Why Bob Hawke said Paul Keating was his ‘best friend’

When Bob Hawke called Paul Keating his “best friend” it may have been somewhat of a backhanded compliment, but then again their story was rather complicated, writes Blanche d’Alpuget.

QLD Politics

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD Politics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN asked to update her Bob Hawke biography in 2019, Blanche d’Alpuget had no idea her husband would be dead within three weeks.

But it was information that came to light after his death that helped her reshape what she felt was a warped depiction of the relationship between him and Paul Keating.

Beneath the struggle for the prime ministership, as this extract shows, was a profound sense of respect between the two that never faltered.

HAWKE and Keating could often be seen hugging, holding tete-a-tetes, touching each other’s hands and arms with an easy rapport.

Their friendship now (after the Consumption Tax fight) was less overt, but it still ran deep, and intimate. In the future, this relationship would inevitably attenuate.

Keating had the intransigence of a born leader. Together with his personal charm, his ferociously held convictions gave him powers of salesmanship of extraordinary force, and slowly this force would be brought to bear upon the Caucus.

Like Hawke, he had been convinced since youth that he would one day lead the nation.

Unlike Hawke, who enjoyed discussion but not talk, Keating was a relentless talker whose telephone calls to journalists and editors would sometimes stretch to an hour.

Hawke was the most popular prime minister in polling history, even after five years of hard reforms, and Keating was highly unpopular.

Hawke, as was his custom with bad news, chose to ignore it. He dismissed reports of Keating’s remarks as gossip he did not want to hear. Publicly, he and Keating were a brilliant team; privately they continued to talk to each other as intimates, Hawke fretting about Keating’s health, particularly his tinnitus, a cruel affliction for a man who so loved classical music. It was sections of the staff in both offices who were at fault in stirring trouble.

Hawke told Keating he had, with time and effort, established himself as an Australian leader who could play a constructive role internationally and he intended to do so right through until 1990. Keating said Hawke was neglecting leadership at home, and that if he had to keep being Treasurer until then, “I’ll be going ga-ga.”

But by 1988, Keating’s “bacon budget” was transforming into a live and greasy pig. It was not his fault: both the Treasury and the Reserve Bank had badly miscalculated. They had all predicted lower inflation and a lower current account deficit. But both were rising.

Catching the budget pig was going to be tricky and potentially dangerous.

Keating spent much of (that) September abroad, during which he contemplated his future. He had failed to bluff his way into The Lodge and the Caucus was not supporting him, but as he believed in his bones he was destined to be prime minister he decided to take the option Hawke had offered: a handover after the 1990 election.

Keating decided he must nail Hawke down to a promise, witnessed by another, for the deal to stick or else Hawke would string him along until he was totally worn out.

It was impossible, even for Keating, not to recognise that Hawke’s well of stamina was almost inexhaustible and that his skills of evasion were similar.

It took more than a month before Hawke could find time in his diary for a meeting with Keating.

Finally, on the evening of 25 November 1988, three gravefaced men arrived at Kirribilli House, the Prime Minister’s Sydney residence. They were Keating and his witness, Bill Kelty, secretary of the ACTU, and Hawke’s witness, Sir Peter Abeles. The deal was that Hawke and Keating would work as a team until the 1990 election, which Hawke expected to win; then, after a suitable time, but before the end of 1991, he would step down.

Keating would then, after the formality of election by Caucus, become prime minister. Hawke’s one proviso was that if the deal were leaked it was null and void. Keating agreed. Nothing was put on paper.

For the Treasurer, the Kirribilli pact was a disappointment: his “Paris option” card had not worked and the thing he had wanted so fervently to avoid, spending another two years grinding figures, while his wife and four children lived in a cramped Canberra house, would have to be endured.

For Hawke it was a triumph. He could ignore the relentless pressure of news media and staffers and look forward to clear air for steering the ship of state. He could afford one or two (or three or four), discreet affairs.

Keating, for his part, manfully accepted the setback, but his language showed how psychologically rattled he had been: he made a weird, vehement attack on John Howard, likening himself and Hawke to a pair of black widow spiders weaving a web to trap the leader of the Opposition.

To Keating’s great credit, although he knew of Hawke’s womanising and, as a devout Roman Catholic husband, no doubt deplored it, never did he use this knowledge to attack the Prime Minister.

Two weeks after Hawke won the 1990 election, the Opposition threw out its leader, Andrew Peacock. On 3 April it installed in his place an economist. The new leader of the Opposition, John Hewson, was a shiny, sharp cobra of a man. He drove fabulous cars and was known as “Fast Lane”.

He was a political greenhorn, which of itself made him interesting for the gallery. He was far more exciting than the greying team that ground out government business day after day.

While Keating was fourteen years Hawke’s junior, Hewson was almost twenty. In April, Hawke enjoyed his greatest pleasure and his final moment of peaceful reflection as Prime Minister when, at break of day on the 25th of the month, he stood with a handful of Australian and Turkish veterans and thousands of young backpackers above Anzac Cove to honour the dead of seventy-five years earlier.

Former enemies embraced; the young embraced the aged. It was a moment of human brotherhood, as if an age of peace yet to dawn had cast its soft light backwards onto the turbulent present.

A few weeks later Hawke suffered a private setback that temporarily did his standing as much harm as his world record in beer drinking had served him well over decades.

He needed a prostate operation. The fact was widely reported. Suddenly, the leader who embodied the Aussie larrikin ideal of boozing, playing sport and womanising transformed into the image of the male terror of impotence.

The medical procedure was minor, but at the time prostate operations of any kind were relatively rare, and frightening. While the press gallery restrained themselves in what they wrote, what they said to each other was as vulgar as it was vicious.

Three months earlier Hawke had been “still young”. Now John Hewson referred to him as “old” and “losing his grip on the party”.

The Keating-for-PM machine fired up again. Glenn Milne wrote in The Australian on 7 June: Consider some of the headlines generated in recent weeks … “Time may be right for Hawke to go”. “Keating shows the troops who’s boss”. “Hawke opens up leadership issue in quelling row”. “Hawke is on trial” and the doozy of them all, “Crusher Keating: How desperate is he?”

But then it fell into a ditch when the UN voted to militarily reverse Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Led by Hawke, Australia was going to war – and, as Hugh White, the defence analyst, noted, “In wartime, the Prime Minister becomes the King.”

By December 1990 enormous numbers of armed forces from all over the world were gathering on Kuwait’s borders. The terrible days of waiting began.

For Keating, too, they were days of waiting that became unbearable. On 6 December his head of department, Chris Higgins, a man of whom he was very fond, and who was just a few months older than Keating, suddenly died. The following evening Keating was to address the annual Press Club dinner.

He arrived in an emotional state, a Hamlet mood, and after a few jokes, launched into a rambling but fascinating tour d’horizon of how he saw the world, Australia, leadership and Australia’s leaders.

“Leadership is not about being popular, it’s about being right. The trouble with Australia is that we’ve never had (a great leader). We’ve never had one leader, not one, and it shows.” Curtin, he said, was a “trier”; Chifley “a plodder”.

Keating’s speech was off the record. Next morning Hawke received a full report of it.

The Treasurer’s timing could scarcely have been worse. Hawke was himself nursing a private grief: his greatest love, his father Clem, who had suffered a minor stroke earlier in the year, was fading towards death, while Hawke was emotionally keyed up to shoulder the burden of sending scores of young Australians into harm’s way with the distinct possibility of some returning in coffins.

On Monday morning Keating publicly performed a mea culpa, saying he had intended no disrespect to past or present Labor leaders.

Headlines read, “Keating Speech Puts New Strain on Ties with Hawke”, “Can They Last?” and “Labor’s Love Lost”.

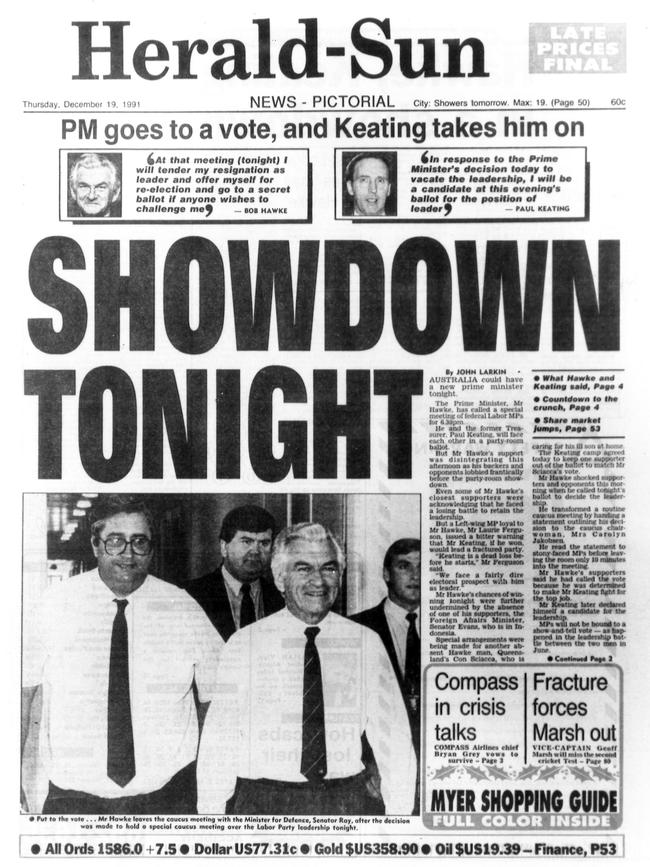

With the liberation of Kuwait, the warrior King shrank back to the news media’s loathed Prime Minister, and the Keating-for-PM machine roared into life. In December 1991 the Caucus rejected Hawke as Prime Minister to install Keating in his place.

A period of intense anger, bitterness and introspection followed, and without the magical glue to public life, power and privilege – and, most significantly with Hawke’s abandonment of his thirteen years of teetotalism – the Hawke marriage began to falter.

In November 1993 he left home and in July the following year married his long-term beloved, the writer, Blanche d’Alpuget.

One of the first effects of being happily remarried was that he forgave Paul Keating.

Hawke hated losing at anything, being so intensely competitive that while waiting for a lift he would bet with his driver or his secretary on which would arrive first.

It took him many years to tell Keating to his face that he was indebted to him, although he often remarked privately, “Paul is my best friend. If I’d stayed PM I couldn’t have married Blanche.”

This sounds a backhanded compliment, but it was sincere: somewhat shamefaced, he saw Keating as the agent of Providence, an essential goad into the next and happiest phase of his life.

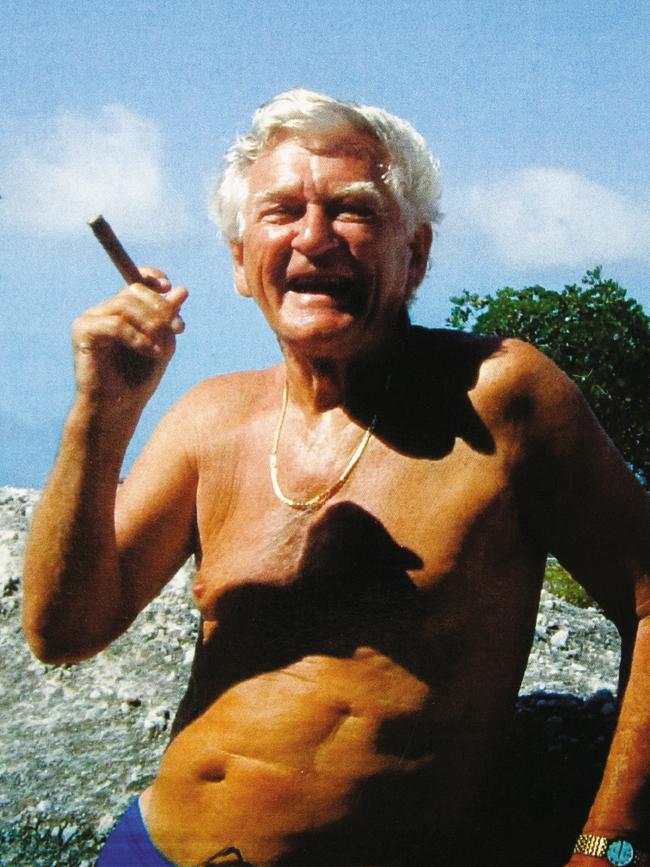

It was a tacit admission of his own hubris and irrationality in clinging to office longer than he should have. His tenacity could be almost superhuman: on holiday in Far North Queensland he fought a 300-pound bottom-dwelling shark known locally as a “Lazy Mary” for four hours, on a handline, finally dragging it to the surface, where he set it free. He was seventy-two years old.

In a principled political fight tenacity was one of his highest virtues, but misapplied it stagnated to pig-headed folly – as in the struggle against Keating.

Among Hawke’s greatest joys as he entered old age was that he and Keating renewed their bond of camaraderie.

One day Craig Emerson, who was a frequent visitor, asked, “Would you like me to try to bring Paul around to see you?” Emerson recalled, “Bob looked at me with childlike joy and anticipation on his face and said, ‘Could you’?”

Their reconciliation was an unalloyed success.

They spoke of how few were their disagreements until the leadership challenge, and afterwards Keating reiterated how close he and Bob were.

They talked politics, at some point agreeing that Keating would draft a statement of support for the ALP and Bill Shorten that he and Hawke would sign for a forthcoming general election.

Both were keen to have it known they had reunited, as they recognised it as a healing of the rift in the party their struggle had caused.

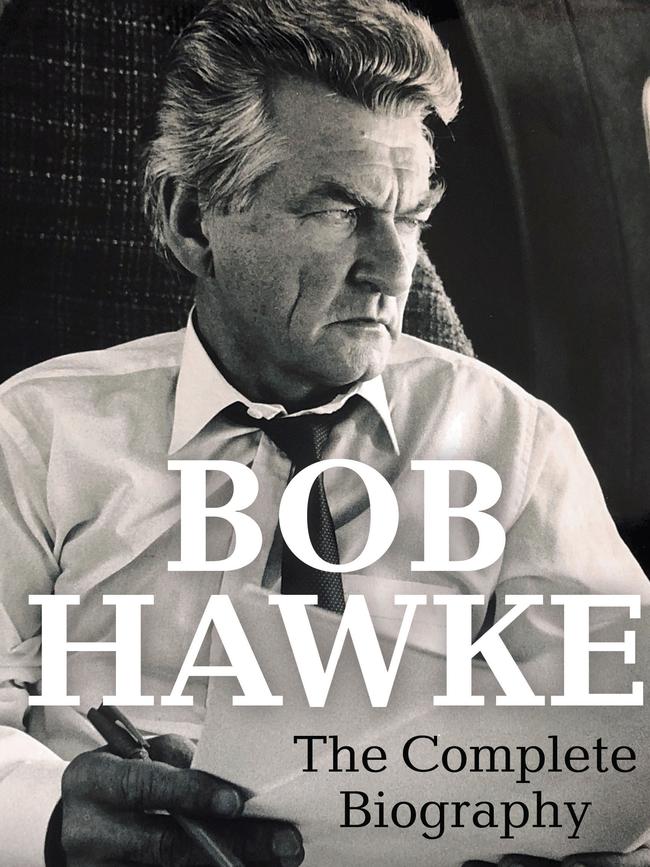

Edited extract from Bob Hawke: The Complete Biography by Blanche d’Alpuget, published by Simon & Schuster Australia, hardback, RRP $59.99