ROCKS. Reefs. Sandbars. These are the pieces of the South China Sea at the epicentre of a growing stoush as the US moves to counter an increasingly assertive China.

HOW can the fate of the world hang on a few specks on a map?

Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan and China all want them. Or at least the resources they entail.

Their claims are overlapping.

Their historical and legal precedents are confused.

Their differences are intractable.

It has produced a hotbed of contention that is rapidly raising the risk of conflict and instability in South East Asia.

But there’s nothing fundamentally new about this dispute. It’s been simmering away under the surface in some form or another for decades.

So what’s changed?

China.

Now the world’s largest economy, it sees itself as a major player on the world stage. It has enormous outgoing trade and equally substantial imports of vital fuels and resources.

It wants to protect these. Cement them within its growing sphere of influence.

The United States didn’t get involved in the South China Sea dispute until 1995 when it issued its first policy statement on the matter. Even then it was only due to ongoing concerns raised by its long-term ally and former protectorate, The Philippines.

The US has in the past displayed its disinterest in the region by taking no position on the historical or legal merits of any claim.

So what’s changed?

China.

It is anxious to impose itself on the international scene, and is both strong and confident enough to assert blanket claims over the region. To do this it is building bases and stepping up military patrols in the East and South China Seas.

This has the United States worried.

Thus the “pivot to Asia” — a somewhat belated move by the US to show its commitment to the status quo.

But more of the same is the last thing China wants.

The upshot is a potential for escalation and conflict that has the region rapidly rearming.

What’s so important about a few rocks?

Oil. Gas. Fish.

All are dwindling resources vital for Asia’s surging economies.

Who can demonstrate ownership of a particular rock in the South China Sea gets the benefits of an “Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)” – an internationally agreed 12 miles (19km) radius of seabed which becomes the private property of that state. For a fully-fledged island, this explodes outward to a 200 mile (320km) limit — unless that waterway is within the EEZ zone of a nation’s primary land mass.

Then there’s strategic value.

A few of these outcrops have the potential to be enhanced. Expanded. Essentially, engineered into islands large enough to house an airfield, barracks and port facilities.

Not only does this boost the EEZ radius from 19km to 320km, it also provides the opportunity to project military power. From such island fortresses a nation could exert influence — if not outright control — over the immense commercial shipping traffic that passes through the waterways of the South China Sea.

These shipping lanes, perhaps even more so than the stocks of oil and fish, are of vital importance to every nation in the area — as well as their major trading partners, such as the United States and Australia.

This is what’s happening now in three core areas: Scarborough Shoal, the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands.

This is what has the United States, and the rest of South East Asia, concerned.

Ancient empire

China argues that historic exploration expeditions, its traditional fishing activities and past naval actions dating back centuries all establish a precedent for its modern presence in these disputed waters.

But this interpretation of history is itself disputed.

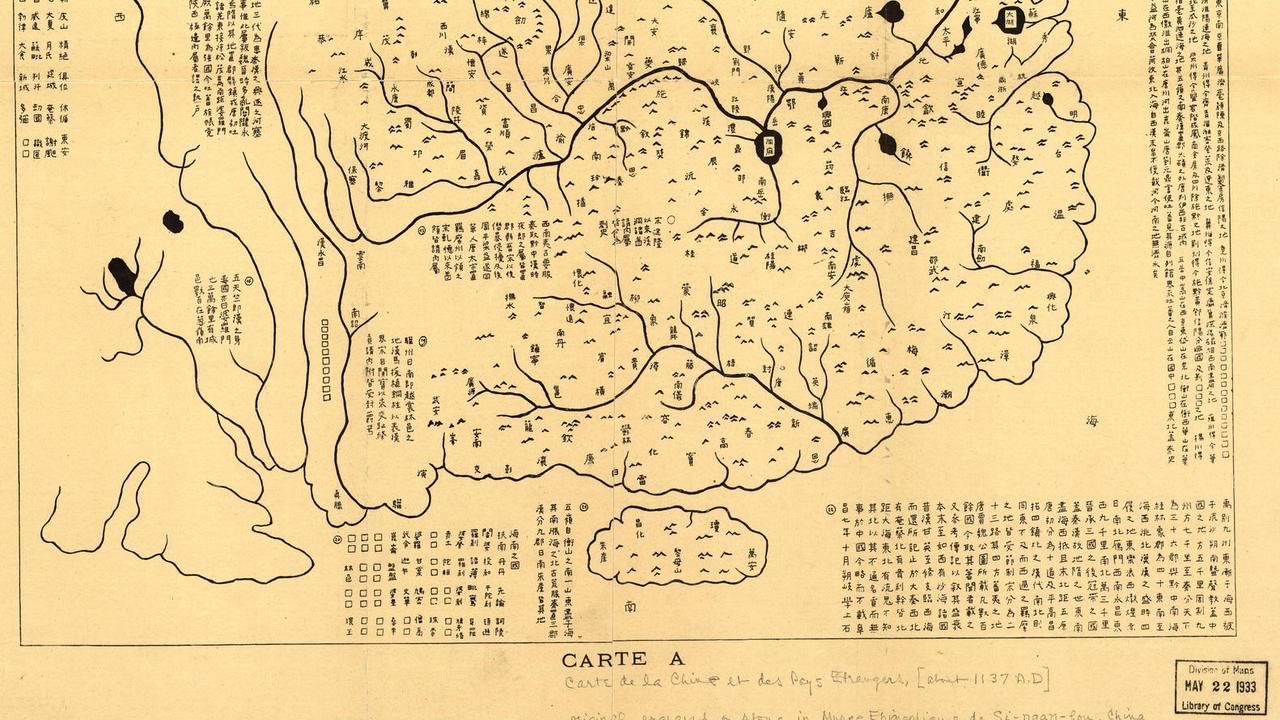

An engraving made in 1136AD shows the extent of what was even at that time a legendary Chinese empire — that described in the epic Yu Gong, a narrative history believed to have been written as early as the 5th Century.

It is but one piece in China’s convoluted argument. Alone, this map shows China’s borders ending at the island of Hainan — a large land mass off the coast of Vietnam, well before the South China Sea.

But the disputed islands do rate a few mentions in ancient writings, if not maps. China regards this as enough evidence for it to assert they were there first — and therefore own them.

To prove it, China has just launched a specialised “archeology” research ship to scour the South China Sea for evidence of Chinese occupation.

The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Japan — like Palestine — reject the validity of this ancient occupation argument.

It is also something of an embarrassment that the first modern claim to the South China Sea — specifically Scarborough Shoal and Spratly Islands — was made only in 1935, and even then they used their western names. Scarborough Shoal only received a Chinese name in 1947.

Nevertheless, China’s claim of “historic rites” has been embodied in what has become known as the “nine-dash line”. It’s a mark that appears on every Chinese map of the South China Sea since it formalised its claim with the United Nations in 2009.

Within its embrace is more than 80 per cent of the waterway — slicing through the Economic Exclusion Zones of other nations without regard to the international Law of the Sea.

China continues to insist the validity of these claims, believing it legitimises its sovereignty over the fish, fuel and mineral stocks there.

And it has since proven to be much more than just a line on a map. China’s actions now show it is quite serious about seizing and controlling this space, its sea-lanes and its resources.

Resurgent nationalism

The ancient empire is renewed. The glorious China of the past is being restored.

With it comes renewed passion in upholding what is stated to be “ancient” territory — no matter how old those claims may actually be.

It is all part of an upwelling of national pride.

What makes such clams suspect is that these reefs, shoals and sandbanks have mostly been uninhabited. Sovereignty usually entails occupation.

China realises this.

Thus the island-building campaign: Possession is nine tenths of the law.

Conversely, the world’s policeman — the United States — is feeling somewhat miffed. It is massively in debt — to China — and is struggling to maintain its overwhelming military might.

By no means has the international dominance of the US collapsed. But there is little doubt it is on the wane as increasing budget pressures on one hand — and enormous commercial cost blowouts and delays on the other — put the squeeze on the size and effectiveness of its military.

The significance of this struggle is not lost on China. After all, the United States won the Cold War through forcing the USSR into an economic arms race it could never win. Will the US now fall victim to its own tactics?

But that’s a long-term issue.

Right now China is keen to adopt an international role and assert a philosophy of “active defence”.

It is something of an amateur on the world stage.

Its expanding economic and military influence opens it up to the same accusations of imperialism it so readily casts at others. Its past emphasis on political neutrality will fray as it seeks to protect its growing interests.

Finding the right balance may prove painful, as scenarios such as the East and South China Seas continue to play out.

But what is certain is that China now feels strong enough, proud enough and confident enough to give it a go.

Modern China in the South China Sea

One of Communist China’s first acts of assertion over the South China Sea came in 1974 when it seized control of the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam in 1974. The United States, already weary of its long involvement in Vietnam’s internal conflicts, turned a blind eye.

Vietnam still maintains ownership of the islands. But China is not likely to leave.

For decades ownership of the shoals and reefs continued to be contested quietly by fishing fleets and occasional Coast Guard patrol craft.

China’s actions were peaceful, but assertive. Each small incursion — while not enough to provoke a military response — was maintained. Slowly but surely, China’s interests were deeply ensconced. By the time rival claimants realised the significance of each act, the opportunity to oppose it was lost.

In 2011, A Chinese fishing boat cut cables from a Vietnamese oil exploration vessel. In 2012 eight Chinese fishing vessels were involved in a two-month standoff over what The Philippines called illegal fishing. In retaliation, China effectively seized control of Scarborough Shoal.

The Philippines protested. China refused to relent.

The United States, despite a few formal protests, did nothing.

This leaves only one element of the “nine dash line” not fully under Chinese influence. Yet.

The Spratly Islands.

This is where recent tensions have been centred.

Where we are at

It was not until 2010 that the United States started to show serious interest in China’s growing South China Sea ambitions.

President Barack Obama established the region’s security as a new priority.

It’s since enhanced diplomatic and military ties with Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and The Philippines. It has also been openly raising the question of ownership with China itself — asserting its belief that any nation has the freedom to exploit and protect their UN defined Economic Exclusion Zone.

Amid all this came a shift in US military strategy: It enacted a “pivot” to Asia.

Essentially, this meant a repositioning of a significant portion of its fleet and air force to bases in the region.

It sends a clear signal to China: We’re here. We’re watching you.

In May, the United States declared its intention to assert “freedom of navigation” over the South China Sea to preserve its openness for international trade.

This includes the freedom of military forces to conduct surveillance and patrols in these international waters.

It has since deployed the first of these ‘patrols’ - sending the destroyer USS Lassen into contested waters.

China has responded with affront.

It sent its first signal that it would not accept such ongoing openness back in 2009 when its fishing fleet and a People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) frigate engaged in aggressive manoeuvres intended to force the US Navy survey vessel Impeccable away from the Paracel Islands.

In November 2013 China asserted control over another nearby waterway previously considered open: It declared an “Air Defence Identification Zone” in the East China Sea — a region which encapsulated islands of disputed ownership between China, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea.

Some strategic analysts fear such a declaration will soon be imposed upon the South China Sea: Especially as China has demonstrated its determination to establish control over the air and water way by engaging in dangerously close air intercepts of US patrol aircraft.

Any such declaration will undoubtedly result in yet another escalation of tension, posturing and diplomatic wrangling.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As summer sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.