Queensland’s landmark Forde Inquiry report 20 years ago was a turning point

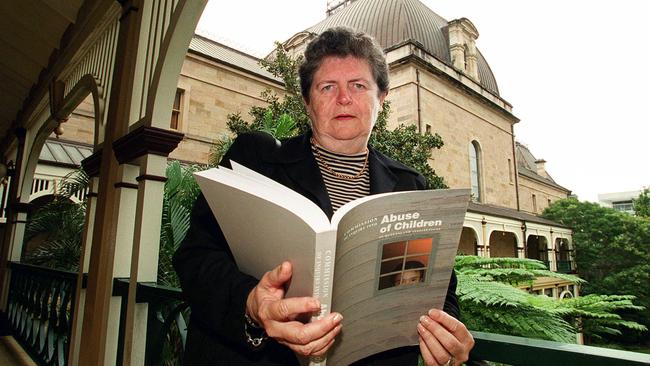

Queensland led the way with the Forde Inquiry into the abuse of children in institutions. Twenty years on, Leneen Forde, reflects on what was achieved by the groundbreaking inquiry she drove.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SHE always had a soft spot for orphans.

Way back in the 1960s, newly widowed, Leneen Forde would drive out to St Vincent’s Orphanage at Nudgee just before the Easter break with no appointment or official accreditation, ask for two or three kids, put them in the back of the family sedan and take them back to her suburban Brisbane home where she and her own five offspring would provide them with a taste of family life.

Decades later Forde, the former Queensland Governor whose groundbreaking child protection inquiry at the tail end of the 20th century created a blueprint for a host of investigations, including the 2013-17 child sexual abuse royal commission, was thanked by one of those kids who had managed, against overwhelming odds, to make a reasonable success of his life.

That man revealed to her a strange and heartbreaking truth about orphanage life.

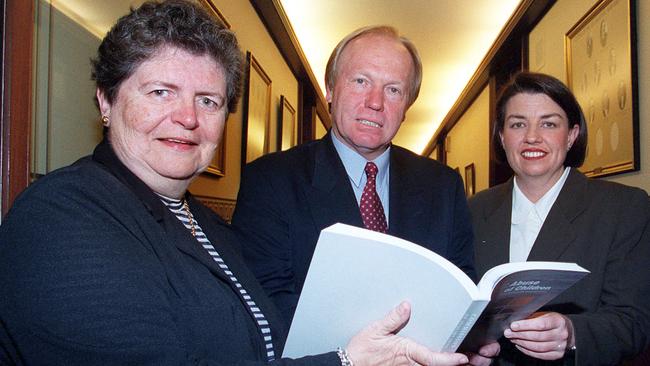

“He told me most of the kids didn’t actually make many friendships among themselves in the orphanage,” Forde tells Insight this week from her home at St Lucia, as she prepares to mark the 20th anniversary of her final report handed to then families minister Anna Bligh on May 31, 1999.

“But the kids who came to stay with us did form friendships because they had something in common, and some of them kept that connection right throughout their lives.”

That orphaned kids would spend a lifetime holding on to those precious few days in the Forde household, where they experienced a fleeting glimpse of the warmth, affection and security that so many us take for granted in childhood, is one of the more heartbreaking illustrations of the ongoing tragedy of our abandoned children.

Forde, now in her 80s, can at least rest easy that she did perhaps more than anyone else in this nation to ensure such children would not be subject to neglect, abuse, starvation or sexual molestation. The Forde inquiry, more than any other audit, prosecution, investigation or even royal commission in our history, transformed attitudes towards vulnerable children in Australia.

It ran for nine months between 1998 and 1999, examined more than 150 orphanages and detention centres operating between 1911 and 1999, heard horrific stories from around 300 people and produced a 380-page report containing 42 recommendations on child protection practices, financial redress and youth justice.

It’s genesis goes back to mid-1998 when Forde was holidaying in Canada with her second husband Angus.

The couple had briefly abandoned Queensland after Forde’s tenure as Governor had ended in 1997.

She and Angus were enjoying a break in Forde’s country of birth, giving the newly appointed Governor Peter Arnison some clean air to settle into his role, when Bligh called her and asked if she would head up the inquiry.

Forde, then into her 60s and with an extraordinarily busy life in medicine, law and public service as Queensland’s 22nd Governor behind her, hesitated.

And, at the time, media interest in the Canadian province of Newfoundland was becoming intense following the fallout from an inquiry regarding institutionalised children, and Forde remembers being utterly horrified and appalled, quite certain she did not want to involve herself in such a hideous world.

“I just remember thinking how awful it was,” she recalls.

It was Angus, the veteran homicide detective “with an extremely inquiring mind,” who convinced her to take on the challenge.

Though battling a terminal illness which would soon claim his life, Angus saw the worth in pursuing a matter that he was convinced required urgent attention.

Angus clearly possessed great foresight.

In 1998, the horror of child sexual abuse was only just beginning to crystallise in the public mind.

Just 13 years previously an American Dominican priest, Thomas Patrick Doyle, had authored a report on medical and legal issues raised by pedophilia in the Catholic priesthood.

Doyle warned of an approaching national scandal and presented his report to the United States Conference of Bishops, only to be ignored.

Twenty years ago even the word “pedophile” was to many Australians an obscure noun, not readily recognised and comprehended by many members of the public.

Forde accepted her husband’s advice, took a deep breath, rose to the challenge and, by August 1998, was back in Brisbane surrounding herself with a team which she credits with the success of her inquiry, and which included Queensland’s present Chief Justice Catherine Holmes.

The team’s first and greatest challenge was securing the trust of the victims, most of whom had been ignored (or even physically attacked) if they did have the courage to tell authorities what was being done to them.

“We had to convince them that we believed their stories,” Forde says.

“If they had told anyone in the past about what they had suffered, often they were simply not believed.”

That their stories might not be believed is, perhaps, understandable. Some spoke of an evil still almost impossible to comprehend by most.

One man, David Owen, who also told his story to the recent royal commission, was born as the result of a policeman’s rape of his 12-year-old mother in a north Queensland mining town, and deposited at the Neerkol orphanage near Rockhampton in 1939 as a five-month-old. There, during the 1950s, Owen was raped repeatedly by a priest, often after the Sunday Mass.

One of his few friends was a Sisters of Mercy nun known only as “Sister Emile’’ who would clean up the bleeding and comfort him after each assault, but who had no power to stop the attacks which continued over many years.

Forde’s memories of the horrors she heard also include the story of the Catholic priest who the Church had grown deeply troubled with because he kept molesting children, sparking parental complaints.

The Church tried everything (except calling the police) to deal with the problem, even sending the priest off to New Zealand where the offending continued, along with the complaints.

Eventually, someone within the hierarchy settled on the idea of sending the priest to St Vincent’s Orphanage at Nudgee, an institution utterly void of meddlesome parents who might raise the alarm about a priest molesting a child.

The priest was given the equivalent of an open license to attack children for several years, safe in the knowledge his victims had no one to turn to for protection. It was a courageous nun who eventually blew the whistle.

That cold, calculating and deeply cynical cruelty which would lead a church bureaucrat to place a monster among vulnerable children as some sort of “solution’’ to an internal problem still haunts Forde.

The human toll of those institutions is still incalculable, the emotional impact resonating for generations if victims did manage to establish a family.

“Many simply do not now how to love someone,” Forde says. “They do not know how to be a good father, mother, wife or husband. They often have to have an exceptional spouse to succeed.”

Child sexual abuse inquiries have exploded across the world in the 20 years since the Forde Inquiry, crossing international boundaries from Australia to the US to Ireland, where the Irish Government’s 2009 “Murphy Report” still resonates across the country.

In Queensland we have since had the 2004 Protecting Children inquiry into the abuse of children in foster care as well as the 2012 Queensland Child Protection Commission of Inquiry, overseen by lawyer Tim Carmody.

Forde says she is proud of the work of her inquiry but the achievements which stand out include shutting down the old, medieval institutions where so much of the abuse occurred, and creating a culture of child protection far more transparent and accountable.

Yet she is still acutely conscious that kids still are vulnerable.

Today, more than 12,000 children need some form of ongoing intervention from the state.

Last year 9406 kids were living away from home under the care of the Queensland Government, a worrying figure slightly exceeding the number of inmates in Queensland prisons. The research is also unequivocal on their fate – up to half the kids in state care can end up in the criminal justice system.

Karyn Walsh, a key figure in the inquiry and former Queensland Council of Social Service’s president believes Forde’s inquiry was ground-breaking, not least for establishing a new realm – one which she says the nation must continue exploring and expanding and monitoring.

The old Dickensian orphanages with their thin gruel and their bleak charity have disappeared, but the vulnerable child has certainly not.

Caring for abandoned or neglected children looks certain to become an even greater social challenge in the decades ahead.

It’s a problem Carmody neatly articulated during his 2011 inquiry when, faced with yet more frustrating and confronting evidence one afternoon, he muttered wearily: “You can’t legislate against bad parents.”

The Forde Inquiry began a process which must continue to be built upon.

As Walsh says: “We can never afford to cease being vigilant.”

michael.madigan@news.com.au

An event to mark the Forde Inquiry’s 20th anniversary is being held at the Queensland Art Gallery on May 31 at 11am.

Tickets at eventbrite.com.au