Way We Were: Tablelands railway from Cairns to Kuranda haunted by brutal worker deaths

Today the Tablelands railway is a scenic tourism route, but during construction it claimed the lives of many hardworking young men who suffered horrific deaths, writes Dot Whittington.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It seemed a remarkable coincidence that at almost the same time, explosions 3km apart rocked construction of the railway line between Cairns and Kuranda late in the afternoon of Saturday, September 22, 1888.

It turned out both were caused by premature explosion of rackarock, an explosive developed in London a decade earlier and used as an alternative to dynamite.

At 77 cutting, powder monkey James Doyle, was working 18-20m up a steep slope when the rackarock became stuck. Against all rules, he tried to force it down with the end of an iron scraper, rather than the wooden rammer provided.

It exploded, showering the men working in the cutting below with earth and rock. They ran, but three were not quick enough.

It took 10 minutes for John Cull, Antonio Raffaele and Lisidini Dunouro to be pulled from the rubble. Raffaele had died instantly from a broken neck, Cull died from head injuries soon after and Dunouro lived about an hour.

Others were injured but Doyle escaped with just a few cuts and bruises.

Three kilometres away at the Bluff, William Rose and Aremegro Citroni were 9m up a slope setting 50 plugs of rackarock.

Again, the rackarock stuck. Rose, unlike Doyle, used a stick to push it down but it still exploded.

Rose and Citroni were knocked down the slope. Boulders rolled over Rose, severely injuring him and breaking his leg. Citroni fell at least 6m but was miraculously uninjured.

An inquiry found that the nature of rackarock was changed by heat and that in a hot climate, a “trifling concussion” would detonate it.

The two explosions coincided with the arrival of warmer weather.

The fatalities were not the first – or last – during construction of the Tablelands railway which was to serve the tin miners in Herberton.

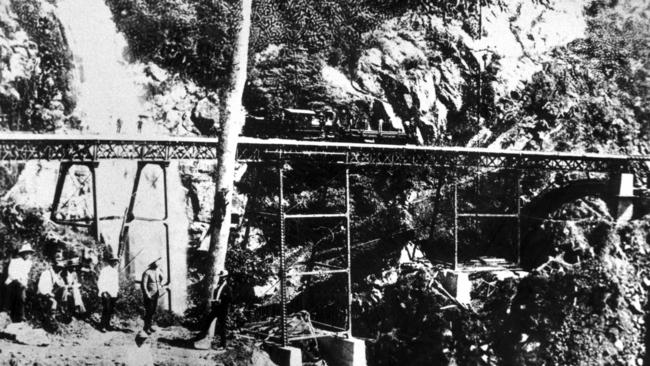

Cairns to Kuranda was the most challenging section, and remains an engineering miracle 130 years after its opening in June 1891.

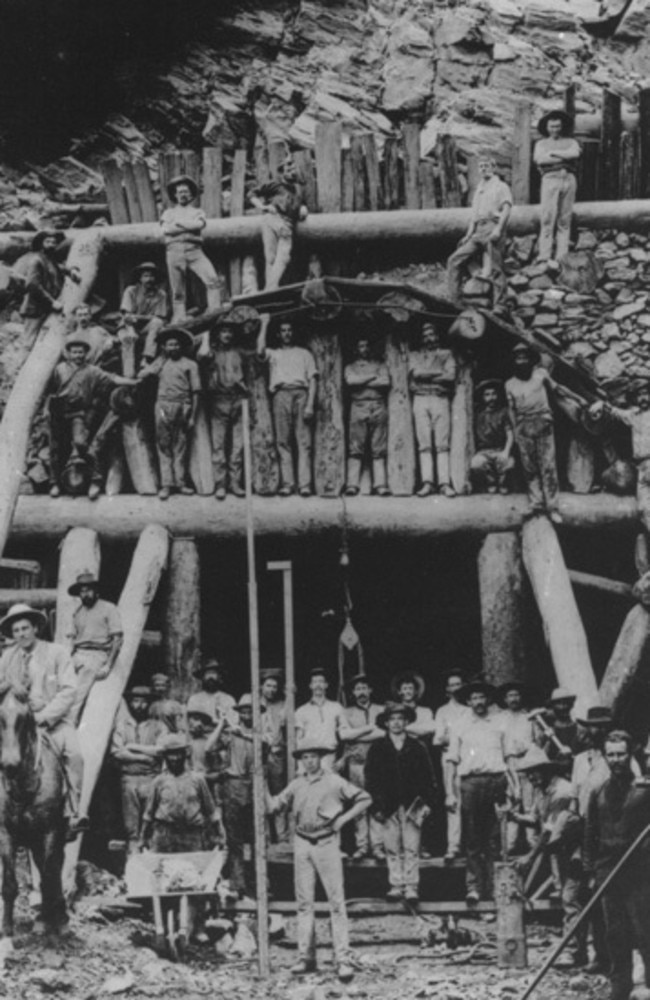

Now a scenic route for tourists to see the Barron River Gorge, waterfalls and lush vegetation as it snakes through 93 curves up the range, the line’s 15 tunnels and 37 bridges were built using hand tools, buckets and bare hands. At one stage, 1500 men, mainly Irish and Italian, were employed.

The work was hard and risky.

In 1887, Gavin Hamilton, a 23-year-old Scot, was clearing a gully at Beard’s Cutting when he lost his balance while trying to roll a heavy log into a raging fire in the gulch below.

Caught on the wrong side of the log, he was plunged headfirst into the blaze. Despite desperate efforts, nothing could be done. The cries brought other men down from the cutting who threw buckets of water on the flames.

“Hamilton was by this time charred to a cinder, but by means of a forked stick and a rope they succeeded in drawing his body out of the furnace,” it was reported.

Construction had started in May 1886 and by August, navvies were dying of fever and malnourishment in the camps that sprung up in Cairns.

William Bennett, 48, lay dying in a pitiful tent for more than a week and couldn’t get to hospital. He had been strong and healthy when he arrived to work on the line two months earlier.

It was three days before his body was removed.

Timothy Holland, 55, died three days later. He had a ticket for admission to the hospital but was rejected because he was in the employ of railway construction contractor P.C. Smith which had withdrawn its arrangement to pay Cairns hospital for sick workers.

A few months later, the death of another navvy prompted the Attorney-General to direct Smith to take immediate steps to prevent a recurrence of “so discreditable a state of things on the line under construction”.

With sickness prevalent and working conditions in the swamps and jungles approaching unbearable, Smith relinquished his contract after six months.

Work powered ahead as the line climbed the slopes but the tunnels took their toll. Two men were killed when earth collapsed, another was crushed by falling timber during a thunderstorm; and another when he was hit by a wagon of diggings.

The Barron Gorge section was completed in five years and cost almost three times the original estimate. By the time the railway reached Herberton in 1910, the tin mining boom was over.

The future of the hard-won range section was secured in 1936, when tourists recognised the value of the 37km Kuranda Scenic Railway.

Then, as now, the views of blue sea and forest-clad mountains “form charming photographs which are sure to be in demand in the metropolis”.