Jailed journalist calls for Qld shield laws

A former Queenslander jailed for observing his duty as a journalist says it should not take another to face the same fate before the state catches up with the rest of the country.

QLD Politics

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD Politics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A former Queensland journalist jailed for refusing to give up a confidential source says it should not take another to face the same fate before the state catches up with the rest of the country.

Joe Budd’s call for change comes 28 years after the then state Labor government reacted to his jailing by moving toward protecting journalists from being imprisoned for protecting their sources before it fell off its agenda.

Opinion: Qld long overdue for shield laws for journalists

Shield laws: State Government to consider reforms to protect journalists

LNP’s vow on journalist shield laws

“Hopefully it won‘t take another journalist going to jail to spark action,” Mr Budd said from the US, which he has called home since being released.

“Any political party that cares about democratic principles should support press freedoms, including shield laws.”

It has now become a state election issue, with the Opposition committing to adopt shield laws if it wins next month’s election amid a campaign by the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance.

Labor’s Attorney-General Yvette D’Ath has responded by agreeing to consider shield laws for journalists, but has so far refused to commit to their implementation if elected.

That is despite the Commonwealth and every state and territory in Australia changing their laws years ago to offer protections to journalists from being compelled to reveal confidential sources.

University of Queensland journalism professor Peter Greste, who spent 400 days in an Egyptian prison in 2013 for reporting the news, said Queensland was clearly out of step with the rest of the country.

He said the should adopt the Victorian model, which provided the strongest protections for journalists’ sources.

Mr Greste, who is also a director at the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom, said the Victorian model not only shielded journalists’ from having to reveal their sources during court hearings, but also during police investigations into the sources of leaked information.

“We know from the research that we’ve been doing here at the University of Queensland that the (Australian Federal Police) raids had a very chilling effect on the relationship between journalists and sources,” he said.

“A lot of sources dried up. A lot of sources told journalists that they are too afraid to co-operate and pass information to journalists.

“I think the evidence is quite clear that unless sources do feel protected then they are much less likely to come forward and I think that does have an effect on transparency and accountability in Government.

“If you recognise the need to protect that journalist source relationship in court, then that principle needs to run all the way through the process, from investigation through to the court case.

“And I think ..to emphasise that that does not mean that relationship must always remain confidential, but there needs to be a compelling case that should be up to the police to demonstrate why they need access to that information before they get a warrant.

Under the shield laws interstate, anyone seeking to uncover a confidential source must apply to the courts and prove that forcing a journalist to give up their source had a greater public interest than them not being named.

Changes were first recommended by the Australian Law Reform Commission in 2005, with every other state and territory, except Queensland, adopting specific shield laws for journalists between 2011 and 2018.

It recognises journalists would otherwise face being jailed or fined for upholding their profession’s code of ethics by maintaining the confidentiality of sources.

Shield laws have already protected confidential sources from being named interstate, including in 2015, when they were relied on by The Age newspaper in Melbourne to block a court application by accused mafia boss Antonio Madafferi to compel a journalist to reveal his sources for a story.

Debate over the lack of shield laws here erupted after an attempt by the Palaszczuk Government to rush in laws before the October poll that would have made it an offence for journalists to report on corruption allegations against candidates during an election campaign. It was abandoned a day later amid a public outcry.

Calls for shield laws gathered pace after the Supreme Court in August refused an application by a journalist, who cannot be named for legal reasons, to stop the Crime and Corruption Commission from compelling him to answer questions during a “star chamber” coercive hearing.

The court rejected the journalist’s claim that the identity of confidential source was privileged.

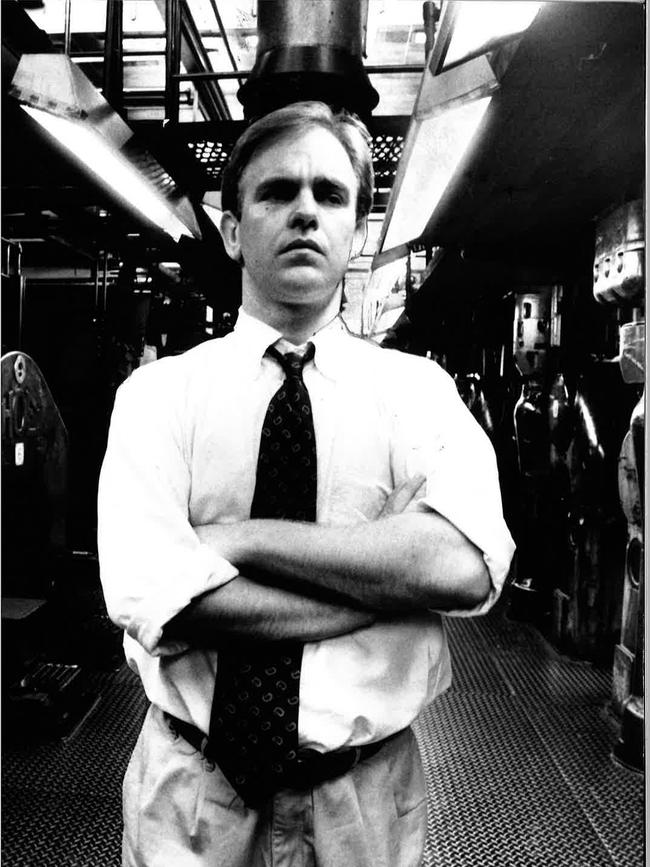

It comes decades after Joe Budd, then 30, spent four days in jail in 1992 for refusing to name a confidential source quoted in a story published in this newspaper on an alleged cover-up in the wake of a booze-fuelled police “rampage” in Toowoomba.

He was the second Australian journalist jailed for contempt of court for refusing to name a confidential source, with others journalists later hit with prison time and criminal convictions.

Mr Budd, now 58 and living in the US with his wife and two daughters, said shield laws to protect journalists’ confidential sources was “long overdue” in Queensland.

It needed “a champion in Labor” to take up the cause, he said, adding it was “odd” only the State Opposition had committed to the legal change and not Labor given its reform record following the Fitzgerald inquiry into police and political corruption more than 30 years ago.

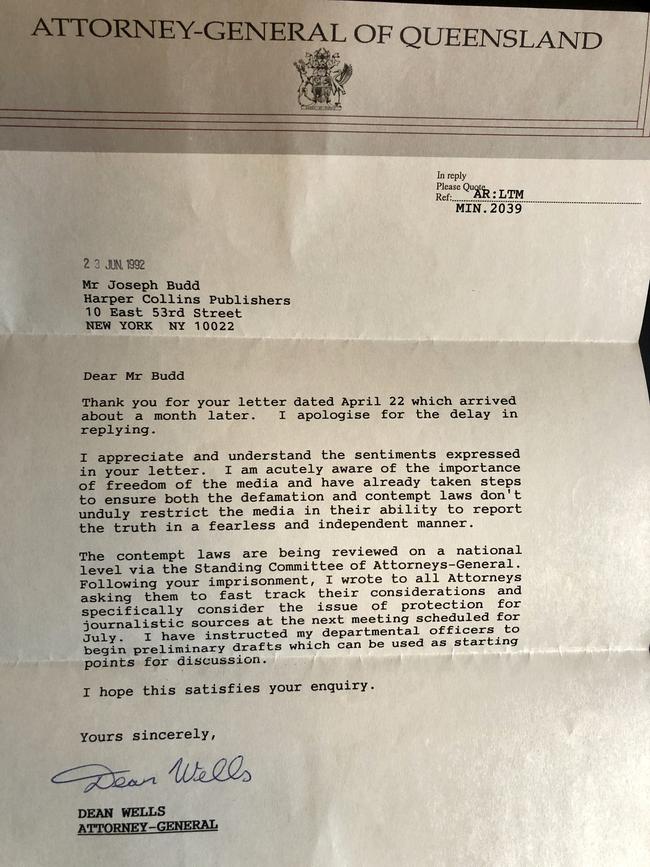

The absence of shield laws in Queensland comes despite Labor Attorney-General Dean Wells obtaining Cabinet approval in 1991 to pursue legal protections for confidential communications.

But the agenda faltered and there appears to have been no further attempt to overhaul the laws since.

Mr Budd exchanged letters with Mr Wells after his jailing, but said nothing came to fruition.

In a letter to Mr Budd after his release from jail, Mr Wells wrote that he had instructed his department to begin drafting amendments that would be a “starting point” for discussions with his counterparts across the country as part of a national review of contempt laws.

He said he had written to all the Attorneys-General asking them to “fast track their considerations and specifically consider the issue of protection for journalistic sources” at their next meeting.

“I am acutely aware of the importance of freedom of the media and have already taken steps to ensure both the defamation and contempt laws don’t unduly restrict the media in their ability to report the truth in a fearless and independent manner,” he wrote in 1992.

Mr Budd said the support from Dean Wells at the time was a positive but “didn’t translate into specific action”

“If you don’t seize the moment, then issues like these quickly lose traction,” he said.

His 2570-word “code of silence” report in 1989 had uncovered accusations of witness intimidation and a police cover-up following a drinking spree by police in Toowoomba during a football carnival.

At least 50 police officers had “rampaged through pubs, motels and restaurants, assaulting people and destroying property,” according to the report, triggering an inquiry that led to 15 charges against nine officers. The report focused on why none of the police ended up with convictions.

One of the police prosecutors named in the report successfully sued for defamation three years later, with Mr Budd – by then no longer a journalist and living in the US – returning to testify.

His jailing for contempt of court for refusing to name a confidential source during the defamation proceedings before then-Supreme Court Judge John Dowsett came as a shock twist in the case.

Justice Dowsett had pressed Mr Budd to identify an unnamed public servant he had quoted, saying it was a “more than a reasonable way of testing credibility to insist upon identification of (a) source.”

Mr Budd refused based on his ethical obligations as a journalist to respect source confidentiality.

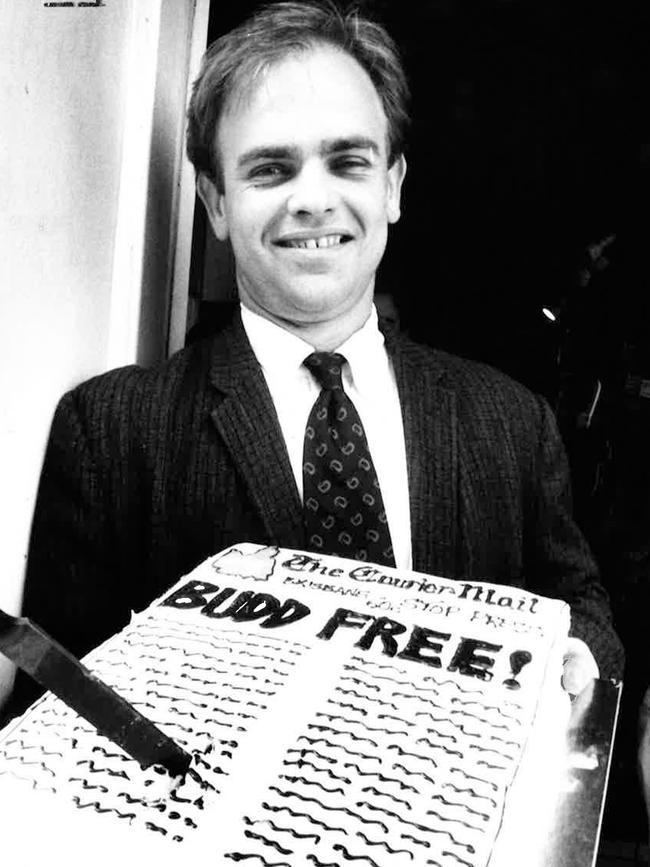

He would spend four days at Boggo Road jail for contempt of court in a decision that sparked a rally in the street and campaign for legal protections for journalists from having to reveal their sources.

Mr Budd, who had just turned 30 when jailed, reflected it was “not an experience I care to repeat, but I wouldn’t do anything differently if it happened again.”

“The journalist code of ethics was drilled into me from the first time I set foot in a newsroom and something I respect to this day,” he said.

“Courts put journalists in untenable positions in situations like this. I should have been the last Queensland journalist to face legal consequences for not revealing a source. Australia still ranks well down the list of countries for press freedoms —you have to ask, “what type of society do we want?”

His jailing came two years after Perth-based journalist Tony Barrass became the first reporter jailed for refusing to reveal the source of a story on malpractice in Australian Taxation Office.

Greg Chamberlin, who was the editor of the newspaper at the time of Mr Budd’s report, said it was “an embarrassment” that Queensland was the only state yet to adopt shield laws for journalists.

Just a few years before Mr Budd’s jailing, Courier-Mail journalist Phil Dickie was being pressed to reveal his sources by barristers for accused police and criminals to identify his sources at the Fitzgerald inquiry.

The Inquiry led to four ministers and a police commissioner being jailed, and Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen charged with perjury – dropped after a hung jury.

“As we are obliged to do, I refused,” Mr Dickie told the newspaper this month.

“It’s a bit daunting to be sent outside the room while they discuss your fate inside,” he said.

Inquiry head Tony Fitzgerald ultimately did not compel journalists to name their sources.

Mr Dickie was instead requested to approach his sources and ask them to independently approach the 1987 inquiry.

But Mr Dickie said Mr Fitzgerald position in that case “doesn’t obviate the need for journalists to be given some general protection for their sources”.

“I’m disappointed that governments of both persuasions in Queensland have not got around to implementing (shield laws) in line with what now seems to be a national law,” he said.

“When you are dealing with topics like organised crime and you promise confidentiality to your sources you are morally obliged for their safety to keep your promise, whatever the legal consequence.

“Even if they are given protection, journalists aren’t exonerated from having to inquire into the truth of what their sources tell them, or from sort of wondering what their sources motivations are.

“The other thing that journalists should not do is give the privilege of protected source to public figures who are flying kites or dishing out the dirt on their opponents.

“That’s an area where journalists can undermine their right to legal protection by mistreating the privilege so I caution against that.”

Not all in the industry agree with the need for shield laws.

Former Courier-Mail and Sunday Mail editor Des Houghton said this month he was “not convinced that journalists deserve to have shield laws.”