Wally Lewis autobiography: Key revelations from My Life

Wally Lewis has revealed just how close he came to committing suicide after his brain operation caused crippling depression.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Wally Lewis has revealed for the first time how he was conceived out of wedlock in the back of a truck and grew up poor, how controversial Queensland premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen made a bizarre attempt to recruit him to politics and that his concussion from football head-knocks as a kid was so bad, his mother would watch him sleep.

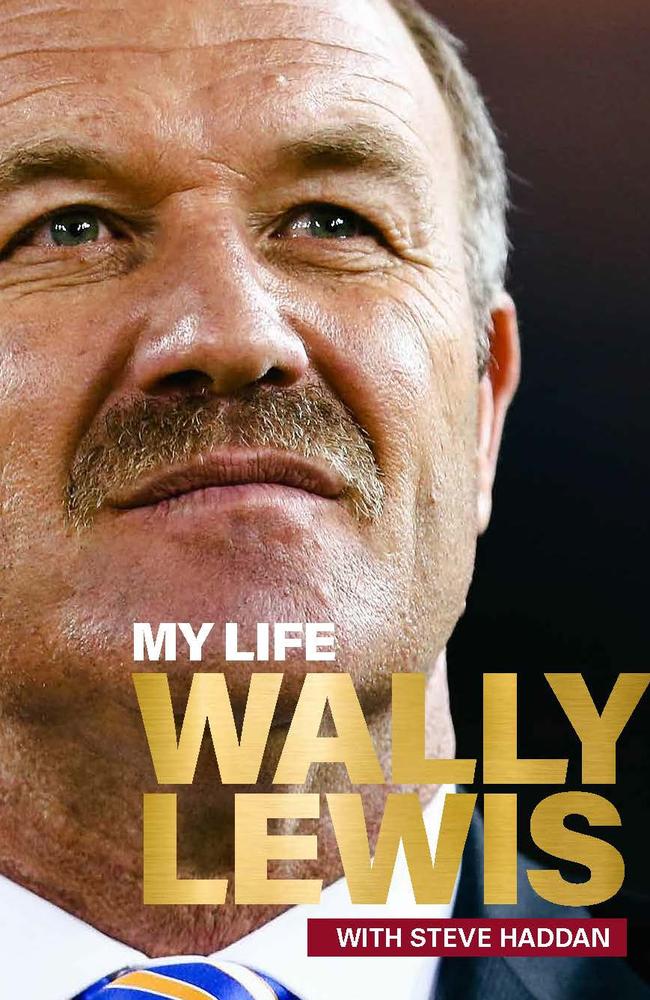

The incredible revelations have come to light in the rugby league legend’s autobiography My Life, released this week.

King Wally reveals his life, ‘warts and all’ in self-published autobiography

Origin 2020: Scott Prince on the moment Wally Lewis took his boots off

Lewis reflects on his career and how he wants to be remembered

When he set out to research his new book, Lewis assumed he knew everything about his own story.

That was until he quizzed his parents about their wedding day and a shock revelation knocked him down with the force of a Trevor ‘the Axe’ Gillmeister tackle.

The King – one of the greatest rugby league players of all time – was conceived out of wedlock one steaming hot Brisbane night on the back of a flatbed truck on Virginia Avenue, Hawthorne.

His mother June and father Jim kept the conception details secret until their 60-year-old son started asking questions for his book.

“Taking the trip down memory lane with my parents has revealed that contrary to what’s been previously reported, Mum and Dad were not married on 25 July, 1958, but exactly one year later,” Lewis says.

“That’s four months and one week before yours truly was born … Mum walked down the aisle at St Paul’s Anglican Church in Vulture Street with a bun in the oven!”

On discovering his daughter was pregnant, Lewis’ grandfather Jack Ballinger “hit the roof”.

“We had no money. Got a ring from Wallace Bishop across the road from City Hall. 100 quid. We had to pay that off,” Lewis’ father Jim says.

“Getting married was the natural thing to do. I did love her and I still do.”

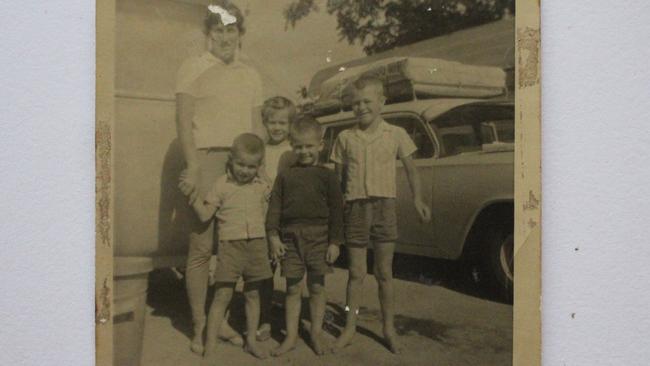

My Life details how a cheeky, working-class kid from Cannon Hill grew up into a rugby league immortal.

It lays bare the ecstasy of Valley Diehards and Queensland Origin triumphs, the agony as seizures took control of his life and the unbreakable bond of his devoted family.

But running through it all is Lewis’ unrelenting determination.

“When I was a boy, I thought you had to be superman to play first grade. An impossible dream. What I quickly learnt from my parents at a young age was that dreams don’t become a reality through magic. You have to roll up your sleeves and work at it,” Lewis says.

Co-author and former Nine Network sports presenter Steve Haddan described Lewis as “the world’s favourite Queenslander”.

But while he may be most familiar as the Emperor of Lang Park and the raging Origin mastermind regulating NSW’s Mark Geyer in that iconic 1991 photograph, there is more to Wally beyond sporting prowess.

In a Saturday Courier-Mail exclusive, here are five of the most explosive revelations from Wally Lewis: My Life.

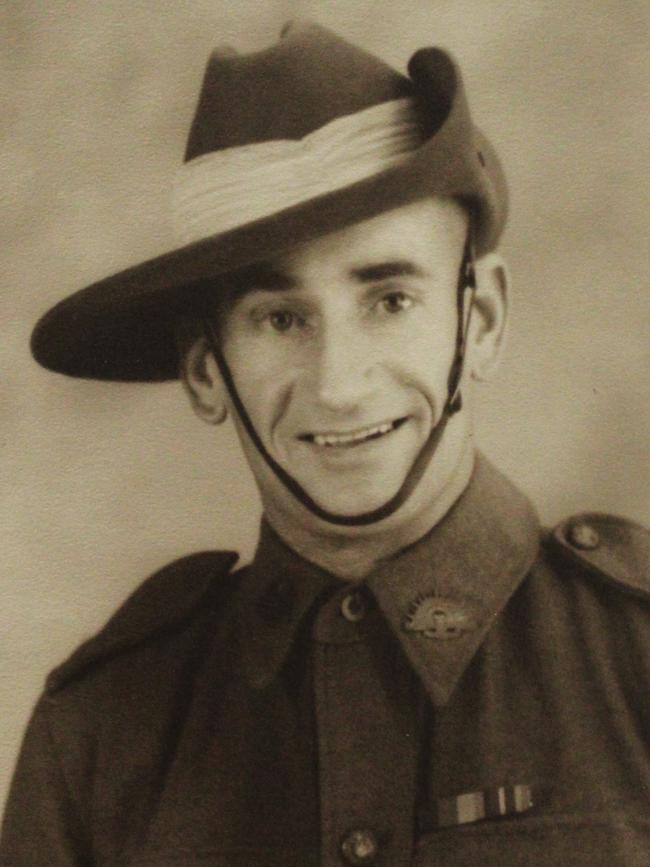

WORLD WAR II SCARS

In his opening chapter Bloodlines, Lewis details how his paternal grandfather Les, who lived in Petrie Terrace (a stone’s throw from the future site of Lang Park) was sent to the jungles of Guinea. He was “never the same” after his return. Les’ wife Daffodil Lewis left Brisbane to find work in the bush and abandoned her teenage son and husband for a man she met in Emerald. She had a daughter – Lewis’ half-aunt – Dianne who died aged 10 after her appendix burst.

The sadness of war and his broken marriage took its toll on Les, who in his later years struggled with alcohol and had his leg amputated from gangrene.

“His deterioration left its mark on me,” Lewis says.

“One day we visited and he hadn’t been out of bed for days. Dad told us to wait in the hallway while he cleaned him up. I remember the night in 1977 when Mum took the call at home that Les had died. I sat alone with dad on the front steps, with very little said.”

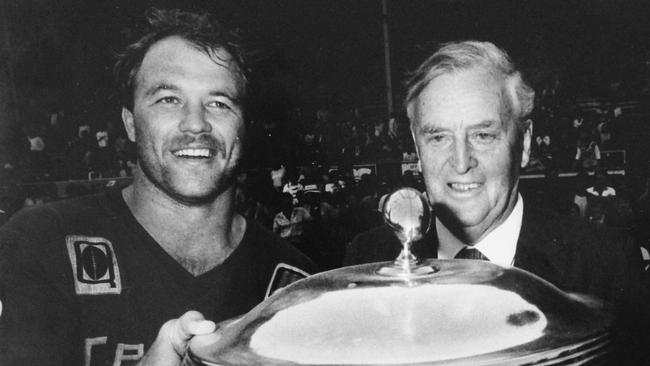

BRISBANE’S BRADMAN OF LEAGUE

Lewis grew up in a “humble house” in Cannon Hill, where the backyard was home to hours of football games with the neighbourhood kids.

“It was full tackle only at our place,” Lewis remembers.

But it was the back wall of the house that bears the marks of Lewis’ early talent.

Just as Sir Donald Bradman honed his cricket skills as a child in solitary games with a backyard tank stand and fence, Lewis finessed his ball prowess on the wall.

His constant thudding of the Steeden against timber stripped away the paint.

“To say I was obsessed with rugby league from a young age would be the classic understatement,” he says.

“I spent hours and hours passing and kicking to an imaginary target on this back wall … much to the delight of my mother, whose kitchen backed on to the wall. It’s a wonder it’s still standing.

“If you want to get good at something, practise, practise, practise and then practise some more.”

FINANCIAL HARDSHIP

“Money was tight” growing up, Lewis says, but the children never missed out.

“We were having too much fun to make any judgments about our circumstances,” he says.

“Dad scrounged extra cash wherever he could. All my brothers wore hand-me-downs. Mum crumbed lamb brain and told us it was fish. We rarely went to the city but we went to the Ekka every year.”

Most days the Lewis kids would walk to school bare foot, but Lewis recalls one morning when their mother drove them and suddenly pulled over and demanded they do a snap spelling test.

“Turns out she’d spotted a cop car at the bottom of the hill – and our rego hadn’t been paid,” Lewis says.

“‘We’ll be able to afford it next week,’ she told the officer, who let us go … You could actually see the road through the bottom of Mum’s car.”

SIR JOH TRIED TO RECRUIT WALLY

In 1984 Lewis was a league golden boy and then Queensland premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen wanted to use that appeal for his own political power.

The controversial premier summoned a 24-year-old Lewis to the Executive Building and attempted to manipulate him into contesting the state seat of Greenslopes for the National party.

“(Sir Joh) had a couple of heavies with him at the meeting, who revealed a dossier had been kept on my wife Jackie and father-in-law Bruce Green for their connections with the Labor Party and union movement,” Lewis says.

“I couldn’t believe what I was hearing and got out of there as fast as I could.”

BLACK DOG

Lewis copped numerous on field king hits through his youth — one so bad he ended up in the Mater Hospital and missed a month of football.

By the age of 19, the head knocks were becoming a concern. His mother was especially worried, bailing up blokes after matches if they attacked her son.

“Even as a junior he was a marked man, getting concussed all the time,” June Lewis says.

“I used to watch him in his bed while he slept.”

In 1980, at the age of 20, he had his first seizure while watching TV.

Lewis kept his epilepsy diagnosis secret from 1987.

Outside of his family, only Gene Miles, Paul Vautin, Wayne Bennett and Allan Langer knew of his daily seizures. All were sworn to secrecy.

Until 2006, when Lewis had a seizure on air during the Nine News evening sports segment. Having resisted brain surgery for nearly 20 years, Lewis finally underwent a four-hour operation in 2007. What he and wife Jackie hadn’t anticipated was the depression that followed.

“I had suicidal thoughts and found myself crying uncontrollably, for no reason,” he says.

“I needed someone with me at all times.”

Lewis also admits to coming close to killing himself at his Brisbane home when his wife had ducked out to the shops.

“Another time I walked down to the pontoon on the canal at the back of the house and considered jumping in,” he says.

“The thought was actually there – that day. If I was going to suicide that’s when I would have done it. (Jackie) never left me alone after that.”

Antidepressants helped Lewis get back to normal, he says.

He is astounded the damage – that he suspects was from blunt force trauma to the brain from football – has now gone.

“I wasn’t really expecting any significant progress for a couple of years but after 10 months I was back reading the sport,” he says.

“What was my secret? Lots of chocolate. I have not had a seizure since.”

My Life: Wally Lewis, $39.99 from QBD and Dymocks. Limited hardback signed copies, $59.99 at www.stevehaddan.com.au