LONG before the Gold Coast surrendered to the urban sprawl, it was a place of innocent wonder — all about surf, sand and ... flesh.

And at the end of every year, like a family of tired migratory birds, we headed south.

We packed the station wagon to the gills, shoe-horning ourselves in around folded tents and gas bottles and Skim boards and fishing rods, travelled out of Brisbane down the highway, passed the pie stand, stopped at the traffic lights near the lone palm tree facing the Broadwater at Labrador on the Gold Coast after what seemed an eternity in the oven of the car, then limped further south past the fancy motels and restaurants and the ice factory and into our destination — a grass and gravel patch of earth facing the sea.

This was Rudd Park, a camping ground tucked into the shoulder of Burleigh Headland. It was named after long-forgotten local councillor Gough Rudd, on the site of an indigenous recreational ground, used for thousands of years until we turned up with our Viscount vans and banana lounges. Here, local tribes had feasted and holidayed, their middens of oyster shells not far from our dented tin Eskies and portable gas burner stoves.

In Rudd Park, living cheek by jowl, were the people who couldn’t afford a holiday in the Kinkabool, El Dorado or the Mayfair hotels and motels, and ate at rickety fold-out tables and not in the Hibiscus restaurant or the Chevron in Surfers Paradise.

Here, on the Gold Coast, half of Brisbane rested after a long year of work and school. If southeast Queensland were a body, Brisbane was the brain and the Gold Coast a cluster of erogenous zones largely below the waist. It was a place to let off steam and have a play.

Sydney-based writer Frank Moorhouse has said the Gold Coast was the place where “I went to have nervous breakdowns”.

“I would know I was having a collapse when I found myself bursting into tears at the sight of a youth orchestra playing on television or when I saw the cranes flying north ... ” he wrote. “Maybe I saw the Gold Coast itself as a sort of urban nervous collapse — because, as a city of holidaymakers it was a city of people exhausted from a year’s work, on the edge, worn out, recovering; it was a city which understood nervous breakdowns.”

It was, too, from the 1960s, a landscape where at a certain time of year huge volumes of people wore very little clothing. It was the only place I ever saw the skin of elderly relatives, or my parents for that matter, other than their faces and forearms. It was a place of flesh, where the full panoply of the shapes and sizes of one’s fellow Australians — muscle, folds, spheres, ribs, curves, stretch marks, scars — could be seen on public display.

Indeed, before I was born, my mother had been a beach beauty queen at Burleigh, and dressed only in her one-piece swimsuit had her photograph taken sitting atop a lifesaver’s reel. So love had been in the air here, for my parents, in the shadow of the huge pine trees along the Burleigh Esplanade.

As Moorhouse further reflected: “The Gold Coast was seen by Australians as the most hedonistic of the Australian cities, devoted to the basic pleasures — sun, sand, shopping, steak, seafood, drugs, nightclubs, and alcohol. And real estate.”

A night out at Rudd Park in the 1960s was fish and chips and a spin of the Ambulance Station lucky wheel. Or a film in the nearby Deluxe Theatre, your skin blistering from the day’s sun in the cool light of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. But it was the beach that anchored us, and the music of the surf that lulled us, its melody creeping through the mosquito mesh and under the canvas flaps of the tent at night, carrying everyone into sleep.

And all the while — who could’ve known? — amateur photographer and social historian Graham Burstow was lurking among us tired urban birds with his camera, taking photographs that only now, after what seemed like just yesterday, have taken on the hue of nostalgia. Based in Toowoomba, he had come to Surfers Paradise on holidays as a boy from the 1930s to “feel sun on flesh”. Then in the 1950s, his father secured a piece of paradise — a block of land at Mermaid Beach — and built a fibro shack. His own tradition of Christmas vacations began.

Burstow, an engineer who later worked for decades in the family’s commercial floor-covering business, used the annual coast break to indulge his passion for photography.

He had been interested in the art since the mid-1940s. His late wife, Elvie Parfitt, was a keen painter. On holidays with their children, they would religiously go to the beach in the mornings, then head into the Gold Coast hinterland to the swimming holes, and he would take pictures while Elsie brought out her watercolours. His early photographs were of landscapes. But on the coast — in the thick of holidaymakers — people became his subject.

“I’m not a big fella,” says Burstow, now 87. “I liked to get in close. People didn’t mind. If you were close, they could see you were not a threat and you could explain to them what you were doing. I never had any trouble.”

And on the Gold Coast, he found a lot of skin. “In keeping with the new social freedoms of the 1960s, women’s swimming costumes shrank and exposed flesh became part and parcel of the scene,” he says in the introduction to his latest book of photographs, Flesh: the Gold Coast in the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

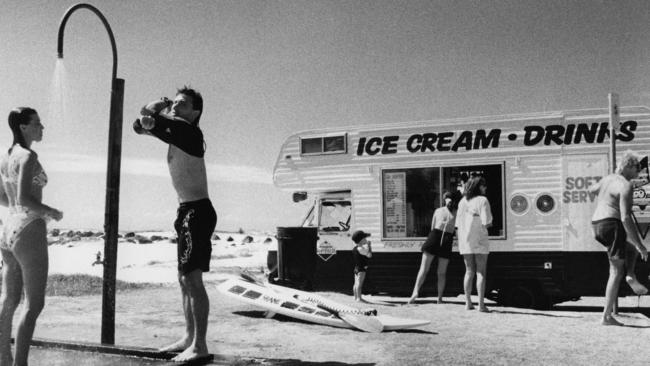

BURSTOW’S PICTURES ARE STARTLING IN THAT they depict an Australia that could now be seen as some sort of foreign country. You gaze at his beach shots, packed with sunbathers and swimmers a half- century ago, and they are striking in what they don’t contain — there are no fancy beach shades, mobile phones, Kindles, iPods or earphones.

The scenes are simply people being together in the sun, enjoying the water and being entertained by each other’s company. And by and large these Australians are physically thin. Demonstrably thin.

As for Burstow’s pictures from the 1970s, he has inadvertently caught a Gold Coast in transition. I would come to know this period on the coast intimately. Having made the annual Christmas/New Year pilgrimage for literally as long as I could remember, we moved there permanently in 1976 courtesy of my father’s work. After Brisbane, it was like settling on a strange planet. Everything was odd and discombobulating, given I’d always associated the Gold Coast with summer holidays. It was not a place where you put down roots. Tent pegs, maybe, but then they were packed up and gone after a few weeks. The Gold Coast, to me, had always been a place where you did nothing. How do you then live a normal, interactive life in a place of nothingness?

At the lunch bell at school, half the pupils would disappear. I found out soon enough that they’d hared down to the closest beach on their bicycles with boards under arms and fitted ina quick surf between mathematics and history.

Soon after I’d arrived, there was something of a scandal. Our geography teacher — a man so tanned he looked to be made of carved mahogany — was caught by police one weekend sunbathing nude up near The Spit, and arrested. He was living proof of my theory — how could you expect to carry on a conventional life with all its attendant responsibilities and all the while keep vacation-style recklessness at bay?

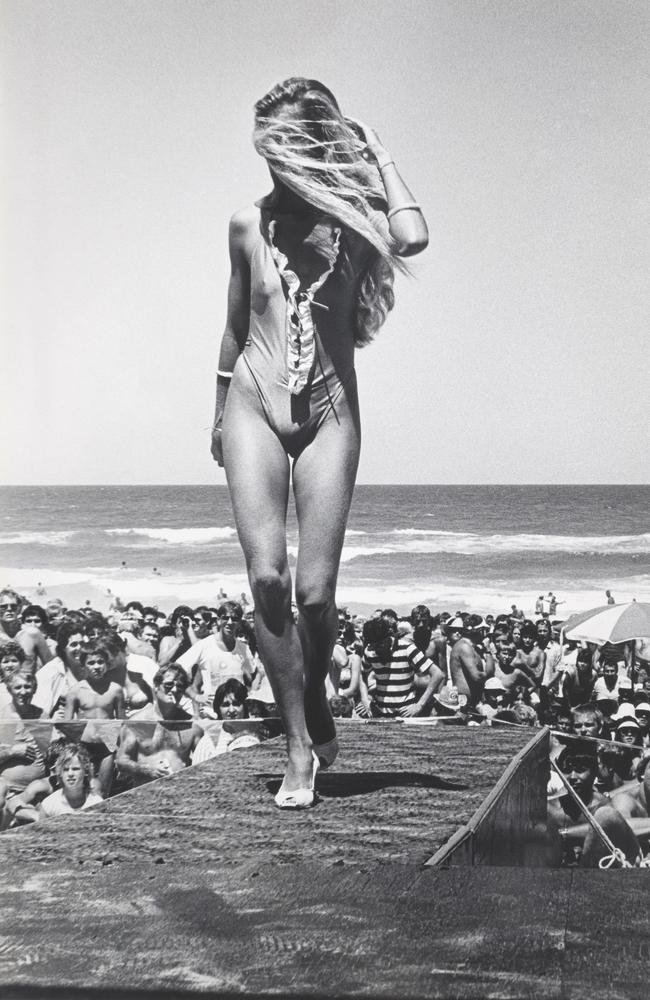

And if the place had been a shrine to beach culture and hedonism in the 1960s, it reached a new plane in the 1970s, and Burstow has captured the fake glamour, sexual tension and potential human anarchy of that. His photographs brim with bikini butt-cracks and the promise of flesh, with beach beauty contests and richly tanned skin. You see young women being sprayed as if they were duck breasts being basted for the oven. I recall my own sister, heading to the beach with a flock of girlfriends, and smearing herself with baby oil for an afternoon’s broiling. Like a good chef, she would ensure she turned herself over at regular intervals to secure an even bake.

You can see in Burstow’s young, scantily clad women — frozen in time — the early ravages of already too much exposure to the sun without any appropriate protection. They’re just a few short years away from deep, irreparable furrows, blotches and skin cancers. They look in danger.

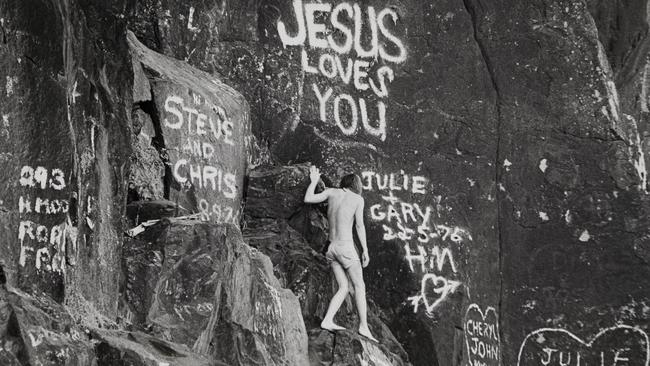

And this is one of the many beauties of Burstow’s work. His is a time when there was no such thing as political correctness, especially on the Gold Coast. Swimmers are sprayed with mutton fat by special beach vendors. Men are captured clutching beer cans. Cigarettes dangle from many lips. Litter carpets the ground. Graffiti on rocks at Currumbin reads JESUS LOVES YOU and JULIE, KEVIN / HONEYMOON, not the indecipherable gang badging, tagging and obscenities that cover public spaces today. An official at a beauty pageant in Surfers Paradise in the 1970s wears a T-shirt that proclaims: BEACH BOOB INSPECTOR.

Then there are the images of the coast’s annual beer belly competition. Men lugging boulders of frontal flesh that drop over the elastic of their Stubbies shorts; huge men, proud men. They clutch trophies, as chuffed as if they’d just won a Nobel Prize.

But this was the Gold Coast. Anarchic. Peculiar. Rebellious. Shocking. Free. As Professor Peter Spearritt writes in his introduction to Burstow’s book: “The Gold Coast captured here, with its local and southern bodies, has these days lost much of that informality. The closure of the railway line in 1964 produced a car-led linear urban form, where the ever-busy Gold Coast Highway cut the beachside off from the growing suburbs.

“The camping grounds from Coolangatta to Main Beach were whittled away over time to make way for new apartment developments ... Instead of wandering on to the beach from nearby camp grounds or fibro houses, holidaymakers had become consumers of real estate with views, some never leaving their own in-ground swimming pool ...

“Burstow’s photographs remind us of what many think of as a more innocent Australia, perhaps a less-knowing Australia.”

Near the end of the book is a handful of photographs that document that transition.

The pictures show the old beach shacks being demolished to give way to the skyscrapers. In the foreground, the airy homes that had witnessed thousands of happy family times are smashed, shattered, with concrete towers looming behind them. Priceless memories are simply removed with sledgehammers and a bulldozer. It is precisely the moment when the Gold Coast broke from its past and surrendered to the present. Some might say it did break, in more ways than one.

It has been many years since Burstow has been back to the Gold Coast. The last time he was there, he photographed yet another beauty pageant. But this time, to his shock, it was held indoors. This phenomenon left him scratching his head.

He estimates he has taken more than half a million pictures over his amateur photographic career. I ask him when he last took a picture. “Five days ago,” he says. “There’s a building going up in Toowoomba, behind a local church. I wanted to photograph that. It’s now taller than the spire of the church.” And he feels he no longer has to go to exotic locales to get good pictures. He has everything he needs at home. “There’s a group from India here today, doing a tug-of-war exhibition,” Burstow says. “The other day there was a big inter-schools football competition. There are outdoor coffee shops everywhere. You can go and get a photograph wherever you are. You don’t have to go anywhere. It’s all here.”

The final picture in Flesh is a poignant one. It shows a line of 21 girls competing in The Sunday Mail Sun Girl Quest on the Gold Coast in 1952. Only one wears a bikini. The rest are in one-piece swimsuits. Fourth from the left is a small, pretty, short-haired young woman. It is Elvie. She would marry Burstow three years later. My own mother would compete in the same Sun Girl Quest a half-dozen years later, and go on to marry my father.

It is Graham Burstow’s past. It is my past. It is our past. And in the click of a shutter, it’s gone.

Flesh: The Gold Coast in the 1960s, 70s and 80s by Graham Burstow (UQP, $25).

Exhibition at Brisbane Powerhouse, Oct. 4-Nov 2. brisbanepowerhouse.org/events

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Unmasking Qld’s cocaine dealers and their fallen empires

Cocaine continues to plague Queensland, but some empires have already crumbled. SEE THE LIST

‘It’s a big thing’: The fear that haunts Trevor Gillmeister

At age 61, nearly 30 years after his last game, it’s so far, so good. for Trevor Gillmeister. But that doesn’t mean he’s not haunted by what may still come.