Indigenous community’s fierce fight for justice

After decades of struggle, Warwick’s indigenous advocates say ‘the time for being quiet is over now’.

Warwick

Don't miss out on the headlines from Warwick. Followed categories will be added to My News.

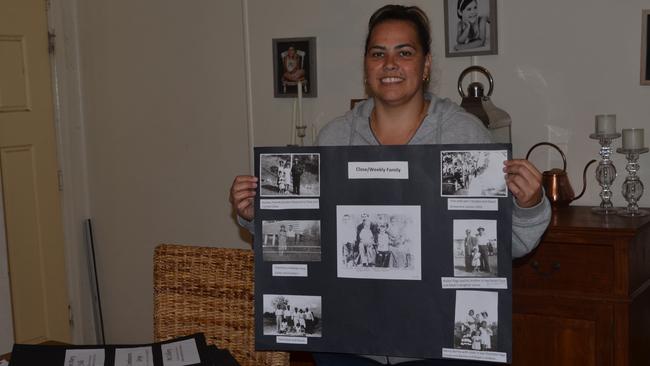

AS A proud indigenous woman of the Githabul tribe, Melissa Close Chalmers has spent years researching her heritage and connection to the land across the Southern Downs.

Ms Close Chalmers and other members of her tribe have spent years tracing their ancestry as part of their claim to Native Title, which acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ special rights over land occupied by their ancestors at the time of European settlement.

After these years of intensive research in conjunction with Queensland South Native Title Services, Ms Close Chalmers said her tribe was in the process of registering its own claim over the Southern Downs.

“Aboriginal people should never have to prove, and jump through hoops to prove, that this was their traditional land,” she said.

“You have to be able to prove your connection to an area, to make it that traditional land.

“For me, it’s for my ancestors more than for me, because it’s a kick in the guts to them.”

In 2007, the Federal Court of Australia recognised the Githabul people’s native title rights over 1120 sqkm of northern NSW.

As the Githabul tribe’s traditional land on the Southern Downs is divided from the NSW area by the Queensland border, Ms Close Chalmers said they had to surrender their part of the claim for it to go through.

As the native title case encouraged her to delve deeper into her ancestry within the Southern Downs region, it became clear to Ms Close Chalmers how little indigenous history is taught in schools and the wider community.

“I honestly think there’s a lot of people out there who don’t even know the history of their own country and what happened,” she said.

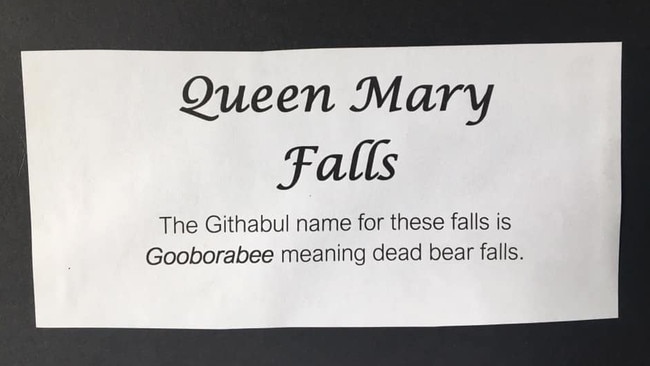

Ms Close Chalmers wanted to tell the history of Githabul place and town names across the Southern Downs, as it had been passed down to her through generations of storytelling.

In a post to Facebook group, The Lost Faces of Warwick’, she imparted that the Githabul name for Warwick is Waringh Waringh, meaning ‘cold place’, along with many others.

Ms Close Chalmers said her tribe’s native language was one of the most intricate and significant parts of her heritage, and something she would love to teach not only her four children, but also the region’s wider community.

“I can’t speak it fluently – our grandmother could, and she spoke it frequently – but every time I learn something new, I teach it to my children too,” she said.

“With the names of towns, I wanted to share it because I want to put my personal connection to this area so people know the truth.

“When we get native title, I’d love to have some street names or even towns with the Githabul name and meaning underneath or alongside the town name.”

Above all, Ms Close Chalmers said the most important thing was for the entire Southern Downs community to listen to indigenous voices and learn the region’s true history.

“There are people still living here today that have a blood connection to this area, so just tell people the true history,” she said.

“Schools teach the true history of other countries, so why not here?

“A lot of people in the community haven’t known anything because we’ve been quiet. The time for being quiet is over now, and to me that’s important.”

Standing alongside individual advocates like Ms Close Chalmers are those addressing racial inequality at a more systemic level, in areas such as health and medical care.

For Carbal Medical Services Warwick clinic manager Kerry Stewart, the disproportionately high rates of chronic disease within the local indigenous community are a reality she is faced with daily.

“Diet is the main cause, and a lack of physical activity, mainly as a result of lower socio-economic status and that sort of thing,” Ms Stewart said.

“We try and encourage all of our clients to have their 715 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health checks on a yearly basis, and to have their GP management plans in place.

“It’s a comprehensive health check that goes through everything. It’s trying to identify any issues as early as possible to either prevent them or reverse them to give a better life expectancy for our indigenous Australians.”

However, in a “major step forward” for indigenous healthcare across the region, the Federal Government recently injected almost $700,000 into the Timely Allied Health for Mob trial.

In a statement, Carbal CEO Brian Hewitt said the initiative, which will provide “on-site and culturally aware” access to a variety of allied health professionals, was a massive step forward for the organisation and its clients.

“All Aboriginal medical service providers identify that a major inhibitor of continuity of care and prevention of advancement to chronic disease is the restricted availability to our services of allied health services,” Mr Hewitt said.

“Carbal believes that this trial has the groundbreaking capacity to make a significant change and difference to the way that Aboriginal health is delivered nationally when replicated.”

For Ms Stewart, continued progress in healthcare for indigenous Australians could only be made possible through community engagement and intersectionality.

“We work pretty closely with a lot of the organisations within town, such as the schools, Centrelink, the hospital, and other GPs and medical practices,” she said.

“We’ve just started doing the NDIS here in Warwick, in the last six or eight months, and we’ve definitely seen pretty good success rates so far.

“We had one client who was denied three times, and when we helped them, they were finally able to get the funding they need.”

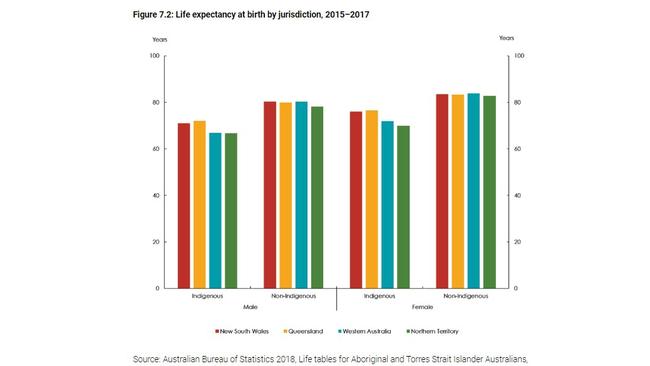

According to the Federal Government’s 2020 “Closing the Gap” report, indigenous Australians still live an average of eight years less than non-Indigenous Australians.

Even though Queensland reported the highest indigenous life expectancy in the country, with men around 72 years and women at 76.4 years, those of regional and remote populations were significantly lower.

Queensland has also reported “little or no improvement” in the rate of indigenous Australians’ mortality since 2006.