Brisbane’s path to Olympic gold in 2032 could lay in the rubble from four decades earlier. SPECIAL REPORT

As a city we have been here before, albeit with a slightly more progressed model this time … maybe.

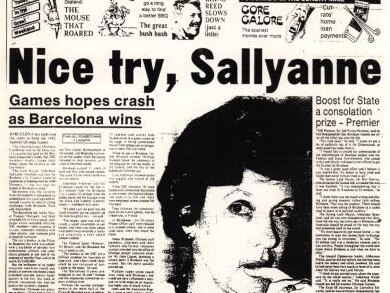

Queensland’s capital put its hand up for hosting rights to the 1992 Olympic Games – ultimately won by Barcelona – but finished third in voting in October 1986.

This time around, enshrined on June 10, 2021, Brisbane won IOC approval.

So what’s next?

That has been, and continues to be, the issue.

The best location for the main stadium – plus the size and cost – are now bigger battles than anything we will see at the Games.

Even the mascot remains a hot debate.

This is the tale of Brisbane’s twisted, bizarre and inspiring Games bid from decades earlier >>>

Early moves

New threat emerges

It started on October 15, 1982 when Brisbane Lord Mayor Roy Harvey confirmed he would investigate Brisbane hosting the 1992 Games.

That plan got a bump into the future on January 23, 1984 when the NSW Government was urged to go all-in for hosting rights.

Opposition Leader Nick Greiner insisted Sydney start planning a campaign to win the Games and to sound out private enterprise to play a major role.

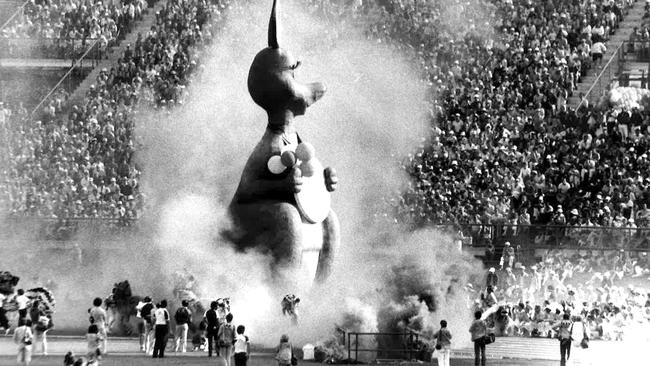

It proved a jolt for Brisbane, which was well advanced in preparing a case for staging the 1992 Games; it had sent a delegation to Los Angeles, the site of the 1984 Olympics, and had received the support of the Australian Olympic Committee and as well as the advantage of the experience of staging the 1982 Commonwealth Games.

“Sydney’s chances of staging the 1992 Games have to be very good – but only if the Government acts quickly,’’ Mr Greiner said.

Brisbane’s benefits

Stockholm, Paris, New Delhi and Barcelona were in the race – but Brisbane was deemed to have many advantages.

This included a complex plan in which all sports venues would be within 20kms of the Olympic Village, and less than 30 minutes travelling time.

Security was also a primary weapon, as well as the new international airport able to handle the 15,000 athletes and officials, 10,000 media representatives and 200,000 visitors.

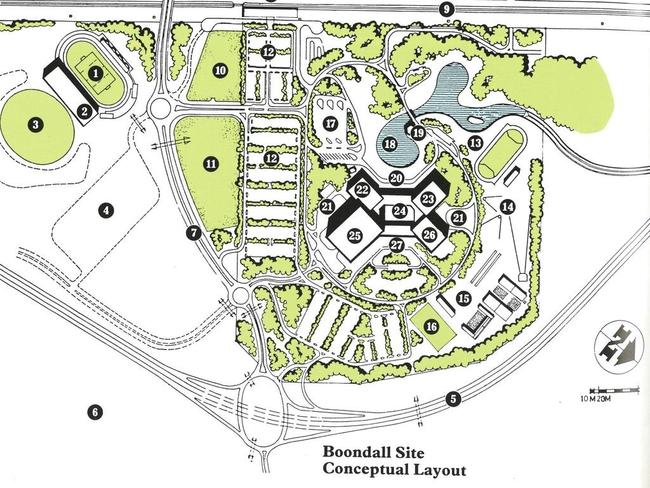

Planning documents showed the Brisbane Olympics was to be split into four zones: Central City Zone, Boondall Zone, Chandler Zone and Queen Elizabeth II Zone.

Nathan’s QEII Stadium was to host the opening ceremony, with capacity to be increased from 62,000 to 95,000.

The Games was expected to cost $821 million with an expected revenue of $908 million.

AOF support

By March 8, 1984 the Australian Olympic Federation came out in strong support of an expected Brisbane bid.

The federation secretary-general, Judy Patching, said in Melbourne he had not the slightest doubt Brisbane could stage the Games successfully.

Queensland Olympic Council president and AOF executive member Tom Blue said the federation had already decided to accept Brisbane City Council’s bid, provided it had Federal and State Government support.

Mr Patching said some of Brisbane’s existing facilities were much better than those in Los Angeles.

“Boondall would enhance the whole scene,’’ he said.

Mr Blue said more facilities would be needed but costs would be a secondary consideration because of the enormous spin-offs through tourism.

Students first

By April 1984 Local Government Minister Russ Hinze backed Brisbane’s bid for the 1987 World Student Games as a prelude to staging the 1992 Olympic Games.

Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen also came out in support.

“Brisbane and Queensland are ready for it,’’ he said.

“The coming Expo 88 will prove that, and the Olympics will be a natural progression from that and the highly successful Commonwealth Games.”

Fears and tears

Cracks appear early

In June 1984 Brisbane was already being urged to consider contingency plans – shooting for a second Commonwealth Games.

Ian Brusasco, a prominent sports administrator, said Brisbane could follow the lead of Edinburgh, which held the Commonwealth Games in 1970 and again in 1986.

“If this goal (of the Olympics) is a little beyond us, and the possibilities are not there for them to come to this city, we should again be making noises for the Commonwealth Games,’’ he said.

He also said better use should be made of Brisbane’s sporting facilities; the QEII stadium should be floodlit to attract international sporting events.

‘Devastating effect’

Fears were doubled later in June 1984 when Queensland Senator Michael Macklin claimed the 1992 Olympic Games could have a devastating effect on Brisbane.

“The Games, if held in Brisbane, will be a waste of taxpayers’ and ratepayers’ money. They will also embroil Brisbane in the international political arena and its problems,” he said.

Lord Mayor Roy Harvey dismissed the comments as typical of the negative stance adopted by the Australian Democrats.

“He is talking out of ignorance, lack of knowledge, lack of facts,’’ he said, adding the Olympics would provide immense benefits for the entire nation.

By July, however, even the State Government was having second thoughts.

Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen said a Brisbane City Council feasibility report would require detailed investigation.

“We will need to do our sums carefully on this one,’’ Sir Joh said.

‘Quite slim’ chances

Barcelona appeared the frontrunner from the start.

In August 1984 officials were warned Brisbane faced a long – but worthwhile – battle to stage the Olympic Games.

Sports administrator David Williams said most host cities had to make several bids for the Olympics before succeeding.

“There is consensus in LA that Barcelona in Spain is the frontrunner for the 1992 Olympics,” he said.

“Brisbane’s chances appear quite slim for 1992, but this should not deter us. Los Angeles had to keep trying for about 12 years before it won the nomination.’’

Accommodation concerns

In December 1984 Brisbane was warned that spectators at an Olympic Games in Brisbane in 1992 would have to seek accommodation at Toowoomba, Noosa and the Gold Coast.

Brisbane town clerk Tony Philbrick said accommodation near the city would be taken up by Olympic competitors, officials and media representatives.

“Other people coming here will have to stay out of the city at places like the Gold Coast, Noosa and Toowoomba,’’ he said.

“It is not possible for us in Brisbane to accommodate all these people.’’

Infrastructure issues

Facilities boost

In February 1985 it was revealed Brisbane would gain sporting facilities worth $112 million if it won the right to host the 1992 Olympic Games.

Lord Mayor Roy Harvey said if the bid was successful the Brisbane City Council’s plans for Olympic facilities included a $2.3 million equestrian centre at Murarrie, a $10.5 million annex at the Chandler sports centre and additions totalling $47 million to the Boondall Bicentennial project.

Cr Harvey said the facilities represented Brisbane’s contribution to the $763 million cost of the Games, calculated in 1984 dollars.

The Federal Government would contribute $63 million and the State Government $40 million.

“All costs will be covered,’’ he said.

The $1.8 million cost of bidding for the Olympics was expected to be split three ways between the council and State and Federal Governments.

Hotel plans

In November 1984 work started on the $100 million second stage of Brisbane’s Wintergarden Centre, which will include a Hilton Hotel.

Lord Mayor Roy Harvey said the 340-room Hilton Hotel would help attract conventions and tourists to Brisbane, and also provide accommodation for visitors to Expo 88 and the 1992 Olympic Games.

‘Olympic connection’

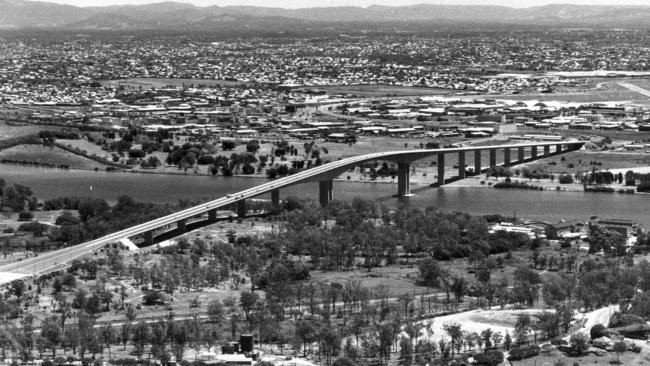

The first stage of the Gateway arterial project, bypassing Brisbane via the Gateway Bridge, was opened in March 1985.

The 49 km route, dubbed the “Olympic connection’’, was expected to greatly assist the city’s bid to host the 1992 Olympic Games.

Stretching from the Bruce Highway at Bald Hills to the South-East Freeway at Springwood, the road would link the major Olympic sport venues.

This was being built by Tomwin Pty Ltd at a cost of $2.7 million.

“This scheme is a vital plus in our bid for the Olympic Games,’’ councillor Russ Hinze said.

Weird and wonderful

Dam good news

In October 1984 it was mooted the Olympic rowing competition could be held on the giant Wivenhoe Dam if Brisbane’s Games bid succeeds.

The Brisbane and Area Water Board offered the Brisbane City Council the “Sheep Station Creek area’’ of the dam as a possible Olympic rowing venue.

The proposed expanse of water runs roughly parallel to the dam wall for almost 5km. Recreation areas are being created at each end, from which spectators could watch the races start and finish.

The council had previously looked at the Southport Broadwater and the Hinze Dam for rowing.

SA aid

If Brisbane’s bid to hold the Olympic Games in 1992 was successful, South Australia’s Hindmarsh Stadium was likely to be one of the major venues for the soccer tournament.

Brisbane in February 1986 was forced to rethink its plans for the soccer program because Lang Park was heavily committed to rugby league.

It was then suggested Brisbane might farm out’ the soccer, the biggest Games crowd-puller, to other Australian cities.

Organisers had originally planned to play the majority of Olympic soccer matches at Lang Park, but the politics of FIFA and a shortage of world-class venues in Brisbane saw plans change.

From russia, with love

The Soviet Union in November 1984 threw its support behind Brisbane, indicating it would send competitors to the 1992 Olympic Games if they are held in Brisbane.

Lord Mayor Roy Harvey said he and Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen had recently held talks with the Russian ambassador to Australia on Brisbane’s Games bid.

“The Russians will be sending delegates to the Brisbane Expo and they will also be sending competitors to our 1992 Games, because Australia was represented at the Moscow Olympics,’’ he said.

Mr Harvey said one reason why the Russians favoured Brisbane as a Games site was that they saw Australia as a peaceful zone.

Seoul assist

The fun and Games could have come early to Brisbane, with the city touted as a possible host for 1988 if trouble in South Korea forced that country to pull out.

Federal Sports Minister John Brown said while a pullout was unlikely, he praised Brisbane in April 1986 and said the city could jump in at short notice if needed.

Winter wonderland

The 1992 Olympics, if Brisbane won them, could be held in winter and not summer, it was suggested in August 1985.

Lord Mayor Sallyanne Atkinson agreed that the Olympics might be held during the designated Brisbane winter months of June-July-August if that is required to convince International Olympic Committee members to award the Games to the city.

“What we’re interested in is holding a sporting event, to have the best Games possible by ensuring that the majority of athletes are competing at the peak of their fitness,’’ she said.

“Given the weather we’ve had this year, for example, we could have held the Games at any time.’’

Brisbane was the only southern hemisphere city among the six candidates for the 1992 Games.

Brisbane’s own ‘Games’

Tokyo and Seoul were touted in November 1989 to stage annual “private enterprise’’ Games in rotation, with the first in Brisbane in October 1991.

The multi-sport Games, the brainchild of Brisbane businessmen Barry Maranta and Barry Paul, was to be funded by private sponsorships and tailored to the demands of television networks in Australia, Japan and South Korea.

“We will be attempting to do with a Games formula what Kerry Packer did with cricket,’’ Maranta said.

Like Brisbane, whose 1982 Commonwealth Games facilities remained under-utilised, Tokyo and Seoul were desperate to stage regular events to make use of the stadiums built for the 1964 and 1988 Olympics.

Controversies and confusion

PR plan

It was revealed in May 1985 that Brisbane City Council paid a London public relations firm $26,000 as part of the city’s bid for the 1992 Olympic Games.

The money had been paid by the previous Labor council to Shandwick PR, a London firm employed in a “sounding out and lobbying exercise’’, the Lord Mayor Sallyanne Atkinson said, confirming the council also had paid $30,000 to a Sydney advertising company, MDA.

Village sale

Heads turned in May 1985 when a Brisbane City Council senior officer claimed if Brisbane won the 1992 Games homes at the Olympic Village will be sold to the public before the event.

The Olympic Village, planned to be built near the Boondall sports complex, was due to be

part of a bayside suburb to be developed on 900ha of council land stretching from Cabbage Tree Creek to Nudgee Beach.

Under council planning, the Olympic Village, to be built on a site of about 150ha, had to be able to house 12,000 athletes and officials for three to four weeks during the Games in August-September 1992.

It was claimed that houses and units would go on sale shortly before the Games, and buyers would be able to move into them almost immediately after the Games.

Flood worries

Brisbane City Council’s plan to build a new suburb and Olympic Village at Boondall was frightening, a Labor councillor said in June 1985.

Ken Leese, of Deagon ward, where the new suburb was due to be built, said the project could have disastrous effects on the local area.

He said the plan to build a marina and island off Boondall could cause serious flooding problems for the suburb of Deagon.

“God help Deagon,’’ he said.

Mr Leese said the council was proceeding with “indecent haste’’ to get the project started in order to boost Brisbane’s chances of securing the 1992 Olympic Games.

Mr Leese said the entire development had been “thrown in the lap of the developer’’.

Lord Mayor’s ‘mishandling’

A major row erupted in July 1985 over Lord Mayor Sallyanne Atkinson’s handling of Brisbane’s bid.

Brisbane City Council Opposition Leader Peter Walsh said Ms Atkinson was trying to hoodwink ratepayers into believing the 1992 Olympic Games were not a council responsibility.

The Lord Mayor said that an Olympic Projects Office would be set up to take organisation of the games bid out of the mainstream of council activities.

Mr Walsh said it had to be remembered that the council was making the bid for the games and their cost had to be guaranteed by the city and therefore the ratepayers.

“There is no way that the games can be removed from the control of the council,’’ he said.

“Mr Atkinson’s statement that the games and the games bid were not a council activity is absolutely ridiculous.’’

Rebels without a cause

In May 1986 it was revealed Brisbane’s biggest threat to hosting the Games came from events in apartied South Africa.

South African Non-racial Olympic Committee secretary Sam Ramsamy said Brisbane had the facilities to stage the Games but the actions of sporting “rebels’’ could sway the floating vote of African and Asian nations.

He said he would recommend Brisbane to African delegates of the International Olympic Committee.

“Brisbane’s facilities are superb,’’ Mr Ramsamy said.

“Not all the other places I’ve been to can provide everything within the boundaries of one city.

“But if sportsmen and women want the Games in Brisbane, they ought not to have contact with South Africa.’’

Mr Ramsamy said a proposed visit to South Africa by Queensland swimmers could tarnish the city’s chances of securing the Games.

Public opinion

Residents unite

A survey on the attitudes of Brisbane residents in April 1986 helped drive the steps towards a Games bid.

It was revealed 60 per cent favoured Brisbane hosting the 1992 Olympic Games, with 22 per cent saying they were not concerned either way.

While only 17 per cent were against it, mainly because of concern over possible future debt and expense.

City gets on board

Brisbane broadcasters in August 1986 got behind the city’s bid for the 1992 Olympic Games.

Stations Stereo 10, FM104, 4KQ and 4BK joined forces and pledged thousands of dollars’ worth of prime time to promote Brisbane during the weeks before the host city was announced on October 17.

Television station Channel 0 also threw its cap into the arena with airtime worth $30,000 for the Games bid.

Community affairs representative for the Olympic Project Office, Macey Kavalee, said managers from the four radio stations met a week earlier and agreed to broadcast promotional spots featuring the new rock song for the bid, Brisbane is Ready.

After the doomed bid

Development no-go

Brisbane City Council in October 1986 scrapped plans for more than $80 million worth of sporting facilities in the wake of the failed 1992 Olympic Games bid.

Deputy Mayor Denver Beanland said most of the planned facilities had been “purely to do with the Olympics’’ and Brisbane had no use for them after Barcelona was chosen.

Projects which were dropped include stage two of the Boondall Sports Centre, boatsheds and rowing facilities at Lake Kurwongbah, an equestrian centre at Cannon Hill and a multiple sports annex at Chandler.

The council was to have spent $12.9 million on the Boondall Aquatic Centre (diving), $2.7 million on Lake Kurwongbah (canoeing, rowing) and $23.5 million on the Chandler annex (judo, table tennis, fencing and wrestling).

Mr Beanland said foundations had been laid at Boondall for two 6000-seat sports halls ($35million), but these would not proceed.

The council also was no longer interested in a joint project with the Australian Equestrian Foundation to build a $4.9 million centre on the banks of Bulimba Creek.

Pushing the envelope

Not one to give up easily, Brisbane in July 1987 considered a referendum to decide if it should bid for the 1996 Olympic Games.

But Brisbane Lord Mayor Sallyanne Atkinson said any decision on an Olympic bid would not be made until 1990.

Her comments followed statements from Judy Patching, the Oceania Olympic Committee chief, who said Brisbane would be looked on favourably in a 1996 bid.

Alderman Atkinson wanted to ensure any decision was not made in secret.

“There would be involvement by the people of the city,” she said.

“That could take the form of a referendum or getting in touch with the residents with a quiz to go in their rate notices.”

Money management

Some of the money left from Brisbane’s unsuccessful bid for the 1992 Olympic Games was in December 1987 reallocated to fund the Brisbane Olympic Award, which provided an athlete with $5000 to help devote their final year to training for the summer Olympics.

‘We lost our momentum’

Brisbane would have been assured of being Australia’s nomination for the 1996 Olympics if it had declared its candidacy after its unsuccessful 1992 bid.

AOF president Kevan Gosper said in November 1988 that had Brisbane declared its ongoing candidacy for 1996 straight after finishing third in Lausanne, it is possible none of the other Australian cities would have indicated interest.

Lord Mayor Sallyanne Atkinson said she had not committed Brisbane to another bid until she had assessed its mood after the start of Expo.

“In any case, it was not a decision for me alone. It had to be a decision of the City Council.’’

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Worthless’: Sports clubs’ sobering child safety warning

Child safety experts have delivered a confronting verdict on background checks and reporting systems after Sport Integrity Australia complaints data revealed junior sport's hidden dangers.

Boats, bikinis, beers… and other secrets of musclebound mayor’s success

From Minister for Muscles all the way to City Hall, Nick Dametto reflects on the extraordinary ingredients that have driven his colourful career. WELCOME TO HIGH STEAKS