Purple Haze to popping pills: The evolution of party drugs

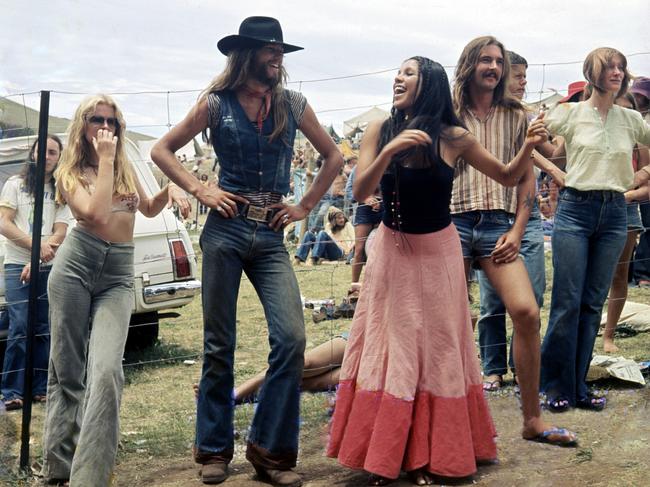

Peace, love and LSD. When music festivals began taking shape in the 1970s, Australia was a different place — hair was long, times were radical. Fast forward 50 years and the festival landscape couldn’t be more different. Nor could the drugs.

The Ripple Effect

Don't miss out on the headlines from The Ripple Effect. Followed categories will be added to My News.

‘The brown acid circulating around us isn’t any good … it’s your own trip so be my guest, but please be advised there’s a warning on that one, okay?”

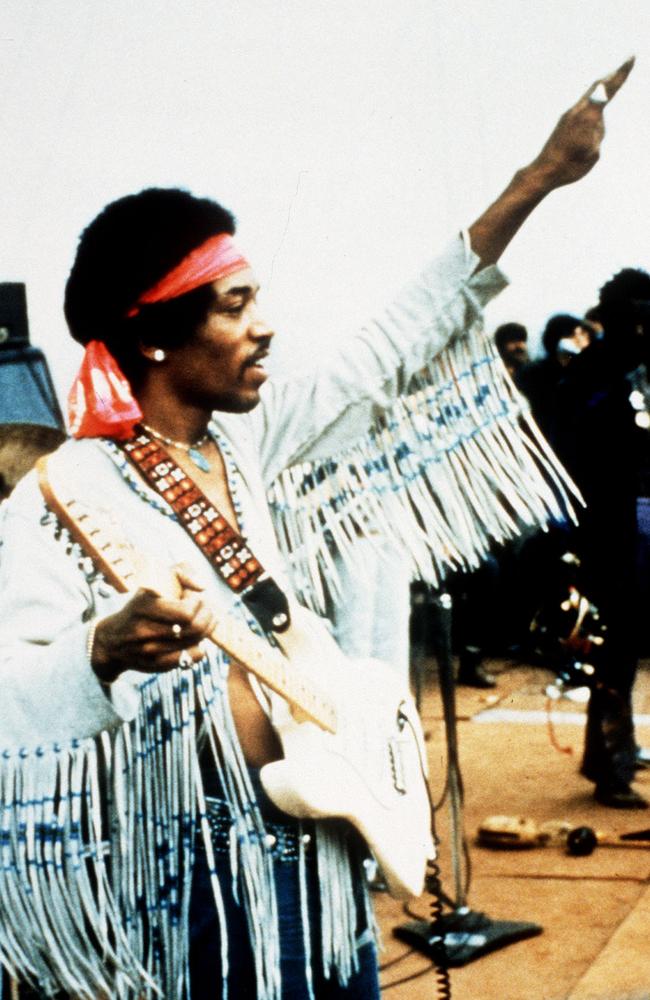

That laissez-faire drug warning remains a defining moment of Woodstock, the 1969 event that set the benchmark for all music festivals to come.

Almost half a million mud-caked young people tripped on acid, dropped mushrooms and smoked weed, fixated on a stage where the greatest rock line up had assembled — Hendrix, Joplin, Creedence, Santana. There had never been anything like it.

Six months later, Australia got its own large music festival — Pilgrimage of Pop — on the NSW Central Coast and for the next decade, counterculture Boomers got high at a myriad of events where drugs traded freely and policing was done with a light touch.

Fast forward 50 years and the music festival landscape couldn’t be more different.

Casual drug warnings are gone, replaced by drug dogs and intense security. LSD has been replaced by MDMA caps of unknown purity and alarmingly varied contaminants.

And summer festival drug-deaths are now a regular occurrence.

How did we get here?

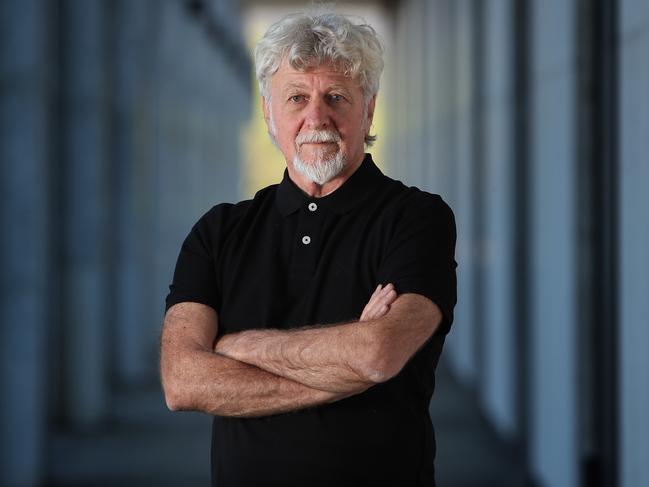

For Robbie Swan, today’s festival scene is a long way from the 1970s when events like the Aquarius Festival in Nimbin garnered plenty of media attention but little police interference.

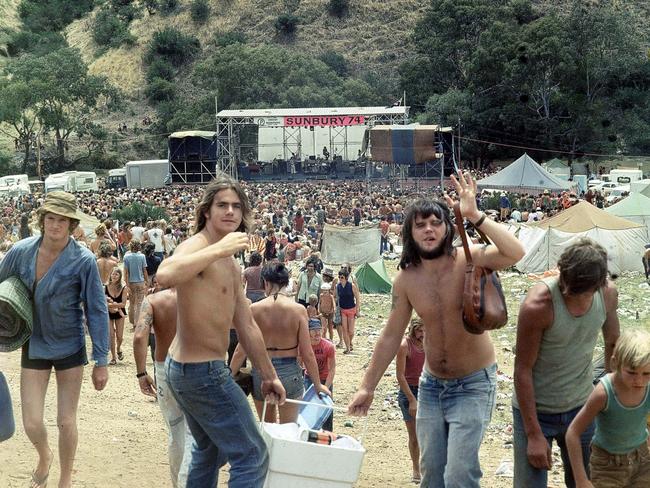

Aquarius wasn’t as big as other events of the decade like Pilgrimage of Pop in 1970 or 1972’s Sunbury in Victoria, dubbed Australia’s answer to Woodstock. But it set the tone for many future events — the lifestyle, ideology and vision of folk festivals.

More than 7000 young people descended on the tiny NSW dairy town in May 1973 for the ten-day event and while the sex, drugs and nudity preoccupied media, the pot and LSD being consumed was of little interest to police, said Swan.

“Back in the 1970s when music festivals first started, psychedelics weren’t considered that bad,” Swan told The Ripple Effect.

“The moral panic was more about the fact that people weren’t having a shower.”

The ‘70s in Australia were a good time to be a young person.

Hair was long, times were radical and the Australian counterculture was reaching its peak.

The decade’s first Liberal Prime Minister John Gorton supported decriminalising marijuana and LSD had been available in large quantities for years.

But recreational drug use wasn’t a big concern among “tree-hugging soap-dodging” hippies.

“The coppers just never came into the festivals, they just weren’t interested,” Swan, now 68, said. “I remember at the 1971 Aquarius (festival in Canberra) … Ray Sweeney and Charlie Kent, the two drug squad guys, went there but they were just doing reconnaissance.

“They were after information about heroin coming into Canberra.

“People were smoking dope all around them and they didn’t give a rat’s arse.”

THE JOURNEY

For Swan and his peers, drug taking at music festivals then was about self-discovery, experimentation and finding a sense of unity with others.

“I hesitate to say it was a spiritual experience but it kind of was,” he said.

“We were looking for an existential experience where you could reach a state of nirvana, it wasn’t always about having a good time but about testing the limits of your intellect, your ability to be present among pretty strange circumstances.”

Not that people didn’t have bad trips, get sick or get arrested but there were no sniffer dogs outside events. And compared to today’s illicit drug trade, the wheeling and dealing of pot and psychedelics seemed almost innocent.

“It wasn’t organised crime … they were just hippies who dealt drugs,” Swan added.

“People were making their own psychedelics here, there was no reason to pollute it.”

Swan, who co-founded the Reason Party with partner Fiona Patten, is a long-time advocate for the decriminalisation of cannabis and “sensible” drug policy.

He believes in 50 years of festivals and drug use, prohibition has ignored one uncomfortable reality. People take drugs because they enjoy it, and for some, the experience is “very meaningful”.

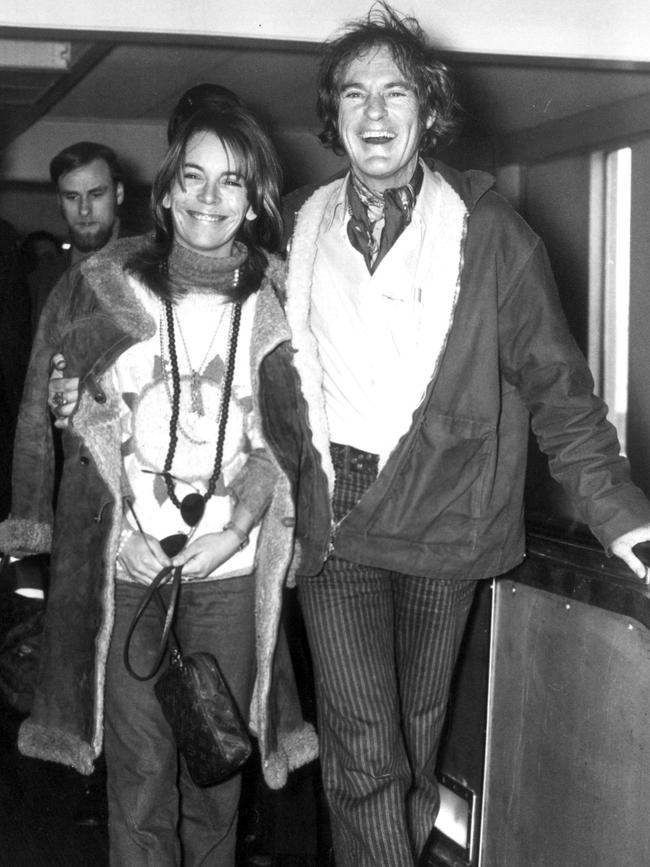

“I remember the first time I took MDMA I was working for Richard Neville,” Swan said.

“We were up at his place in Blackheath one night (in 1986) and he said, ‘Timothy Leary’s just sent me through some samples of this new drug, would you all like to try it?

“We all took it that night up there and just had the most wonderful time. I think it was only about six months after that MDMA was criminalised and put into the same basket as heroin.

“I remember thinking, they could have looked at that and realised its therapeutic qualities.

“But they just simply ban it and as soon as they do, they hand it over to the black market.”

RISE OF ECSTACY

Swan was probably one of the earlier consumers of MDMA because it wasn’t common at the large-scale rock festivals of the decade such as Tanalorn in ‘81 or Narara in ‘83 and ‘84.

Narara on the Central Coast was massive. Tens of thousands poured in to see INXS, Cold Chisel, the Divinyls and Talking Heads and by many accounts, it was a free-for-all.

Festivalgoers bought five-litre wine bags at the bar for $20, dropped superman acid trips and watched bikies “mull up” for breakfast.

“I remember some bloke wandering around with a garbage bag full of weed making some handy beer dollars,” wrote one festival goer in an online forum about the ‘83 and ‘84 events.

“A mate and I were packing a bong when we looked up and saw these three coppers walking past looking at us. One of them just winked at me and they continued on their way. I bet that wouldn’t happen nowadays,” wrote another.

While police seemed to turn a blind-eye to what went on inside festival gates, outside alarm bells would start to ring by the decade’s end.

By 1989, ecstasy had flooded into Australia, St Vincent’s Hospital was at one stage fielding five ecstasy-related cases a day. NSW Drug Offensive director Michael MacEvoy told a parliamentary inquiry ecstasy use was booming and had caught authorities off guard.

The drug’s communal euphoria had seen it thrive at warehouse parties, underground raves and in the gay and lesbian party scene, before going mainstream in the 1990s.

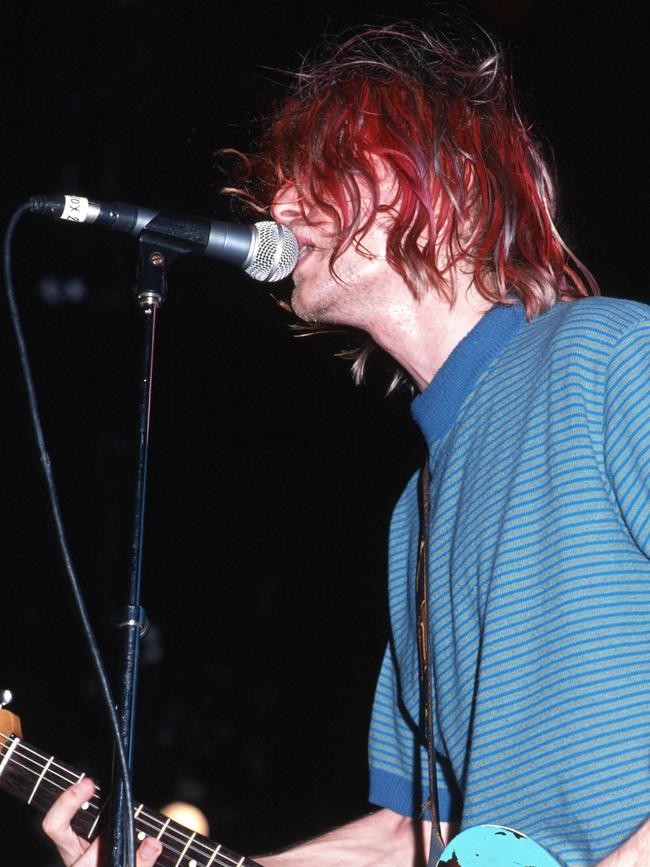

By the time alternative music exploded and the Big day Out kicked off in ‘92, it was among the myriad of drugs on the menu.

A SMORGASBORD

Sitting in a room of 40-something gen Xers who spent their youth at 90s festivals such as BDO, Livid and Homebake, the group agreed drugs then were a mixed bag.

Weed, speed, ecstasy and microdots (LSD) were all available and easily smuggled into events although double dropping ecstasy pills was not the norm. They were pretty strong.

“Most people took half and waited to see how strong they were,” said one, adding a single pill or microdot was usually enough. “They’d last a good eight hours.”

There were bag checks but no one recalled drug dogs and while “everyone was wasted” and venues were pass-out packed, no deaths occurred.

At least not until 2001, when Jessica Michalik died after being crushed in a mosh pit during a set by Limp Bizkit at the Big Day Out.

That tragedy shook organisers and took the shine off the event, which by then was no longer the domain of alternative subcultures.

But it didn’t spell the end of festivals … by the 2000s, they’d exploded.

Nick Wallis, Australian Psychedelic Society President, said people started using a much wider variety of drugs in the ‘90s and into the ‘00s as festivals popped up around the country.

By then, events such as Rainbow Serpent, which started in 1997, had joined the mix.

A four-day open-air electronic music, art, and lifestyle festival in Lexton, Victoria, Rainbow Serpent was known for its psychedelic trance and chill-out music and grew to attract about 12,000 a year. For Wallis, it was one of the first he experienced

“I was a bit reluctant to go to festivals because the ones I heard about when I was in my early 20s all sounded like they’d be the nightclub experience but even more intense,” said the 33-year-old, from Melbourne.

Eventually, he was convinced to head to Rainbow Serpent with a friend, and around the same time, attended his first Confest and Entheogenesis Australis conference on psychoactive plants.

“They were the first festivals that I actually felt at ‘home’. It was never just about the music for me. It was always about the broader community, the wider engagement, the conversations beyond the party, the pursuit of knowledge about a whole range of topics that I found lacking in the mainstream drunken scenes.”

His wasn’t a hedonistic get-wasted approach at those events. He drank a few beers, smoked the odd joint and occasionally, took magic mushrooms, but never to extreme.

“Each of those festivals but particularly EGA and Confest have a focus on community building through workshops, talks etc. and generally it’s good to be mostly sober to enjoy the content,” he said.

There was also an in-built harm reduction approach among festival goers, he said.

“I came from a relatively cautious approach to psychedelics and was always with close friends at early festivals,” he added.

“We took care of each other and didn’t push ourselves too hard. Again, this was my personal experience at early festivals that I went to. I began to get involved with these communities as I started to attend again and again.”

TIMES HAVE CHANGED

Wary of sounding like a “jaded old person”, Wallis still attends some festivals but says the culture has changed as events became bigger and more commercial.

“The people who were for lack of a better word, guiding the culture … just got outpaced by the sheer number of people coming into this scene, which essentially saw a mainstreaming of the doof culture and a mainstreaming of that drug culture,” he said.

“And with the Australian attitude to alcohol, of bingeing, where it’s really funny if someone throws up and has too much, just push, push, push against things, I think we’ve seen that go into drug culture.

“I’ve seen that a bit, like when someone’s had maybe too much of a drug, perhaps ketamine and they’re passing out and their friends decide that the solution to that is to try and shovel speed into their nose.

“I don’t think it’s hugely prolific, generally their friends are pretty intoxicated too, but this is when things really go awry.”

An executive producer of 3CR's Enpsychedelia, which covers drug policy issues, he says there’s more information about drugs than there used to be. But the continued belief prohibition can stem the tide of new drugs or stop people from wanting a drug has failed.

“I think there’s a big role that prohibition plays in driving demand and trends for drugs,” he added. “I know (anecdotally) that the intense focus on methamphetamine has actually driven demand for the drug in some cases.”

THE RISE OF MDMA

In a year when festival drug-deaths have dominated headlines, drug bingeing and purity have never been more scrutinised, especially in the case of MDMA.

For Jackson, 26, who started going to all-night warehouse parties almost 10 years ago before graduating to festivals, both played a role in how he and his peers have used drugs.

When the Sydney man began taking ecstasy as a 17-year-old, MDMA caps were a rarity.

“There were a lot more pills then which were much better than caps because I guess they were European, they were stronger, they were more pure,” he said.

“Getting your hands on the good ones was amazing. It was a different sort of feeling to your MDMA caps, a lot more euphoric and chargey.”

But about five years ago, ecstasy pills disappeared and MDMA caps took over.

“The big difference I started to notice was they just weren’t as good,” he said.

“You would be a lot more smashed from it. You’d be a lot more munted, I can’t f**king stand up, eyes rolling into the back of your head.

“Whatever was put in them that was garbage … the quality just became a lot worse.

“I think then people started to have a bit more, because of that.”

Two, three four caps soon became the norm at an event, although some people dropped six, eight, even more.

Jackson’s never tested a pill or cap and doesn’t think it’s that common among festivalgoers.

But findings overseas have identified more than 500 adulterants in drugs sold as MDMA including dangerous compounds like PMA. They are not all weaker.

UK pill testing at festivals has identified MDMA doses of up to 250-300mg per cap, which is extremely high. Equivalent tests in the ‘90s revealed the average pills were 50-80mg.

It’s that mix of high-strength caps and inexperienced users that’s so toxic at festivals, especially when users are front-loading their drugs before getting through the gates.

These days, Jackson doesn’t do drugs or festivals. In the end, the scene became too much, the drugs stopped working and he was taking them to mask deeper issues in his personal life.

It wasn’t the debate about drug deaths that changed his path and he doubts it will stop others taking MDMA at festivals.

“There needs to be more education” he added.

“Know your limits, know your threshold, look after your mates.”

Originally published as Purple Haze to popping pills: The evolution of party drugs