Sick kids give their verdict on the Queensland Children’s Hospital

The Queensland Children’s Hospital has been mired in controversy since it was first announced in 2006. But what do the people who matter most, the sick kids, really think about their time in its care.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

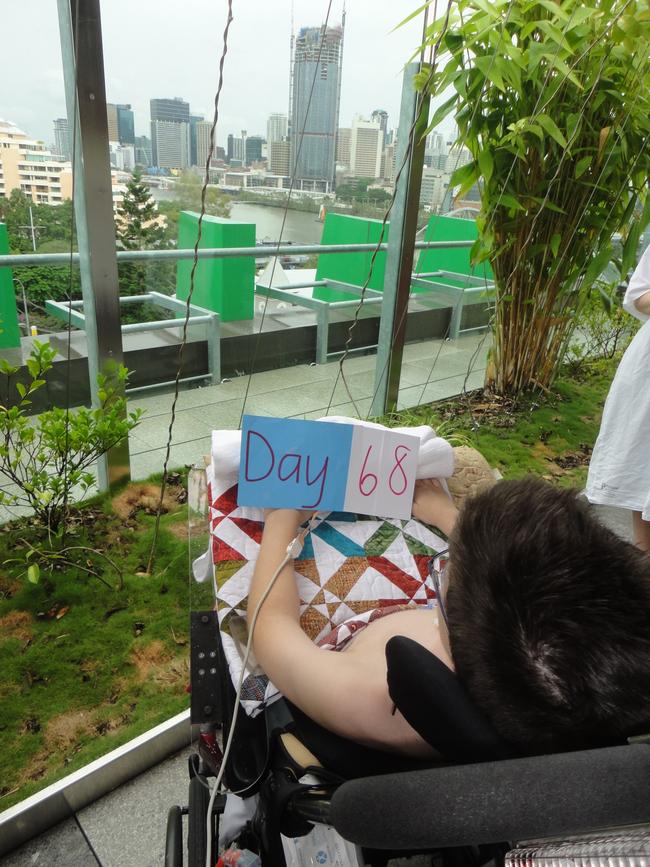

THIRTEEN-year-old Samuel Thorne has always had a competitive streak but he also holds a record no child would ever covet – for the longest stay at the Queensland Children’s Hospital.

Sam spent 480 days in the intensive care ward of the QCH after being diagnosed with an extremely severe case of a rare neurological condition, transverse myelitis. He went from being an active nine-year-old who loved swimming competitively, basketball and playing the cello to relying on a ventilator to keep him alive, barely able to move.

HAPPY TO FACE THE WORLD AFTER SURGERY IN BRISBANE

QLD CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL CANCER PATIENT MOURNS LOST FRIENDS

THE CANCER OFTEN MISDIAGNOSED AS A SPORTS INJURY

But when asked to reflect on the marathon 16 months he spent in the $1.5 billion standalone children’s hospital, which turned five this week, it’s not the traumatic days of medical treatment or the devastating news about his condition he focuses on, it’s the kindness of the staff.

“The doctors in the paediatric intensive care unit … always listened to what I had to say about how I was feeling,” says Sam, who was recently selected as Springwood High School’s junior vice-captain for 2020 and this year won awards for Year 8 English and Humanities and Social Sciences.

“The specialist doctors and therapists were always thinking about ways for me to be more independent and have more freedom.”

It was a physiotherapist at the hospital who suggested boccia, a Paralympic ball sport, similar to bocce, may be a good fit for Sam, who uses the small amount of movement he has in his right foot to drive his power wheelchair and has no movement in his arms.

“He said to Samuel: ‘I think you’d do really well at this because you’d be using your brain’,” recalls Sam’s Mum, Jane Thorne, who was by her youngest child’s side about 12 hours a day for all but one of the 480 days he was in the QCH.

Sam, who was discharged from hospital in March 2017 and has support workers 24 hours a day to help his parents care for him, is Queensland’s 2019 boccia champion for the BC3 classification – those who have severe dysfunction in both arms and legs.

He instructs his father, Craig, who must keep his back to the court, on where to place a ramp, which is used to deliver the ball.

“He can use the small amount of movement in his feet to release the ball from the ramp,” Jane says.

Doctors suspect Sam had a respiratory illness in November 2015, triggering an immune response that irrevocably damaged parts of his brain stem and spinal cord, leaving him a quadriplegic.

He continues to rely on a breathing machine to keep him alive and is fed through a tube into his stomach, because he has lost the ability to swallow.

The schoolboy can only speak because a “very helpful respiratory consultant” at the QCH investigated different tracheostomy tubes, finding one that allows Sam to use his voice after spending his early months in hospital, unable to talk.

“It’s a bit scratchy, but it’s clear enough to understand,” Jane says. “He has a microphone that he can wear to school if there’s an activity where he has to project his voice.”

After watching QCH staff care for her only son, Jane says: “I can’t fault them. The building is impressive, but it’s the people. We had a lot of wonderful souls looking after Samuel and help him be the best that he could be to take on the rest of his life.”

The Queensland Children’s Hospital opened on November 29, 2014, eight years after it was promised in the leadup to the 2006 state election campaign by then Labor Premier Peter Beattie.

For years it was mired in political controversy about where it should be built and even whether it should be built at all. The name has also created division, changing from the Queensland Children’s Hospital to the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital and back to the Queensland Children’s Hospital under governments of different political persuasions.

Melding the cultures of two existing hospitals – the Royal Children’s and Mater Children’s – into one was always going to be a challenge.

But five years into the life of the new hospital, Children’s Health Queensland CEO Frank Tracey, who has been with the service for four years and took over the head role in June from Fionnagh Dougan, describes the merger “as a success”.

“The most important aspect of our organisation are our staff,” he says. “We’re always thinking about how we can improve, how can we do better for families? We continue to invest in what we know delivers better outcomes. That includes investing in our staff, in their education and supporting them. We’re much more than bricks and mortar.”

Attached to the QCH in an adjacent building is the Centre for Children’s Health Research. Being offered a place on a clinical trial can offer families of sick children hope – not just the possibility it will help their child, but the hope that generations of sick kids will benefit in future. Even the knowledge that researchers are working on solutions for a devastating illness can be comforting to some.

“We’re globally recognised for our leadership in research into critical care, burns, trauma and for our work in cystic fibrosis and obesity,” Tracey says. “We have the most active clinical trials for oncology in Australia and New Zealand. We’re incredibly proud of that.

“When I talk to families, if I think about oncology, or I think about complex conditions, where children are going to be challenged, and may have their young lives shortened, they’ll always say: ‘We’re incredibly grief-stricken because it hasn’t worked out for us, but we’re delighted you can learn something from our experience and maybe this contributes to it being better for another family’. That’s such a wonderful gift.”

QCH cancer patient Maxwell Shearer has raised $115,000 for research at the hospital, hoping it will help other children avoid some of the side effects of the debilitating treatment he’s had.

The 16-year-old was diagnosed with ganglioglioma, a rare, slow-growing type of brain cancer, in August 2014. He had major brain surgery at the Royal Children’s Hospital to remove some of the cancer but still has five tumours in his brain and one in his spine being closely monitored by doctors in six-monthly scans.

Surgery was followed by a year of chemotherapy, most of it in the QCH. Since then, he’s grappled with impaired vision, short-term memory loss and crippling fatigue, legacies of his treatment.

“I don’t remember much from then but I remember parts of it where every single thing was a challenge – reading, writing, I needed to learn to do everything again, even walking and talking,” the Villanova College Year 10 student says.

“I remember how tough and how horrendous that really was. The only thing that’s going to make a change to that is research. If I can do anything to make a difference I’m going to do whatever I can because things just really need to change now.

“I don’t think I’ll ever stop trying to raise money. That’s so important to me. Every single dollar that goes towards child research makes a massive difference. I’ve seen it. It gives people a lot of hope.”

Max, who regularly returns to the QCH for appointments, describes the South Brisbane-based hospital as “a beautiful” place, mentioning the outside gardens as a relaxing place to meet up with friends.

“When you’re sick, you never really want to be anywhere. But if you have to be anywhere when you’re sick, the Queensland Children’s Hospital is probably the best place there is,” he says.

For his Mum, Michelle Taylor, it’s the care provided by the cancer team she singles out for praise, particularly Max’s oncologist, Dr Tim Hassall.

“When Max was first in hospital, he was there about eight weeks, in and out of surgery and intensive care,” Michelle says. “Tim saw us every single day. There was one night, about day 40, it was eight o’clock at night and I thought: ‘Oh, Tim’s not coming today’. It was a Sunday and I thought: ‘Finally, he’s home with his family’. Just as I had that thought, he put his head around the corner and said: ‘Hey, I just thought I’d quickly see you before I went home’. Tim never missed us or Max. He’s an amazing man.”

Since Sophie Leonard was the first patient to arrive at the QCH by ambulance in 2014, the facility has cared for 251,000 individual patients, including 198,000 hospital admissions, 344,000 emergency presentations and more than a million outpatient appointments.

More than 25,700 emergency surgeries have been performed and more than 65,400 elective operations.

Almost two million blood tests have been taken, more than 15,000 appointments have been completed using telehealth, 36 liver transplants have been done, 35 kidney transplants, 174 cochlear implants and 546 cleft lip operations.

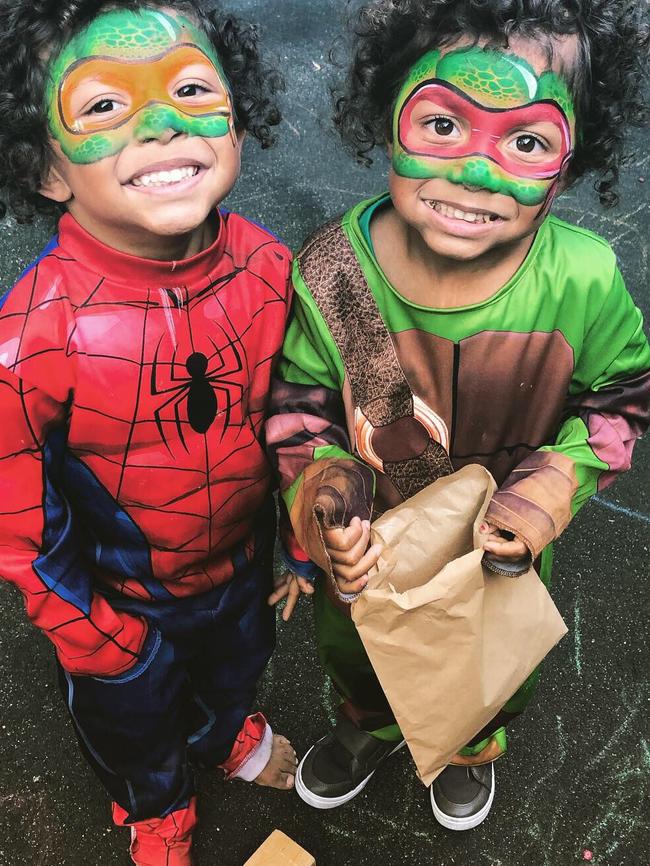

Among the first of 1474 cardiac patients were identical twins, Albert and Benson Tass, of Mackay, whose Mum Maria Cunliffe recalls them being born at the Mater Mothers’ Hospital during a raging hail storm, two days before the QCH opened.

Now five, the twins have both had open heart surgeries at the QCH after being born with complex cardiac conditions, detected in scans while still in the womb.

Their heart specialist, Dr Robert Justo, the QCH’s director of cardiology, said the move to a single children’s hospital had lifted the standard of paediatric heart care in Queensland “with outcomes equal to international best practice”.

“We’re caring for more complex problems and procedures than we were a decade ago,” he says. “We’ve got a very good platform to progress new therapies with an increased focus on research in this new environment.”

Frank Tracey’s vision for the next five years involves reducing the travel burden on families with sick children living in rural and remote parts of the state by using the QCH’s expertise to upskill general practitioners, paediatricians, rural generalists and other health workers outside the metropolitan area.

The QCH has signed up to Project Echo, developed by the University of New Mexico, aimed at improving medical expertise through the sharing of knowledge.

“What happens is we pull together a panel of experts so that other centres and other health professionals can dial in via videoconferencing and bring their cases and concerns in particular areas to the panel,” Tracey says.

“You’re also able to have experts from other countries join a panel. It’s an example of what the future looks like for us, when we talk about working with our colleagues and moving knowledge, instead of moving people.”

In the meantime, Max keeps fundraising to boost QCH research and Sam gets on with his life post-hospital, which involves the recent acquisition of a cavoodle he’s named Maggie.

•To donate to QCH research: childrens.org.au