Quarantine ‘death spiral’: Premier’s school mate takes life after pleas ignored

Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk’s school mate was desperate. Spiralling with suicidal thoughts while locked in hotel quarantine, his family frantically tried to get him help. But it was ignored by Queensland Health. Then he took his life.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The family of one of Annastacia Palaszczuk’s childhood friends has revealed he took his own life after a hotel quarantine debacle in which Queensland Health ignored at least eight warnings he was gravely ill.

The “horrific and preventable” death of Brendan Luxton has prompted his grief-stricken family to slam the Premier quarantine system and demand the state’s “deeply flawed” quarantine exemption process be urgently fixed.

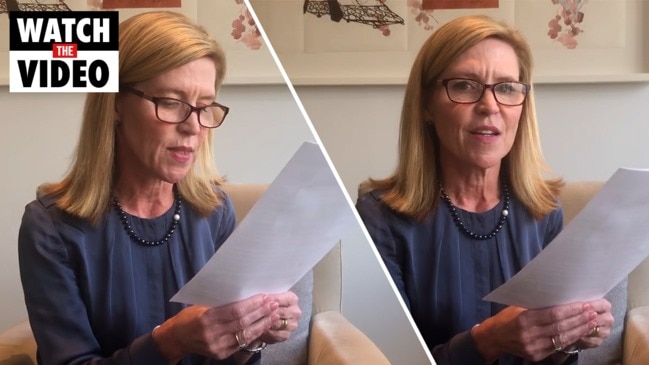

His sister Marita Corbett and younger brother Derek Luxton also claim Ms Palaszczuk – who has refused their plea to meet them personally since the tragedy – “opportunistically used” her friend’s death for political gain by mentioning him during a mental health funding announcement at a business lunch.

The family has broken their silence after Ms Palaszczuk admitted this month the Queensland Health exemption unit “needs to work a bit harder” while refusing to grant home quarantine to the family of a desperately sick infant.

“The lack of compassion and common sense from this government is galling,” Mrs Corbett said.

Her family has also released dozens of texts and damning documents from Queensland Health which show Brendan’s case was ignored.

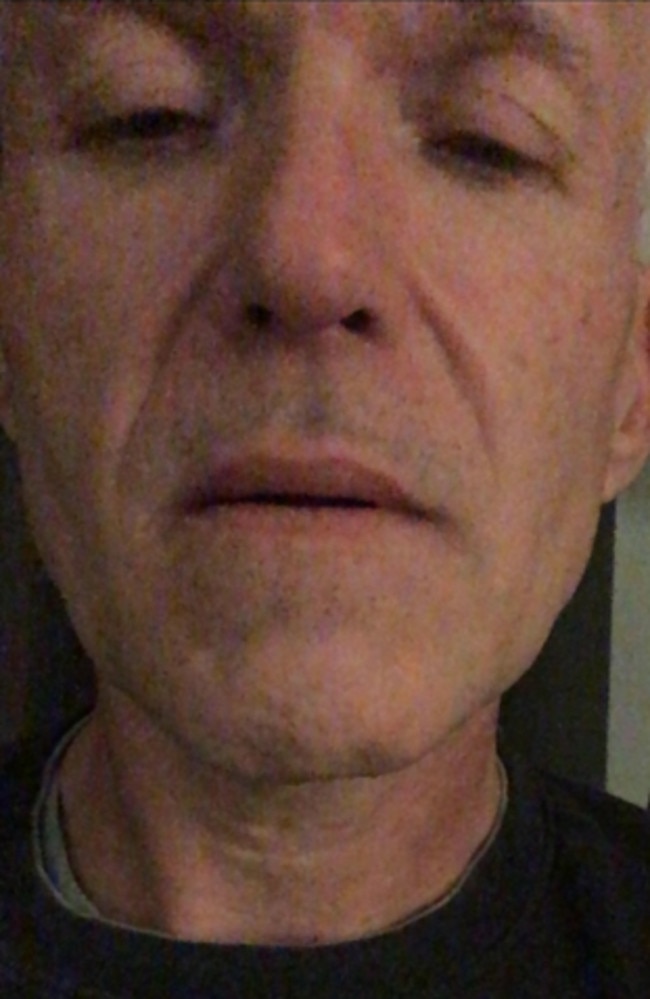

Mr Luxton, a co-school captain who was “thick as thieves” with Ms Palaszczuk at Jamboree Heights State School before a lucrative career with Scotia Bank in Canada, was trying to get home from Auckland to his family in Brisbane to recuperate from depression exacerbated by Covid lockdowns when the tragic fiasco occurred in July, 2020.

Three days into his two-week hotel quarantine at the Brisbane Marriott, Mrs Corbett realised her brother’s mental health was rapidly deteriorating due to being isolated.

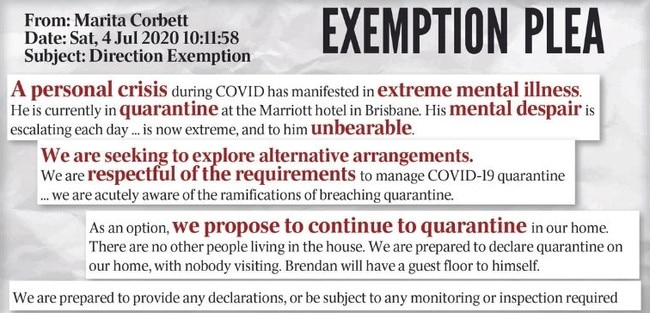

She lodged an official request with Queensland Health on July 4 for him to quarantine at her home, warning his “mental despair is escalating each day and is now extreme, and to him, unbearable”.

She outlined a Covid-safe plan, which would provide her brother a separate guest floor of her large home, and guaranteed her husband would move out and she would take leave from work to quarantine herself, so there would be only two people in the house.

Queensland Health – which granted celebrity Dannii Minogue a home quarantine exemption the following week – has admitted it failed to even bother responding to the family’s application.

Mrs Corbett received an automated reply acknowledging her application, then no further communication until after Brendan, by then in a “dissociative” state, killed himself 24 hours after release from quarantine.

During the escalating crisis while he was in the hotel, the siblings made at least seven separate phone calls to Queensland Health – spending hours on the line – begging for help as their brother’s mental state worsened.

“It is staggering to me that despite outlining Brendan’s mental health history, and submitting a detailed Covid-safe plan, our application was just thrown on the pile,” Mrs Corbett said.

“Dannii Minogue was granted an exemption to quarantine in a Gold Coast mansion, and it’s fine for NRL players to get special treatment, but ordinary Queenslanders get no help.”

Mrs Corbett said when Brendan arrived in Brisbane, on July 2, he was in great spirits.

“He was really looking forward to the resetting of his life and was very positive, but being cooped up in a box quickly put him in grave trouble.”

On July 5 Mrs Corbett contacted Queensland Health to try to escalate the family’s request and was told it was “in the system”.

“Police had done a welfare check on Brendan that afternoon, they had guns as their uniform dictates, but it nearly tipped him over the edge and when I called him he was hysterical with fear,” she said.

By July 12, Brendan was in crisis and needed an urgent intervention.

“I rang Queensland Health again, but the girl in the call centre had no clue what to do,” Mrs Corbett said.

“There was no mention of triage for Brendan or escalation of our case; she just told me to ring Lifeline, but Brendan was far beyond that.”

Derek Luxton, a fitter and turner in Mackay, had also spent hours on the phone to Queensland Health and “got nowhere”.

“Over those two weeks we FaceTimed Brendan constantly and sent care packages, trying to keep him together,” he said.

“But it was a death spiral and we watched our once vivacious big brother disappear before our eyes.

“I am absolutely ropeable that we heard nothing from the Palaszczuk Government until it was too late.”

In hindsight, Mrs Corbett wonders if she had knocked on the door of chief health officer Dr Jeannette Young – who lived a few houses away – would it have made a difference.

“We could have gone to her home but we respected her privacy and decided to trust the process,” she said.

In her exemption application, Mrs Corbett, a senior partner in an accounting firm, said Brendan had been treated for anxiety and depression for about 18 years but the impact of Covid had “manifested in extreme mental illness”, including suicidal ideations.

“As a last resort, he has left Auckland permanently to return home to Brisbane where he can be supported by my family through treatment,” she wrote.

Brendan was released from hotel quarantine on July 16 and went to stay at Mrs Corbett’s house.

Their mother Liz Luxton, then 76, had also moved in to help care for her eldest child, who by this stage was not speaking and “disassociated”.

On July 17, a few hours after Brendan finished breakfast, Mrs Corbett went looking for him. She found him dead in his room.

On July 20, the family was contacted by coronial counsellor Liz Wapples, who requested they document the circumstances of Brendan’s death.

Mrs Corbett wrote a detailed account that day, and on July 22 forwarded a copy to then health minister Steven Miles.

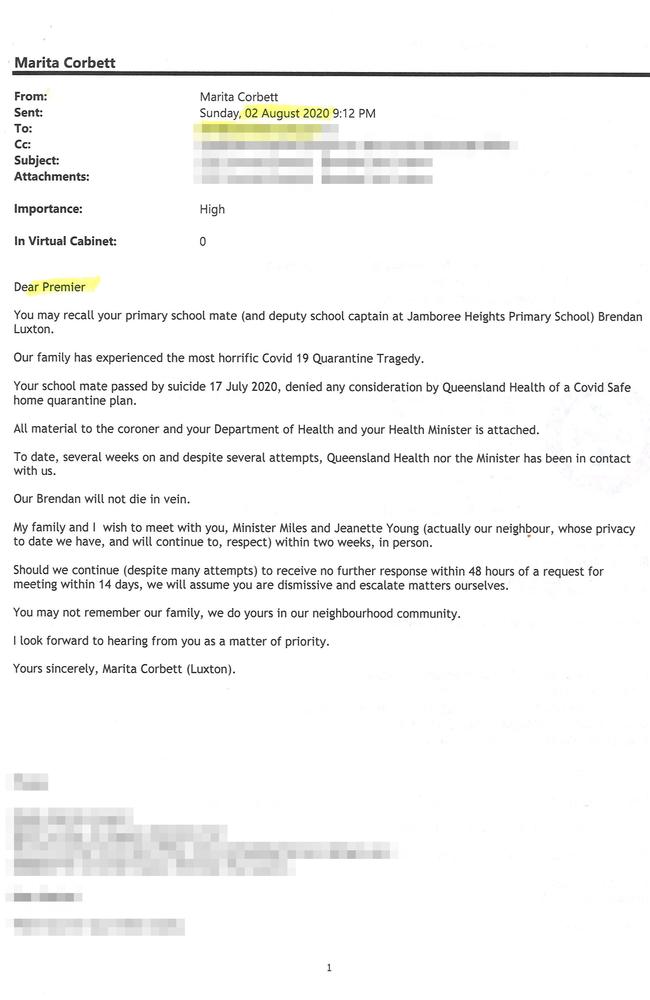

On August 2, still with no satisfactory response from Queensland Health, Mrs Corbett emailed the Premier.

This was the first time the family mentioned that Ms Palaszczuk and Brendan were childhood friends.

Mrs Corbett requested a face-to-face meeting with Ms Palaszczuk, Dr Miles and Dr Young.

“You may not remember our family; we do yours in our neighbourhood community,” she wrote.

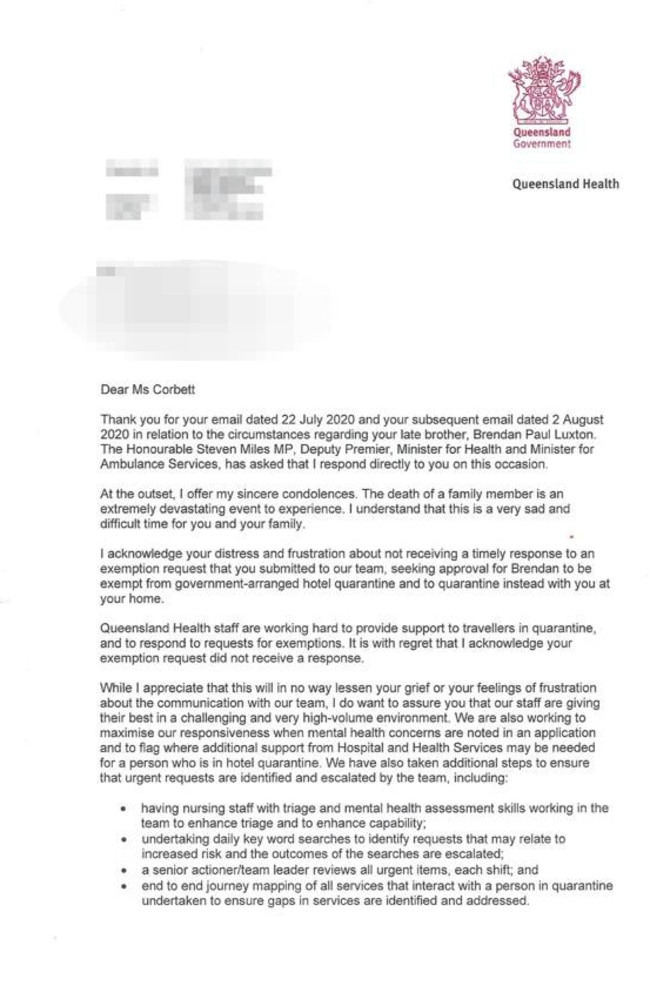

On August 4, Mrs Corbett received a letter from a bureaucrat in the office of the director-general at Queensland Health, acknowledging the family’s “exemption request did not receive a response”.

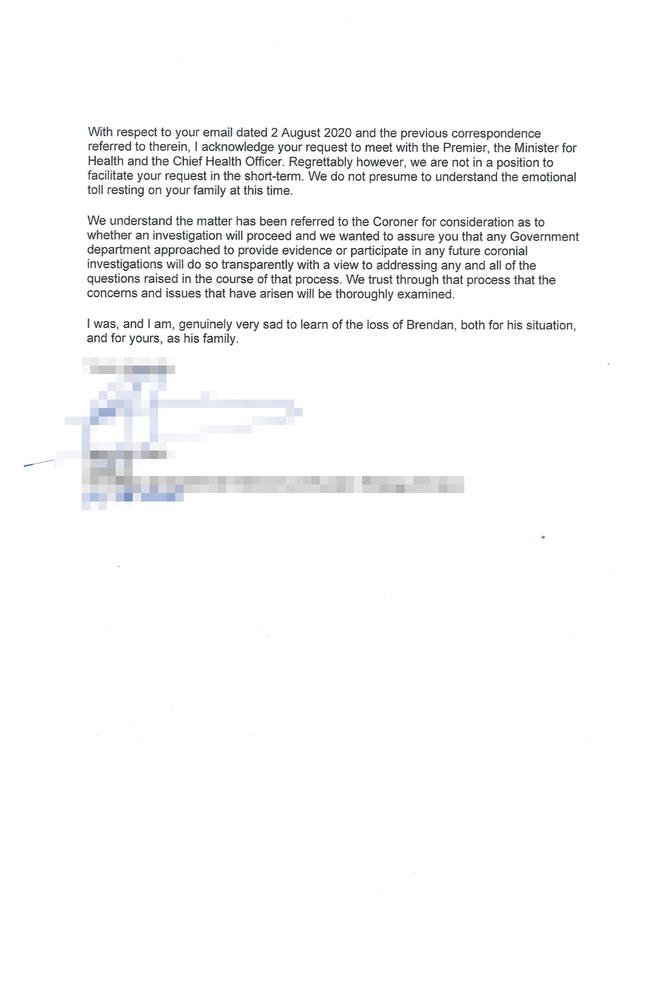

The bureaucrat said they were “not in a position to facilitate” her request to meet the Premier, Health Minister and CHO.

The letter also said: “While I appreciate this will in no way lessen your grief or feelings of frustration about the communication within our team, I do want to assure you that our staff are giving their best.

“We have also taken additional steps to ensure urgent requests are identified and escalated”, including “having nursing staff with triage and mental health assessment skills working to enhance triage” and “undertaking daily keyword searches” to identify increased risk.

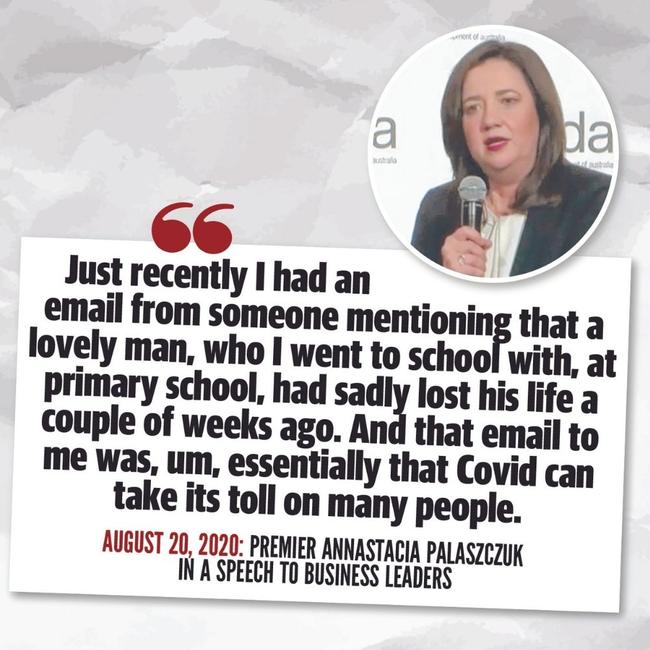

A little over two weeks later, on August 20, Ms Palaszczuk told a business lunch she had received an email mentioning that a “lovely man” she went to primary school with had “sadly lost his life a couple of weeks ago”, and it showed that “Covid can take its toll on many people”, including “the most bright and active person”.

Ms Palaszczuk announced a $46.5 million government spend on mental health services “so Queenslanders can make it through this”.

Derek Luxton, 48, said he was “disgusted” with the Premier.

“What happened to my big brother and to our family was horrific, but to callously use him to give her so-called mental health plan a personal connection is the lowest of the low,” he said.

“When we submitted the request for home quarantine, we weren’t expecting any special favours; we never mentioned Brendan’s friendship with Stacia.

“We followed Queensland Health protocol but were ignored. We never even got a response, and we strongly believe if Brendan had been released from the four walls of that small hotel room, he’d be alive today.”

On August 21 – the day after the Premier’s speech – a bureaucrat responded on the Premier’s behalf, offering “deepest condolences”.

The letter said the Queensland Government was “working hard to ensure appropriate mental health and psychosocial supports are provided for people in hotel quarantine”.

Mrs Corbett said her brother’s death was proof the government needed to work harder.

“Has Annastacia learnt nothing from the fact she was aware of a tragedy, of a person she knew well – a highly intelligent, switched on person? The processes the Premier has set up through Queensland Health have not worked from day one, and 14 months on, they still don’t work,” she said.

“At some point you’d think she’d have said, ‘hang on, something’s not working here, I need to fix this, I’m the Premier’.”

When questions were put to the Premier about Brendan Luxton’s case, a spokesman said Ms Palaszczuk “remembers Brendan from primary school and remains saddened by his passing”.

He said a reply to the email from Marita Corbett “expressed the Premier’s condolences and ways the family could access support and information together with contact details for senior departmental staff”.

While Mrs Corbett said no coronial inquest was underway, the spokesman said “it was explained that because a coronial inquest was underway, it was inappropriate for the Premier

to meet with Brendan’s sister as she’d asked.”

Read related topics:Annastacia Palaszczuk