JOHN Tyson is standing not far from a row of ancient willows that borders the canal that is East Creek in Toowoomba city, 127km west of Brisbane, and as a breeze shifts the trees’ long green braids, he’s taken back in time.

Tyson, as a boy, spent every spare minute in and around the creek. He grew up in nearby Mackenzie St, directly across from the old watercourse, and he played here, trawled for yabbies, and dreamed.

When the rains came, he and his mate, Paul “Keads” Keating, would dash over to the nearby East Creek service station, grab some tyre tubes, and propel themselves down the rapids, launching out from the intersection of James and Kitchener streets. Or, when the creek truly flooded — as it had done following heavy rains for millennia — he and Keads would secure ropes just above the water level between the willows, jump in upstream and grab the ropes as the water fired them west.

Today, Tyson shudders at the thought of his childhood derring-do. If he’d missed those willow ropes just once, they’d be fishing his body out downstream, maybe as far away as the famous Mother’s Memorial in East Creek Park — an 8m column unveiled in 1922, and erected by Toowoomba mothers whose sons didn’t return from the Great War.

Often, it could have been a memorial of sorts to the daredevil Tyson.

“We played in the creek all the time,” he recalls.

“When we were young we made our own fun. In Toowoomba, we weren’t near the beach. We had a pool. But the creek … ”

Both East and West creeks in the southern part of the city are primary tributaries that join Gowrie Creek north of the CBD, the three effectively draining Toowoomba. And while Tyson might have had a few near-misses during flooding events in his boyhood, the drama that has played out at the intersection of James and Kitchener has been tragically familiar for generations.

In 1893, a “pitiless deluge” inundated the “Garden City”, a wall of water passing over the James Street Bridge and flooding city streets, taking with it a man named James Kiley, whose body was later found with one arm fixed “straight up … as if in the act of catching some support”, according to the local press.

Then in April 1906, a hailstorm later described as a “miniature inferno” bore down on Toowoomba, killing livestock and striking birds from the sky.

The Queensland Times reported that the “unfortunate Chinamen who cultivate the portion of land at the junction of James Street and East Creek” witnessed the decimation of their four-hectare crops.

A similar event occurred in February 1926, hitting a group of “foreigners” camped at the notorious intersection. Again, exactly one year later, heavy rain flooded the James Street Bridge over East Creek.

“The willows along the railway gave a picturesque effect to the rushing waters,” reported the Brisbane Courier.

Then in 1931, following torrential rain, a wall of water travelled down East Creek with such force that it swept away horses and poultry, overturned water tanks, and hit a furniture shop, sending tables and chairs down towards Gowrie Creek.

One of the proprietors said the situation went from normal to catastrophic “within two minutes”.

This would have been dry history to John Tyson, 50, if he and his family had not become a tragic, permanent part of it.

Tyson looks beyond the willows to the traffic lights at the intersection of James and Kitchener. Tied to one of the lights is a handwritten sign — RIP Jordan Rice. It was here, four years ago, that Tyson lost his partner, Donna Rice, and their young son to the raging “inland instant tsunami” that hit Toowoomba on January 10, 2011.

Just as witnesses for more than a century had described the phenomenon of flooding at East Creek during heavy rainfall — normal to catastrophic in minutes — so too Donna, 43, and Jordan, 13, fell victim to an identical deadly weather event.

Both were swept from their vehicle by a raging torrent, and not before youngest son Blake, 10, also in the car that day, had been rescued at the urging of Jordan. “Take my brother first”.

They would discover his hero brother’s body downstream later that day, not far from the first place Tyson and Donna moved into together as a young couple in the early 1990s.

“They found his body wedged in the fig tree near the Mother’s Memorial,” Tyson says.

“That was a bit ironic … back to the start.”

Tyson stands quietly near the hissing willows and stares in the direction of the creek. His face, taut and straightforward, bears a shadow of deep hurt, as if it might require actual physical effort for him to find something amusing, or to respond to anything without gravitas.

It is sunny, warm, and the creek is a trickle. He could not have known that this place, his boyhood idyll, would in the distant future claim members of his tight-knit family.

Nor could he have known that that one deadly moment, at 1.45pm on Monday, January 10, 2011, would, over four years, scour his life back to nothing.

In 1981, Tyson, just 16 and two year into his apprenticeship as a plasterer and renderer, was kicking around with a mate outside Red Rose Cafe in Ruthven St, Toowoomba, when a 14-year-old schoolgirl called Donna Rice caught his eye.

“Check this out,” Tyson said to his friend. “Here comes my future wife.”

“You’re kidding, aren’t you?” the mate joked. “You’re dreaming.”

As she walked past, Tyson grabbed her by the hand and spun her around.

“She gave me a big gobful of cheek and off she went,” he remembers.

“I made it my business to really get to know her. I found out about her. I just literally went on a seek-and-search mission. To me, she had something about her, you know? She had a warm, gentle glow. And that’s the way she was.”

Rice, too, was born and bred in Toowoomba. And while there were plenty of other girls in town, to Tyson, “she was the one”.

Several years after that impromptu street waltz, the couple moved into a house near the Mother’s Memorial, just a dozen streets from the intersection of James and Kitchener.

Tyson had established his own businesses — cement rendering, and an international shipping company — and Donna helped out on the financial and administrative side.

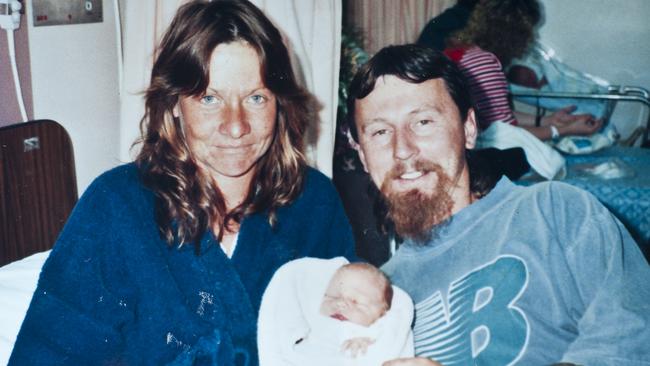

And they started a family. First came Christopher, now 26, followed by Kyle, 20, Jordan (who would now be 17) and finally Blake, 15.

The couple never married. Tyson says: “I’m not very fussed with any of that sort of stuff, and she used to say to me it’s only a piece of paper, it doesn’t really matter. To tell you the truth we’re both pretty shy people, and I guess having a wedding and having the spotlight shined on you wasn’t very high on our list of priorities. It wasn’t really us.”

As the family expanded, they moved to a house on about 4000 sqm at 17 Vanity St, near Wilsonton in Toowoomba’s north, not far from Gowrie Creek. Tyson levelled out a portion of the yard where the boys could play sport, ride dirt bikes and explore to their hearts’ content.

“Like every parent, they’re the happiest days of your life,” he recalls.

“We were the epitome of the Australian family, with four boys … it was football and cricket all the time, it’s all they ever did. We had a ball.”

Like father like son, Jordan would go yabbying with a cousin in nearby creeks and tributaries, bringing in his haul with a makeshift net of stockings and coathangers.

Donna, too, went about keeping together her large family. A workaholic, she cooked, cleaned, organised the children (and most times her partner, John, too) and essentially steered the ship.

By late 2010, however, months of incessant rain had impacted on Tyson’s plastering and cement rendering business.

“Because it had rained for nearly three months, and because all of my work was outside, I literally hadn’t worked for ages,” he says.

“I’d go and try and do a bit and it’d get washed off. I spent a lot of time with Donna. It was good.”

Occasionally, on those rainy days, Tyson and Donna snuck off to Brisbane without the children knowing, and had a big steak lunch at their favourite watering hole — the Norman Hotel at Woolloongabba.

As December moved into a sodden January, Donna turned her thoughts to the new year.

Jordan was about to start high school. He was a shy boy. He had the physique of an athlete, but preferred the arts, particularly dancing. Jordan just loved to dance.

On the morning of January 10, Tyson and Rice did as they had always done — both got up around 4am, and sat together at the kitchen table, she drinking coffee, he a cup of tea.

It was how they started their day, with some quiet time together before dawn.

Everybody was home that day, except for Chris, who had moved into his own digs across town.

“It was just like normal, but rain, rain, rain, constantly,” Tyson says.

“We pondered the day. We basically planned to go down and get Jordan’s uniform for high school. I said we’d go down and get that done early, and then we’d have a muck-around and get a bit of lunch on the way home.”

Jordan didn’t make the trip that morning but stayed at Vanity St.

Meanwhile, Tyson and Rice picked up some fish and chips for a family lunch.

When they got back to the house, Jordan told his parents that Chris had been ringing constantly. He needed someone to pick him up and take him in to the CBD to sign some credit card application papers. It was about 1.30pm.

“Typical her, Donna just dropped everything and took off to go and do that, and I said, ‘Just wait, sit down and eat your lunch and we’ll all go’, and she said, ‘No, no, it’s alright, I’ll go’,” Tyson recalls.

“And Blake and Jordan went with her. Off they went. They [the boys] had the typical fight over the front seat. Blake won that. They were on their way to Chris’s place. He was up in the Rangeville area. He was on the southeast, and we were in the northwest [diagonally across the other side of the city]. He didn’t have a car.”

En route, Donna grew alarmed at the rising water along North St, as she made her way in her Mercedes towards the intersection of James and Kitchener.

She stopped the car at one point and told the boys: “I’m not going to go. I think I’ll turn around and go home.”

But Jordan was insistent.

“Keep going,” he told her. “Don’t be such a pussy.”

Donna was two vehicle-lengths back from the traffic lights at the intersection. She had her foot firmly on the brake. She hesitated. Then the water rose around the vehicle at an astonishing speed.

Two civilians attempted to save the family. Blake was pulled free, but Donna and Jordan were sucked into the roaring water to their deaths. They had only been gone from home for about 25 minutes, their lunch still on the table in Vanity St.

Hours later, John Tyson was growing worried about the whereabouts of Donna and the boys.

He asked son Kyle to ring her on her mobile phone.

There was no response.

Then there was a knock on the back door. It was the police.

“Straightaway in my head I thought something’s happened, but I didn’t know what,” says Tyson.

“Anyway, she [a female officer] come in … and she motioned towards me. She asked me if Donna had any tattoos. About 18 months earlier she’d got a simple band of butterflies around one wrist and a band of flowers around the other; her two favourite things. [The police] didn’t have to say it but I knew exactly then, I thought … Donna’s dead.

“The police officer said, ‘She’s passed away, we found her body’. I asked about Jordan and they said he was still missing. I knew he was dead, too. Blake was in hospital. I said to Kyle, ‘Mate, we’ve got to go to the hospital. The police are here, we’ve got to go’.

“He said he wasn’t going anywhere. I said, ‘Mate, your mother’s just died’. He broke down. He started punching the walls. He ripped all the skin off his knuckles. I had to grab him in a bear hug and stop him. He was literally inconsolable.”

Up at Toowoomba Hospital in Pechey St, Blake was wrapped in a blanket, reeking of creek water.

“What happened?” his father asked him.

“We were just driving along, dad, and mum pulled up at the lights; then the water just came up and no-one would save us, they were all just looking at us, then two blokes come out and helped us,” Blake recounted.

“They tried to take Jordan first, dad, but he wouldn’t go. He made them save me and now he’s dead. I was in the front and they tried to drag [Jordan] out and he wouldn’t go and he grabbed me and pushed me through and made sure I went first. That’s how I got rescued.”

As they visited Blake in hospital, Jordan’s body was found in the tree — almost 2m above ground level — down near East Creek Park.

Blake returned home with his father to Vanity St that night.

Just a few hours earlier, they’d been a family. Suddenly they were incomplete.

The impact of the loss was immediate.

“Kyle had to surround himself with friends,” says Tyson.

“They’ll think … we feel your pain … they do, but it’s not the same pain. A lot of these boys … were having a good time. I said to Kyle, your mates have got to go, mate, it’s really starting to do my head in. We had a bit of an argument. I said I couldn’t put up with it. I basically showed my kid the door, which I really, really regret. He went and lived with a few friends but he was just house-hopping; then I couldn’t get him back. He was homeless.”

Then the harassment began.

Carloads of youths would pass the house in Vanity St, shouting abuse at Blake. The story of Blake and Jordan had gone global, and the surviving boy had become a lightning rod for attention.

This was followed soon after by prank calls, rifle shots fired at the house, and a malicious social media campaign against the family, culminating in a Facebook page titled We Bashed Blake Rice.

Family friend Tim Webber says the aftermath of the tragedy was a social disgrace.

“A lot of people were really cruel,” Webber says.

“They thought John was seeking attention, but John’s not one to ask for anything. A lot of people need to be held to account for what they’ve done, and importantly for what they haven’t done.

“In the army, people come back [from conflict] with post-traumatic stress disorder. If that had been John, he would have been given counselling for the rest of his life. Instead, he’s been ignored.”

Tyson was troubled at the growing animosity towards himself and his family in his own home town, and beyond. He’d been unwittingly thrown into the spotlight.

Now, peculiarly, he was paying the price for that.

“Do I end up reacting to what’s going on? I very nearly did,” says Tyson.

“That would have helped no-one. Blake would have ended up fatherless. I had people like white supremacists from America shoot me things on YouTube, mailing me pictures of a boy floating in the ocean with BUOY written under it … people saying, ‘I wish he was alive [because] I would have molested him’, and all this sort of crap.

“It did not stop. That’s why I had to pull down the RIP Jordan Rice Facebook thing. For all the good people on there … there were some beautiful tributes … from [musician] Leonard Cohen … some beautiful things were said, but unfortunately the bad element really destroyed it for me … I still regret having to pull that [Facebook page] down.”

Tyson also struggled with filling the void Donna had left.

“Basically, I’d never really been a cuddly father,” he says.

“I’m more let’s go up the shed and do some boxing. Here he is, I’ve got this kid [Blake] that hovered off his mother, and I’ve got to try and fill that breach, and I couldn’t.

“He’s wanting this personal loving. He wants someone to make him feel better. I really had to try and separate myself, and to this day I have. There are two Johns, the John that will break down and cry if he has to, and there’s the John who’ll switch everything off and go forward.”

Meanwhile, then Queensland premier Anna Bligh announced a royal commission into the floods.

In the interim, Tyson says Queensland Police asked him if he was interested — given his recent experiences — in participating in a revamp of the Triple Zero emergency system.

The system, as it stood, had monumentally failed the flood victims of January 2011. (The royal commission would reveal a string of flaws, and produce an astonishing transcript of Donna and Jordan’s two emergency calls to Triple Zero. Donna’s cry for help was not deemed a high priority, and Jordan’s frantic pleas shortly after came too late).

Tyson agreed to participate. It was also a distraction from his family tragedy.

As he wrote in a formal submission to the recent Select Committee into aspects of Queensland Government administration: “The more I thought about it the more passionate I became about the idea. I engaged the help of some friends and set about developing a computer system with app attached, that resolved quite a lot of the shortfalls of the emergency services and would aid search and rescue efforts.”

He poured time and money into the project, only to discover it was going nowhere.

“I now know I was merely being paid lip service and that there was never any intention of the government buying into a potentially life-saving initiative.”

With his money dwindling, Tyson refused to accept any compensation for his tragedy.

There were other people worse off than him. “My view was, if you want to help me, put it into the [Premier’s] Flood Fund,” he says.

“All of the funeral envelopes went into the Flood Fund. I thought I was doing the right thing.”

In the end, with Kyle gone, Tyson decided to move out of Toowoomba. So he took Blake to the only other place in the world to which he felt connected — the Gold Coast, where Tyson’s grandmother once lived, and where he occasionally sought “sanctuary” as a child.

He sold the property in Vanity St for a song. He abandoned his businesses. He left Donna and Jordan, buried in the same grave, in the Drayton and Toowoomba Cemetery on South St, and struck out for a fresh start.

Tyson and Blake settled in Robina, west of Broadbeach on the Gold Coast.

From the outset, the omens weren’t good. He bought a house, secured a large mortgage and tried to get his earnings back on track.

“I got a bridging loan,” he says. “My house in Toowoomba took a massive hit. I had to virtually give it away to get out of it.”

Relentless legal battles took their toll. First there were the findings of the police.

“I couldn’t have my wife go down in history … I think their exact words were: ‘who could possibly know what was going on in her mind when she knowingly drove into a flooded intersection? … ’

“That’s basically saying she was an idiot. ‘Yee ha, let’s go and kill all the kids’. To this day, there hasn’t been any media report on what actually happened on that day. People still believe my wife drove into a flooded intersection and killed herself. She was negligent. That’s still the belief. I was foisted into fights I didn’t want to have.”

According to Tyson, the initial police report into the incident blamed Donna.

“Conscious decisions were made by Donna Rice … to drive into flood waters, [the] behaviour was risk-taking as all the circumstances including what may have been operating [in her mind] at the time cannot be known with certainty,” the police concluded.

Tyson managed to have the police findings overturned.

Later, then state coroner Michael Barnes would find that Donna was not “reckless in her manner of driving; she stopped the car before the intersection in what was then very shallow water and waited to see whether it was safe to proceed. She could not be expected to have foreseen the rapid transformation of the scene that soon took over them”.

It was a victory for Tyson but he was mentally and financially spent.

Two years after the tragedy he found a new partner. They married and had a child together. He feared loneliness, but he hadn’t left the events of January 10, 2011, behind him. The relationship subsequently disintegrated.

“It was wrong for me to bring anyone into my world because it isn’t exactly easy,” he says now. “It was very, very hard on [his ex-wife]. I still have many battles to fight, and unfortunately they’ve got to be on my own. The time I spent with Donna were the best years of my life, they honestly were.”

As for Blake, he faced new rounds of torment on the coast.

Just as it was in Toowoomba, he was bullied at school until Tyson pulled him out.

As a way of trying to make ends meet, and to fulfil his ambition to help people who may, in the future, face a tragedy of the dimension that he had experienced, Tyson worked as a manual labourer during the day, then at night and on weekends developing flood- and fire-proof building systems.

He wanted to make homes that could withstand powerful floodwaters, and simply be hosed afterwards. Houses that could withstand heat of up to 700 degrees Celsius for up to two hours and still retain their structural integrity, in the event of a bushfire. Tyson wanted to save people. He wanted to protect families.

Longtime friend and partner in the disaster-resilient homes project, Edgar Lucht, of Gympie, says all Tyson has ever wanted to do was prevent other families from going through something similar to his own tragedy.

“He has to start his life over and he can’t because he’s got nothing to start it with,” Lucht says.

“He tries so hard to please others. He really deserves something better. Why don’t we look after our own here? It’s not such a big thing to get a guy going again. He’s a tradesman. He knows what he’s doing. The state government should be looking at his ideas. At least look at them. John Tyson is on his own out there.”

Friend Mike Kitzelmann, CEO of the Etheridge Shire Council in Far North Queensland, says the fact that Tyson was run out of Toowoomba because he pursued the truth about what happened to his wife and son on that tragic day was beyond belief.

“What he’s been through is horrendous,” Kitzelmann says.

“What happened on that day [January 10] was a complete failure. Failure happens. But you don’t hide the fact that it happened or put a different spin on it.

“Conspiracy might be too strong a word to use, but that’s what it appears to be. The entire fabric of that family has been destroyed. He’s a very intelligent man and he wants to do the right thing by the community at large. All he needs is a chance. Give the bloke a chance and you won’t be disappointed.”

Tyson says he has seen little of his oldest son, Chris, since the tragedy, and Kyle, after a series of incidents, is presently in Woodford prison. In May last year, Kyle Rice, then 19, was handed a jail sentence for killing a guinea pig. The Toowoomba Chronicle reported: “He was captured on video throwing one guinea pig into the footpath … before throwing the dead pet into a nearby yard”. His solicitor, David Burns, had told the court that Rice’s offending started after the flood tragedy involving Donna and Jordan. He was sentenced to three months’ jail but released on immediate parole and placed on two years’ probation.

A series of incidents saw him breach that parole and receive a custodial sentence. Tyson says his son was involved in a number of fights after January 10, and had suffered seizures. “I can tell he’s not the same kid, end of story,” he says. “He got right into methamphetamines. It’s heartbreaking, mate.”

Last year, having spent all of his available funds on the Triple Zero emergency system revamp, the safe homes project, legal fees and his mortgage for the home he has to sell, Tyson and Blake moved into a homeless shelter in Tugun on the Gold Coast.

In one week, his emergency stay at the shelter will be at an end, and his only alternative plan is to sleep rough.

Tyson says he has contemplated suicide.

“Even today I still have the odd thought,” he says.

“Stuff just mounts up. That’s not to say I ever will, but I think about it. Because I know she’s there and I’m here.”

In less than four years, his full life — a loving partner, lifelong mates in Toowoomba, volunteer work as a popular part-time football coach, race car enthusiast with four healthy sons, successful businesses and a place to call home — had travelled, like floodwater, down the range to the sea and emptied into nothing.

John Tyson is standing at the foot of the grave of his wife and son in the cemetery on South St, across town from the intersection of James and Kitchener Sts.

When he buried them just days after the tragedy, he made sure Donna got one of her last wishes. It was a secret between them.

“When we used to have our morning cups of tea she used to say, you know, I’m getting old,” John says.

“She’d always say, ‘I hope I die before you … but when I do you bury me ten years younger, you make sure of that’. She’d always be on about it.”

So that’s what he did. Instead of having her tombstone inscribed with her actual birth year, he added another decade.

“There she was, ten years younger,” he remembers. “That was the last thing I could do for her.”

But some of Donna’s relatives objected and the date on the stone was corrected. (QWeekend confirmed that the headstone had been redone, the work paid for by Donna’s relatives. At present, there is no law that allows immediate next of kin automatic propriety over a headstone and what appears on it, given potential conflict between family members, the wishes of the deceased’s estate, etcetera. It is deemed, in the stone masonry industry, a legal “grey zone”.)

Tyson says it was the final kick in the guts for him.

“I owe a lot to Blake, to protect him and guide him. I’ve only got (one week) left at the shelter. I’ll take up a crappy job. Fruit-picking. I don’t know. I have no idea at all. I want to help others through my experience. Ignorance can cost you your family’s life. Ignorance can be the difference between life and death.”

Tyson still has more questions about that unforgettable day than he has answers. He says that during the Queensland Floods Commission, presided over by judge Catherine Holmes, the issue of the multiple fatalities in Toowoomba, Murphy’s Creek and Grantham was not given the commensurate time to be thoroughly assessed.

Tyson wants the event reinvestigated with the full facts. He wants a forensic examination, down to the minute, of the whereabouts of all rescue, police and emergency workers on that day. He attests that on January 10 there were 800 “near misses”, just in Toowoomba, and that not a single rescue orchestrated on that day was carried out by emergency personnel, but by civilians.

And he wants the intersection of James and Kitchener and its history in relation to flood events to be examined after years of calls for it to be rightfully upgraded to meet its flood immunity predictions, as cited in reports released in the years leading up to the January 10 event.

As he wrote in his senate submission: “My motive … is to ensure that if a similar extreme rain event occurs in Toowoomba that measures are instigated to provide timely, effective warning to people and to improve rescue responses … I am [also] looking for acknowledgment and accountability from those who are directly, or indirectly, at least, in part responsible for the deaths of Donna and Jordan.

“The public need to know the truth as knowledge and strength in numbers will result in change, and in turn possibly save someone else’s family from suffering the same traumatic experience we have.”

Standing by the grave, Tyson looks down at the small pictures of his wife and his boy embedded in the headstone. The inscription reads in part: World’s Best Mum and Lion-Hearted Son. They are safe now and far enough away from East Creek to never be harmed again.

“I have so much to offer,” Tyson says, almost speaking to himself.

“I hope I can get on and forge a life and help a lot of people on my journey. But I have no way forward.”

Jordan Rice Foundation jordanricefoundation.com

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Secret deals of one of Qld’s most powerful people you’ve probably never heard of

He is arguably one of Queensland’s most influential people and this week turned a $925 investment into a $125,000 windfall. But there’s every chance you’ve never heard of him.

TV weatherman’s ‘career-ending’ out-of-body experience live on-air

Half a million Queenslanders watched Tony Auden’s tiny, innocuous cough during a weather bulletin, totally oblivious to fact it was signalling an “out-of-body experience” he was enduring that would see his world unravel.