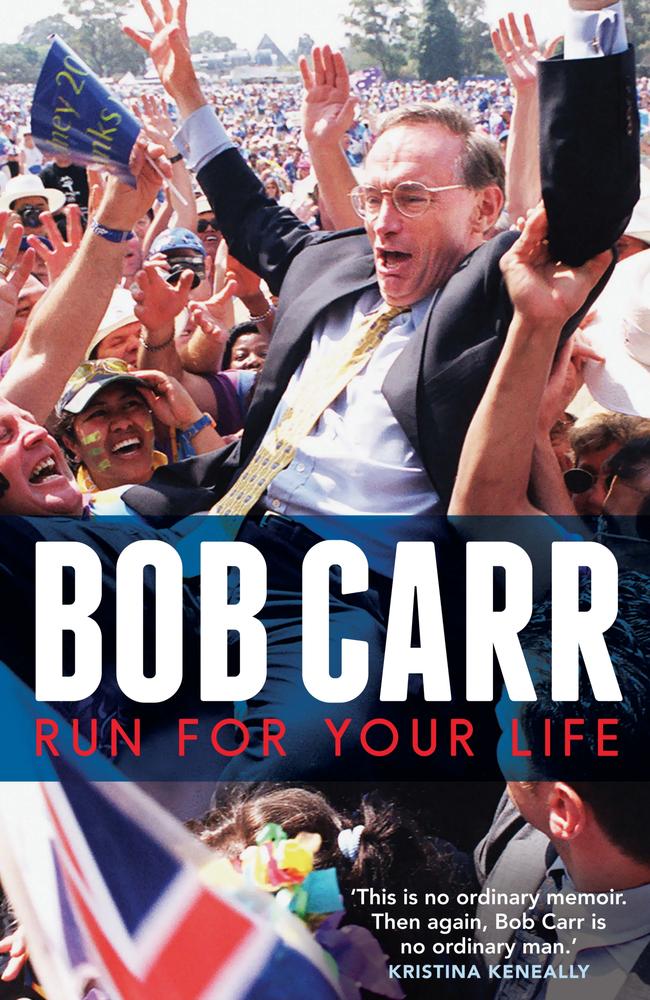

This is an extract from Run For Your Life by former NSW Premier Bob Carr (Melbourne University Press, $34.99, available June 27). All author proceeds are being donated to charity Australia for UNHCR help children displaced by the Syrian Civil War.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As autumn moves towards winter what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As autumn moves towards winter what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.