HE’S Australia’s most successful athlete you’ve probably never heard of.

Strolling among the vendors hawking two foot-long chilli dogs and the salted peanut stands at the Sydney Cricket Ground earlier this year, when America’s Major League Baseball came to town, was a tall, amiable bloke called David Nilsson.

For two days only, the SCG was transformed into a bona fide red, white and blue ball park, attracting some 80,000 fans, and an event where Nilsson, 44, felt right at home.

The small-business owner from Bridgeman Downs in Brisbane’s northwest could be seen shooting the breeze with MLB’s most powerful man, Commissioner Bud Selig, chatting with the crew from ESPN, America’s leading cable sports channel, and trading high fives with star players from the LA Dodgers and Arizona Diamondbacks.

Because while many in his home state of Queensland may not know Nilsson, they sure do know him in American baseball circles – particularly in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, home of the beloved Milwaukee Brewers where Nilsson was once the team’s favourite, if imported, son.

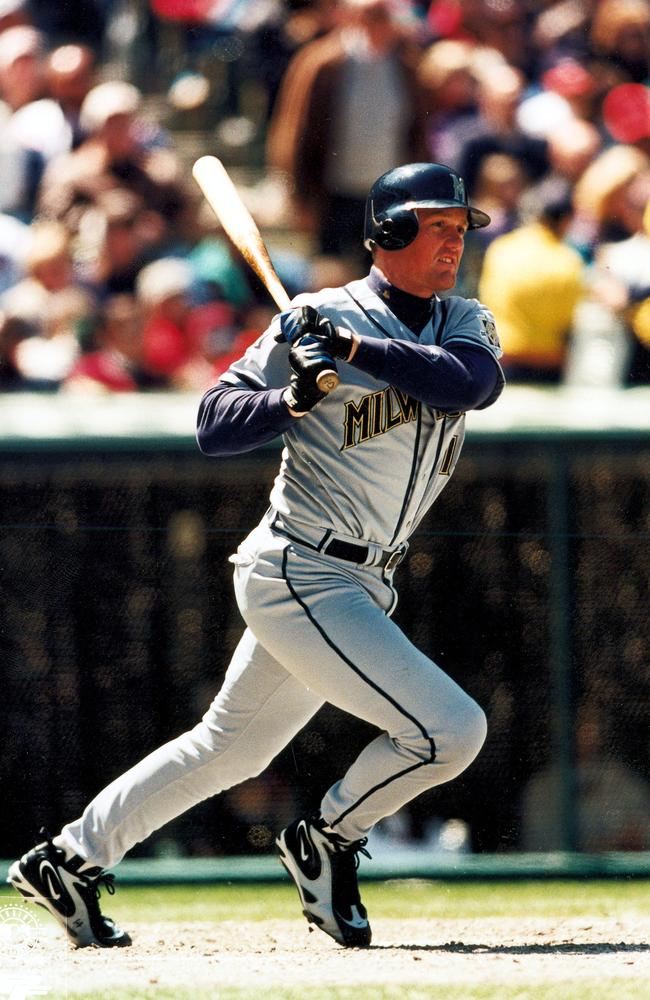

For eight years, from 1992 to 1999, Nilsson was the Brewers’ star catcher, a 193cm southpaw who’d earned the fans’ respect and gained two nicknames – “Dingo” and the “Thunder from Down Under” – along the way.

Rated in the MLB’s 2013 Power Rankings as the “greatest catcher in Milwaukee Brewers history”,

Nilsson was inducted into the team’s Hall of Fame in May this year. And in the intensely competitive world of American baseball, Nilsson won coveted selection in the 1999 All-Stars team.

Each year’s All-Stars, selected from the MLB’s 30 teams, are voted for by coaches and fans. Until last year - when Grant Balfour, originally of NSW and now playing for the Tampa Bay Rays, was selected - no other Australian had made the cut.

Over 1000 games and 105 home runs, “Dingo” Nilsson was one of baseball’s big hitters, both literally and lucratively. In 1999, he was Australia’s second-highest earning sportsman behind golfer Greg Norman, and during the ’90s he made a fortune, his final three-year deal with the Brewers rumoured to have been worth $US20 million.

When Nilsson left the Brewers, he signed with Japan’s Chunichi Dragons for a one-year multimillion-dollar contract; later, he flirted with joining the Boston Red Sox or perhaps the New York Yankees, both of which had approached him at different times, but instead took the Australian baseball team to two Olympic Games.

And then, he walked away.

His frame fills the doorway, his torso momentarily blocking out the sun behind it, his handshake surprisingly gentle. “Hello,” David Nilsson says quietly, “thank you for inviting me.”

For a man with his own set of baseball cards, Nilsson – married to Amanda and father to Jacob, 16, Tyla, 14, Grace, 7, Ashleigh, 5, and Elijah, 3 – is polite, self-effacing and modest, to a point.

Later, when asked if his freakish talent for baseball was evident at an early age, he answers somewhat haltingly: “I don’t ever recall, in my own age group, um, being average.”

His profile may be lower than those of his contemporaries inducted into the Sports Australia Hall of Fame in 2008 – Ian Thorpe, Alisa Camplin and Todd Woodbridge – but then the game in which he excelled is still finding its feet in this country.

While its popularity is growing – with Australian Baseball League attendance figures steadily increasing from 114,000 in its first 2010-2011 season to 148,000 in 2013-14 – it’s unlikely to ever attain the stature it has in the United States, where last year 74 million spectators attended MLB games.

Competition for a place in an MLB team starts with a dog-paddle through thousands of little league games in the hope of being spotted, then a long, slow slog through the minor leagues, starting at the very bottom of the tank, and hoping to come up for air long enough to be plucked from obscurity to swim with the big fish. So how did a boy from Stafford State School in Brisbane’s inner north, having had a childhood “as Queensland as you can get”, become one of them?

Nilsson’s eyes crinkle as freckles dance across his nose. “Well,” he grins, “I can’t say it was easy.”

Gordon Park, northside Brisbane, 1970s; in the shade of a sprawling mango tree, the Nilsson boys - Bob, Gary, Ronald, and David, the youngest - are pitching curve balls and sliders in the back yard, as their father, Tim, watches on. In a town that’s all about the cricket and footy, the Nilsson family, including mum Patricia and older sisters Jeannie and Susan, are an anomaly in their fascination for baseball.

There were few kids playing the game in Brisbane in the ’70s - and if they did, chances are they were introduced to it by the Nilsson clan. “We loved the cricket and the footy too, but we were absolutely obsessed with baseball,” Nilsson recalls. “That came from my dad [Tim Nilsson died last year, aged 74, while Patricia still lives on Brisbane’s northside].

He was a really good cricketer himself, but somehow along the way, and I’m not sure how, the baseball bug bit him. Of course we couldn’t watch it, as television certainly didn’t show it, so we played it, a lot.”

At first it was just the Nilsson boys loading the bases in the back yard, but they soon managed to rope in some schoolmates.

For David, at first it was just all about wanting to play with his older brothers, but before too long, he laughs, “I wanted to beat them. I really credit a lot of my success to them because you had to keep up with them, you had to be competitive, there was no slack cut because you were younger, or smaller. I think they made me a competitor.”

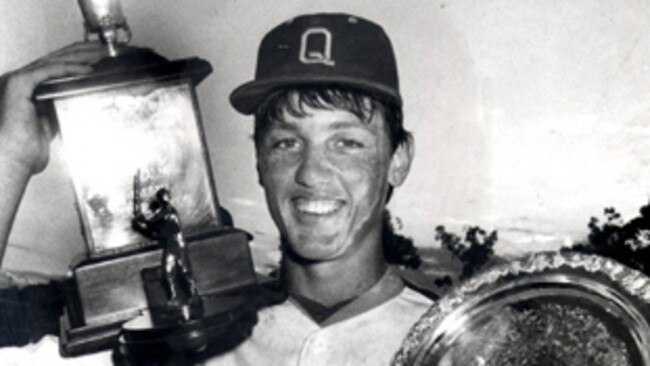

The Nilsson brothers began seeking out and playing for the few baseball clubs around at the time in Brisbane, some of which no longer exist – Tennyson, Stafford, Valleys, Everton Park – and it soon became obvious that the youngest had something special. At age nine, he made the under-13 state team, at 16 moving to the seniors to play the 18-plus Claxton Shield, Australian Baseball League’s version of the State of Origin. He was named Rookie of the Year for the ’86/’87season.

And then, like a scene from a baseball movie, two scouts – one from Oakland Athletics, the other from Milwaukee Brewers – started hearing tales of a talented kid from faraway Queensland, Australia, and both began courting a then 17-year-old Nilsson to join their club’s minor leagues.

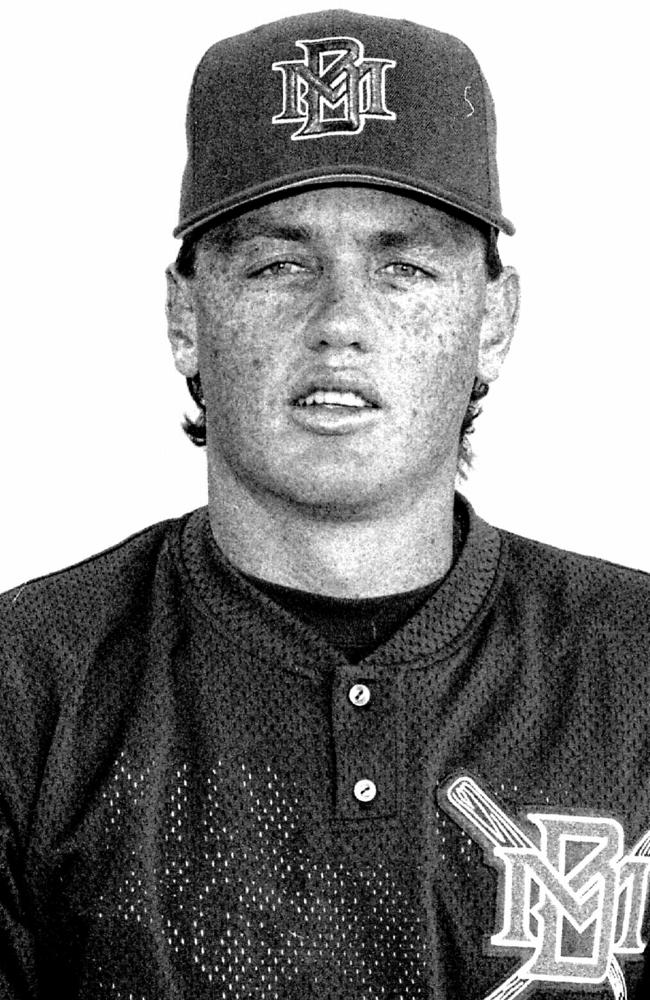

In January of 1987, at a pub in Wickham Terrace, Brisbane, the tall, shy teenager inked his name on a six-year contract with Milwaukee Brewers. His father Tim was there as a witness, Nilsson being too young to be in a hotel by himself but old enough to sign a deal that would take him far away from his family and into the very heart of American baseball.

Baseball is a hungry beast, where almost every day is game day. During the MLB season, teams play 162 games over 182 days, and to get there, Nilsson muses, it’s all about survival.

Minor League players, rookies, selected from all over the world, first attend training camps for their clubs scattered across the US, and are then assigned their minor league teams. In 1988, Nilsson was sent to Helena, Montana, along with five other Brewers rookies. They’d play ball all day, every day, Nilsson says, inching their way towards the big time. “It was survival, sink or swim, but I loved every second of it. I was 17, living away from home with no chaperone, living, breathing and sleeping baseball - for me, a dream come true. But you have to be single-minded about it, you have to prove that you’re better than the next guy, so that they should choose you.” For four years, Nilsson - slowly, steadily, but always with his eye on the prize - worked his way up through baseball’s ranks, from rookie league to “Single A” in Wisconsin, then California, “Double A” in Texas, “Triple A” in Colorado and finally, in 1992, the big time. At age 22 he was named catcher for the Milwaukee Brewers, which was, he recalls in his understated way, “quite a big deal, I guess”.

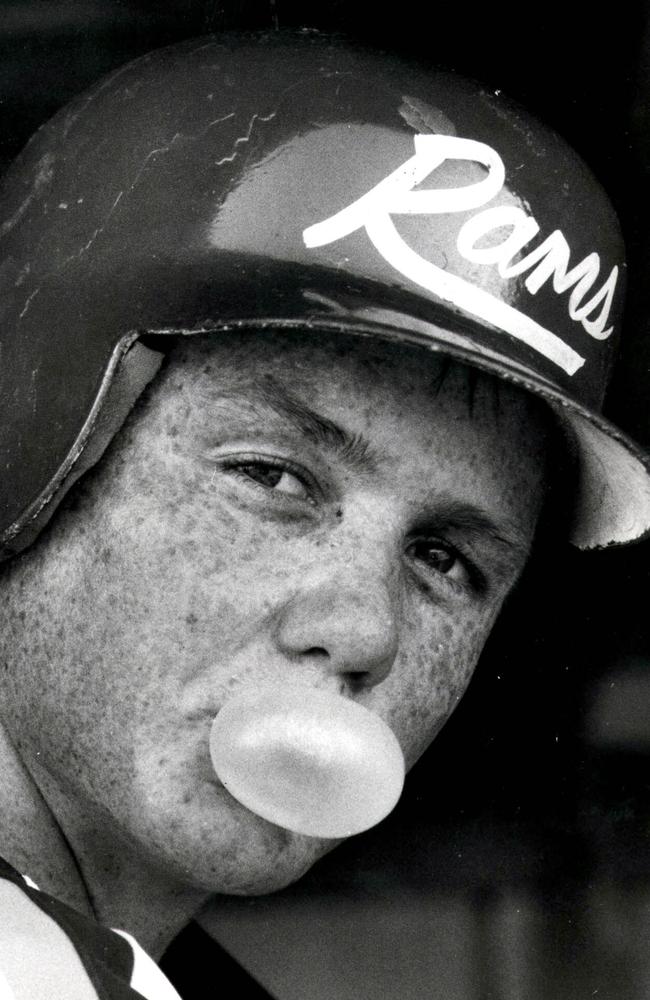

The catcher of a baseball team is its heart, the player who dictates to the pitcher what to throw, sets the field defences and calls the tactics, and the role is also considered the most physically demanding.

Which is perhaps why the most remarkable thing about Nilsson is that when the American baseball season, from April to October, finished for the year, he packed up his kit and came home to play ball.

“These days the MLB wouldn’t let you do it,” Nilsson muses, given how physically demanding the US season is, but I just felt really strongly I had something to contribute to the game in Australia.

I was the only guy over there doing it, so I figured I should come back here and try to help out.” While Nilsson underplays his role during those years playing for Brisbane Bandits and Waverley Reds, according to Queensland radio identity, baseball fanatic and Baseball Queensland board member Paul Campion, “it was a bit like Don Bradman coming back to play for Bowral”.

“It was a big thing for him to do; he certainly didn’t need the money, he did it for the love of it,” Campion says. “The truth is, I don’t think David has ever been given the recognition he deserves for his contribution to baseball in this country.” Australian Baseball Federation chief executive officer Brett Pickett calls Nilsson “easily the most prolific and successful international player this country has ever produced”. “Had he been that good in one of the more popular sports here, he’d have come home an absolute rock star.”

Nilsson played his last ball game after the 2004 Olympics where, as captain, he led the Australian team to a silver medal. His exit from the game was not as he would have liked it, coming as it did rather abruptly, and for all sorts of reasons. He left, it was said, because he blew his chances in the MLB after taking time out to lead Australia in not one, but two successive Olympic Games; because he didn’t get the deal he wanted with the Red Sox or Yankees after his Brewers contract expired; because his subsequent season in Japan was marked by disappointment on both sides; because he wanted to come home to Australia permanently; because he was burnt out.

The truth, he says, as in all good sports stories, is “somewhere in the middle of all of those things”.

“I probably had six or seven good years left in me, and there are those who still can’t believe I walked. The best way I can describe it is that when I left the Brewers, there were so many stories about where I was going and what I was doing, I just wanted to step away from the madness for a while.

“The thing is, once I stepped off the merry-goround, I found I couldn’t get back on. The years had taken their toll, physically and mentally, and I just couldn’t turn the switch back on.” While Nilsson laughs that he is in “no danger whatsoever” of being mobbed in the streets, the same can’t be said of his appearances at Brisbane baseball games, where kids regularly stop him for autographs and photos.

These days he’s Brisbane Bandits’ chairman, their just-named coach and international ambassador for Baseball Queensland. Nilsson has also launched the Dingo International Junior World Series to take place in Brisbane next year, featuring the best under-14 players from the US, Australia and Japan. And along with his siblings, he’s still running Dingo Print, the family business since 1959, while bringing up his own kids, watching them pitch curve balls and sliders in the back yard, coming full circle, making his own home run.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

How this unlikely ‘surrogate father’ found himself in the Hornet’s corner

Despite having no prior background in boxing or sports management, entrepreneur Phil Murphy funded Jeff Horn and another boxer. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS

Rebel rocker to working for the man: Is J.C. superstar a sellout?

What would John “J.C.” Collins’ younger self think of his modern role commissioned by the state government? The local legend hazards a guess. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS