Wolston Park Hospital left to rot as former ’patients’ continue fight for justice

“THEY would strip you down, put a straitjacket on you, stick drugs in you… they experimented on us.” Real-life stories from inside Brisbane’s notorious mental hospital.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

NOTHING can quite prepare you for it, your first sight of this fading house of horrors, this pale wood and rusted tin wound of a building that sits on a rise overlooking a beautiful stretch of the Brisbane River at Wacol, 18km southwest of the Brisbane CBD.

One moment you’re driving down the pleasant, tree-lined Boyce Rd, passing the manicured greens and neatly mowed fairways of the Wolston Park Golf Club that hugs a sharp bend in the river. Then you hit the T-junction with Ellerton Rd, and there it is up the hill – the former Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum, later named the Goodna Asylum for the Insane, then the Brisbane Mental Hospital, then the Brisbane Special Hospital, and then the Wolston Park Hospital Complex – this ramshackle testimony to unimaginable suffering and abuse.

In Sydney they had Callan Park. Melbourne had the Kew Lunatic Asylum in the inner city. For Brisbanites, just the mention of the words “Goodna” or “Wolston Park” meant the mental asylum, that place tucked into the outer folds of the city that was best not talked about. (It is currently called The Park Centre for Mental Health.)

Woogaroo (believed to be an indigenous word meaning “to step over a person lying down”, according to Griffith University historian Professor Mark Finnane) opened its doors just after Christmas in 1864, and the original asylum still sits there, battered by the elements.

And like a tricky historical stain, its heritage listing means it cannot be demolished, but its total disrepair would suggest it would be too prohibitively expensive to restore.

So there it remains today, surrounded by fencing and barbed wire, not quite of this world. Someone has spray-painted on one of its outer walls: WELCOME TO HELL.

After a century and a half, it rests at the edge of a large working Queensland Government mental health precinct, a veritable village of wards and clinics and practices and treatments that have left the old days behind.

But it’s the old asylum and its ghosts you cannot look away from. And the ghost that nags you the most is that of Isabella Lewers.

In late 1866 – less than two years after the asylum opened – Lewers, 22, by all accounts a “very quiet, good girl” but “weak-minded”, had “improper intimacy” in the grounds of the asylum with chief warder W. J. Haddon. The incident was referred to in parliament as “the grossest case that had ever occurred in an asylum”, and that if asylum staff were not more vigilant, Woogaroo would become “a foul stain upon humanity”.

So began, with Isabella Lewers, generational abuse at the Wacol site that would stretch over a century, a cycle of sexual assault and torture that would produce many hundreds, if not thousands, of victims. This foul stain we can’t get rid of.

There is an eerie quiet here. Except for large colonies of white cockatoos, flocks of which zip and frolic between the ancient pine trees and eucalypts, above the golf course and the hospital grounds, swirling and whirling like large, mad, white bedsheets caught in wild gusts of wind. And their sudden bursts of communal shrieking scratches at the back of your mind.

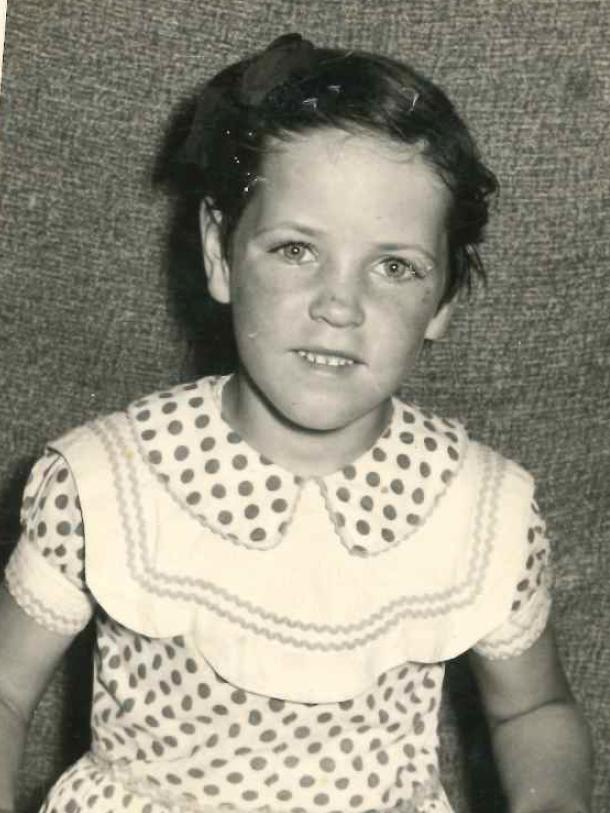

Only 11km or so down the Brisbane River from the old Wolston Park asylum, in the suburb of Jindalee, Barbara Smith, 72, is making a cup of instant coffee. On this day she is wearing a battered Manly Sea Eagles rugby league cap, khaki shorts and a Pink Floyd T-shirt.

Barbara is full of life, a powerhouse with a ribald sense of humour and who uses language, on occasion, that would make a veteran sailor blush. She is an avid reader, a huge consumer of current affairs, loves dogs and, when required, is as tough as boots.

Barbara is also connected to the ghost of Isabelle Lewers. As a child, she was an inmate of Wolston Park. And like Isabelle, she too suffered almost indescribable abuse at the hands of warders and other patients.

She sits on her lounge chair and places the coffee cup on a coaster on the coffee table and remembers when she was institutionalised in Wolston Park in the late 1950s and into the 1960s, when she was only 15. She was deemed a recalcitrant, a “JD” or juvenile delinquent, at a time when then corrupt Queensland police commissioner, Frank Bischof, had whipped up public hysteria about dangerous “bodgies and widgies” taking over the streets of Brisbane.

This resulted in a special government committee being appointed to look into “youth problems”. Its final report, tabled in Queensland parliament in 1959, read in part: “One of the worst features of modern youthful misbehaviour lies in the participation by young girls. This seems to highlight the main difference between today’s problem and that of two decades ago.

“Presence of young girls produces several additional bad reactions. As well as vandalism and wilful destruction it introduces sex delinquency with its danger to the younger teenage girls.”

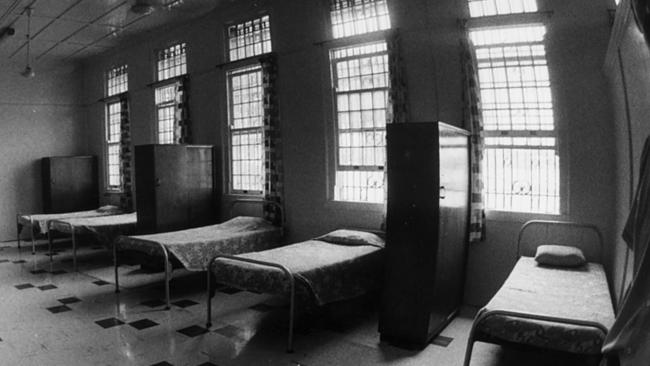

In this appalling context, Barbara Smith, who was neither a widgie nor a delinquent, was committed to Wolston Park. “I was in there for three years,” she says. “While in there I lived in a straitjacket. They also injected you with (the drug) paraldehyde (a central nervous system depressant routinely used in mental hospitals around the world up to the 1960s). If you had to have paraldehyde they’d get the male warders over to hold you down while they stuck the paraldehyde in your leg, and when you woke up you had semen all over you. (She was also injected with the antipsychotic medication Largactil, and was given three doses of Valium per day.) “As for the beatings … from the patients … and from the nurses … the nurses would tell the patients … they would stir things up. I’d sit at a table and there’d be one who jumped across the table and battered me. We slept in single rooms, the young girls, there was about five of us in there.

“They would strip you down, put a straitjacket on you, stick paraldehyde in your leg … you got so many different drugs … they experimented on us …

“I have got chronic renal disease, I had a heart attack and a stroke in 1985 and I’ve just had two heart attacks in the last year … I suffer something shocking with a lot of health problems.

“They’d take you over for shock treatment. They didn’t even sedate us. They’d strap us down and put the thing in your mouth and put the electrodes on your head. We were little girls. Where was it right?”

Barbara’s path to hell could’ve happened to anybody. An unexpected crack appeared in the foundations of her childhood, and she simply fell through it. Born in Maryborough, she was barely a toddler when her mother, Rona, took up with another man while her husband, William, was serving in Japan near the end of World War II. Rona went to New Zealand to be with her new partner, leaving her children behind in Brisbane.

Barbara and her brother, Robert, and sisters Margaret and Rona, were cared for briefly by a relative before it became “all too much” and the sisters were sent across to the Queen Alexandra Home for Children in Coorparoo in the city’s inner east. Robert was adopted out.

Barbara was almost two years old. It was the beginning of her institutionalised life that would ultimately lead her to Wolston Park. At each foster home and orphanage she progressively found herself in, she was sexually assaulted and abused.

The plucky and “uncontrollable” Barbara – she had made several escape attempts from institutions – was then placed in the notorious psychiatric unit Lowson House, within the grounds of the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital at inner-north Herston.

“They locked me up for three months in solitary confinement and fed me drugs,” she says. “They made me out to be this sort of monster.” After that, she was “carted off” to Wolston Park.

“Goodna was for the criminally insane,” Barbara adds. “They put me in the admission ward for about six months, then they decided to put me in one of the back wards. I ran away. I found a screwdriver on the ground and I unscrewed the screws on one of the windows.

“I got a job. I met somebody. But I didn’t know he was going with another girl and she rang the police and put me in. They took me back to Goodna and put me in Ward 8 with the criminally insane. Why would you do that to a 15-year-old girl?”

She says the sexual abuse was rampant. “There were no doors on the toilets or bathrooms,” she remembers. “Male warders would stand there and remark about our bodies. They’d come and maul us and molest us all the time. I can’t stress to you enough the horrors of that place. It was a bloody disgrace.

“Children died out there. Babies were aborted. There’s that many graves out there of children who died. But the cruelty, the sheer cruelty, inflicted on innocent children … I can’t emphasise enough the cruelty.”

Barbara Smith was released from Wolston Park in the early 1960s, when she was 18. But her experiences there stigmatised her, deprived her of a fulfilling career, and ruined her health. “I’ve had a turd of a life,” she says.

An hour south down the highway, at Nerang, On the Gold Coast, is Sandra Finn, in her 60s. She too is one of the last surviving “Wolston Girls”, as they call themselves. She also fell into an unstable life when, as a small child in Sydney, her father died of a brain aneurysm and her mother abandoned her and her siblings.

Sandra ended up with her sister on the Gold Coast. She ran away from home a lot and was ultimately categorised as a “neglected child”, and in the late 1950s was installed in Tufnell Home, an orphanage for “poor children” in the Brisbane suburb of Nundah, 8km north of the CBD.

She escaped soon after, was captured and returned to the home, then was sent to a variety of institutions, from the Good Shepherd Home for Girls in Mitchelton, in northwest Brisbane, to Karrala House – the female ward of the Ipswich Mental Hospital. Its primary patients were “delinquent girls”.

“I’ll never forget getting out of that cop car (when she was taken to Karrala House),” says Sandra. “I had my hands behind my back and I remember looking at the cop and thinking, if I could get his gun I’d shoot myself. I was about 13 or 14. That’s when I did 34 days’ solitary. Pitch blackness. Absolutely nothing. I was as mad as hell when I came out. I gave them a hard time … so they sent me off to Wolston Park.”

To protect her from male warders, she says a nightshift nurse who took pity on her intentionally drugged her until her return shift the following evening.

“When she used to go off work at 6am, she used to give me a dose of haloperidol (another antipsychotic drug) and that knocked me out until she started her shift again the next day,” Sandra remembers. “She said, ‘We have to drug you up and lock you up to keep you safe’.”

The nurse’s valiant efforts didn’t save Sandra from predators. “It was unknown sexual abuse. It was worse than sexual abuse. You’d wake up and know that someone had been at you. You knew but you didn’t know what was done, who was there, what happened. That was so scary.”

Sandra was in Wolston Park for just over a year. “I did wake up once with a guy on top of me,” she says. “They were aborting babies, they were sterilising girls. You never got fed. You never got water. You were in that room so much. Our hair was falling out. We had green teeth. I knew that I would die there. I ran. They were going to kill me.”

Sandra managed to successfully escape in 1967, and fled interstate where she tried to start a new life. She didn’t return to Queensland for almost 20 years, fearing she might still be charged for absconding as a ward of the state.

Talking to Sue Treweek, 51, who lives with her children in Marsden, a suburb of Logan City, 27km south of Brisbane, you’re hard pressed to be able to find any signs of the life of torture and abuse she suffered as a young woman and as a next-generation “Wolston Girl”.

She’s intelligent, softly spoken, and measured in her responses. Given she survived her traumatic childhood and teenage years, she shares the resilience of Barbara Smith and Sandra Finn. Born in Mackay in 1965, Sue was in and out of foster homes and orphanages in Melbourne and Brisbane from the age of two, about the time her mother divorced from her father.

“Mum. She used to drink and she’d always meet these abusive men and put us at risk,” Sue says. “I couldn’t take it any more, the abuse at home. I was put into Warilda Children’s Home (at Wooloowin in Brisbane’s inner north). They had isolation cells there, and punishment was to be taken upstairs in the isolation cells.

“I wasn’t very good at it. I couldn’t handle it. One of my stepfathers used to put me into the bread cupboard. I had to stay in the bread cupboard until he got back from work.”

At 12 she was committed to Lowson House for a psychiatric assessment for the first time. A doctor ordered her immediate release. She shouldn’t have been in there. She went to another home and was returned to Lowson House.

She was injected with haloperidol, just like Sandra had been in the 1960s. “I had such a severe reaction that they had to call the crash team … it almost killed me,” Sue says. “My body would distort and twist, my jaw locked and my eyes rolled back … it was really horrific. And extremely painful.”

In the end, given her extended stints at Lowson House, no foster home or orphanage would take her. She had been in a psychiatric institution. She was sent to Wolston Park. It was October 1980.

“I remember that day as clearly as if it was yesterday,” Sue says. “I was transported out there by ambulance. There were some other patients in Lowson House who had told me about Wolston Park. They were terrified; they put the fear of God into me.

“I actually tried to cut my wrists before they transferred me. But I wasn’t very good at it. And my throat. With a piece of glass in the isolation cell.”

Sue, at 15, was placed in Osler House, the women’s high-security ward. She was still supposedly under the care and protection of the state. Within half an hour of being there, she was attacked by a fellow patient. “My odyssey began in there,” Sue recalls.

During her many years locked up at Wolston Park she witnessed disabled children being bashed and sexually abused by other patients and warders. At 15 she was regularly given ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). She was eventually transferred out of Osler House and into a “semi-locked” ward, which allowed her time to stroll the grounds of the mental institution. On a walk one day she was raped by a Wolston Park gardener and fell pregnant.

“They gave me soap and water enemas through my pregnancy … a steel bucket, a garden hose, and hot, hot soapy water … and they’d pump about five litres of soapy water through my bowels,” she says.

Sue was taken to the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital and gave birth to Will. The boy was a healthy 2.83kg.

“I was begging them. ‘Please let me see my baby’,” she says. “I got to hold him and our eyes met and it was like bonding. We instantly bonded. I could never get over it, when they told me I wasn’t allowed to see him again. I held him for only minutes. Only a few minutes, yeah. Four days later they sent me back to Wolston Park. I was put in an isolation cell, naked. They told me to get over it.”

She would remain at the institution for another four years before she made a successful escape with the help of a sympathetic male warder. Sue would not see her son until 2007, when he was 23. She learnt he had been looking for her. “He was told there was no record of me. He was told I was either dead or I was hiding from him. He didn’t know I’d been looking for him for a long time.”

Sue lost almost a decade of her life to Wolston Park. And like the other “Wolston Girls”, it continues to haunt her.

“I’ve never been able to sleep in a bedroom,” she says matter-of-factly. “I’ll sleep in the lounge room, the dining room. The house I’m in at the moment has an entertainment room, and I’ve got a big double door so I can see outside. Otherwise I wake up in the horrors.

“Nightmares. The worst part is I hear the screams of other people … the disabled children … I couldn’t stop what happened to them … the children who never got out of there.”

For some of the surviving “Wolston Girls”, like Sandra Finn, their fight for an apology from the Queensland Government, and ultimately financial redress, began in the late 1990s. Sue Treweek has been lobbying for two decades. Barbara Smith came on board 10 years ago.

But the institutionalisation of children in adult mental asylums in Queensland has been public knowledge for decades. In October 1968, Brisbane Sunday Truth reporter Ken Blanch exposed the case of “Jane Doe”, a 12-year-old girl who was held for 88 days in solitary confinement in Karrala Home for Girls at Ipswich.

Twenty years later, Blanch, working for The Sunday Mail, exposed abuses at Wolston Park in the 1960s and ’70s. The accounts of former child inmates confirmed the accounts of the “Wolston Girls”.

Blanch also interviewed a nurse who alleged that children had been murdered at the institution and the deaths covered up.

“The kids went through hell,” the nurse told Blanch. “It was as bad as any wartime prisoner-of-war camp.”

Canberra-based academic and writer Dr Adele Chenowyth, who is attached to the Centre for Heritage and Museum Studies in the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University, and who has led the push to have the Wolston victims’ stories heard and recognised, and for official redress to be granted, has written an as-yet unpublished book on the subject called Goodna Girls.

As Chenowyth writes in her opening paragraph: “Children were incarcerated in Queensland’s oldest and largest mental health facility, colloquially known as ‘Goodna’. The files that I have read of some of these child inmates include reports by mental health professionals stating that they were not insane. These children either committed no crimes at all, or had only committed minor misdemeanours but they were locked up with criminally insane adults.

“It happened. No denials, no platitudes, no explanations, no victim blame, no accusations of conspiracy theory will change this history.”

Chenowyth says giving the women a voice is important, but there needs to be more after so many decades.

“Let’s be clear. These women want redress, they want financial compensation for the way their lives have panned out as a result of them being incarcerated in Wolston Park,” she says. “They have health issues which are a direct result of the abuse at Wolston Park. Their children have suffered. There needs to be intergenerational awareness of the consequences of this policy. There needs to be some tangible and quantifiable and meaningful response.”

History shows that the “Wolston Girls” have hit roadblocks at every turn over the decades. As Dr Chenowyth writes: “In 1997, a group of Goodna survivors sought legal support and one test case was put forward in the Supreme Court of Brisbane against the State of Queensland.

“In its defence, the State successfully pleaded that the action was barred by the Limitations of Action Act 1974. This Act states that legal actions for personal injury must be commenced within three years from the date of the injury. Victims of child sexual abuse are usually incapable of initiating civil action within this time frame.

“The Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions, known as the Forde Inquiry (1998), excluded Goodna/Wolston Park from its terms of reference. This meant that former child inmates of Goodna were not eligible for ex-gratia payments as part of the Queensland Government’s Redress Scheme (2007-2010) for victims of institutionalised abuse.”

In 2003, the Federal Government commenced an investigation into children sent to adult institutions such as Wolston Park. It ultimately produced the report, Forgotten Australians: A report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children.

The report was the final part of a trilogy of investigations, the others being Lost Innocents, on child migration, and Bringing Them Home, on indigenous children. The Forgotten Australians report looked at the thousands of non-indigenous Australian-born children who suffered under institutional care.

In November 2009, then-prime minister Kevin Rudd issued a National Apology to the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants who suffered neglect and abuse in out-of-home care.

Currently, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has declined to open a “case study” investigation into Wolston Park victims, even though commission representatives have briefly met with survivors.

While the Bligh government issued the Wolston victims a formal apology in 2010, the plaque commemorating the event, to be put on the wall of Parliament House for all time, was lost. In 2013, the Newman government read a renewed apology into Hansard, and a plaque was restored. (In one of numerous letters Barbara Smith sent to the premiers of the day, she got a reply from Campbell Newman in 2013. While he expressed his “sadness” over her story, “regrettably the Government will not revisit the issue of financial redress in the foreseeable future”.)

Seven years after the initial formal apology, the Palaszczuk Government has opened a “reconciliation process” with the victims. As the Queensland Department of Health explains, the Reconciliation Plan Development Strategy stems from the original 2010 apology where the government “undertook to plan formal reconciliation with those who were harmed”.

Having listened to victims “in a safe and respectful environment”, the Department of Health says it will then “meet with other relevant agencies … to develop an interim proposal for Government based on each person’s thoughts and ideas about a reconciliation plan”. That plan would then have to be approved by Government and, ultimately, implemented.

The Department of Health will also work with Mental Health Commissioner Dr Lesley van Schoubroeck through the process.

Encouragingly, the Queensland Government late last year passed new laws that removed the civil statutory time limit for child victims of sexual abuse, giving them the opportunity to sue those who had harmed them no matter how long ago the events occurred. Previously, victims had only three years from the time they turned 18 to mount court action.

But not everyone is convinced the new process, due to begin this month, will make any meaningful progress.

“I don’t have a lot of faith in it,” says Sue Treweek. “The problem I have with it is that in the apology they said they promised to work with us. But we’re the last to know anything. I’ve been lobbying for a long time. We’ve had a lot of these types of things, and I’ve never seen one like this, ever. It’s all closed doors.

“At the end of it all, all I see is that they’ve made no real commitment.”

Chenowyth says a full investigation into Wolston Park is required. “I don’t think it’s just about a reconciliation process or redress,” she says. “I think the Queensland Government needs to come clean and we need to have a public dialogue about this. And there needs to be rigorous research. There needs to be a public narrative and a proper investigation done. The current royal commission … that was an opportunity right there. They employ researchers, they don’t just conduct hearings. There is a whole research team and outsourced research to experts.

“The royal commission could have done this, you know? That was a lost opportunity. They’ve failed these women, I think.”

Given the “girls” were tortured and abused as children, and some are now in their 70s with poor health, is it fair to ask – is government, of whatever colour across the years, drawing this out and waiting for the victims to die?

“I think that’s a fair conclusion,” Chenowyth says.

On January 18, 1882, The Brisbane Courier reported – as it did regularly – on the “state of the asylums”. Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum, it said, contained 292 males and 213 females. It also revealed that one female patient had recently died. Isabella Lewers, native of Ireland, passed away from “exhaustion”. That sad ghost, Isabella, still locked up at Woogaroo more than 16 years after she was sexually assaulted by a warder, had been finally released from the asylum.

More than 130 years later, her living sisters are still fighting to be heard and recognised, and compensated for their tattered lives as former wards of the state.

“Women have committed suicide,” says Barbara Smith. “They’ve thrown themselves in front of trains. Been burnt to death. There are only seven of us left. I still have nightmares. I don’t sleep without a light on.”

Each of these women has generated a trail of official paperwork that stands as a permanent reminder of the abuse they were subjected to. Barbara has dozens of medical certificates and psychiatric reports deeming her psychopathic, uncontrollable, neurotic, violent, suicidal, sullen and hostile.

And there’s Sue, who is understandably sceptical about the upcoming “reconciliation process” with the State Government.

“My theory, my insight, is if they do resolve this with us, they’re admitting there was trauma and abuse at Wolston Park … people who had mothers, fathers, aunties, uncles, grandparents, friends, they’re all going to be asking the same question – what happened to my loved one?

“You know what saved me? And a lot of the girls don’t like me for this. But it was my faith. Whenever I was alone and at the bottom of the barrel, I mean right at the bottom, the one thing that was always there was that I felt the presence of Jesus. It was the one thing I could hold on to and say: ‘I have to make Him proud’.”

As for Sandra, she made her thoughts on this long fight for redress abundantly clear at a meeting of Wolston Park survivors late last year in a letter she read out.

She challenged the audience to go home after the meeting, lock themselves in solitary for a week and give the key “to a male member of your family that you trust for those seven days”.

“Can you trust them to feed you every day… ?” she asked the group. “Can you trust them to take you to the bathroom and not watch you go to the toilet? Can you trust them not to dope you up on extreme psychotic drugs that are supposed to be for the sole use of the criminally insane? Can you trust them not to do unknown sexual abuse and you find out by waking up with him on top of you?

“Can you trust them not to bring a friend to that solitary room and do unspeakable things to you that to this day cannot be spoken about and nearly sends you into the depths of depression when it comes to mind?

“Can you trust him not to give you multiple shock treatments and to not put foreign objects in your private parts when you come out from said treatment?

“It is cruel what happened to us but it is also cruel what is being done to us now by making us fight for so long.” Sandra concluded: “It is time to finish it.”

Over at the 450ha grounds of the former Wolston Park hospital complex, the flocks of cockatoos, down from Cockatoo Island in the Brisbane River just north of the site, will, as is their habit, erupt into a screaming session before they sleep for the night.

They did it a century ago. They did it last night. And they’ll be screaming again tomorrow. ■