Six reasons why John Sosso’s appointment should send political alarm bells ringing

The Fitzgerald Inquiry still sets the gold standard for any integrity test, so when a government starts fiddling with electoral boundaries, history demands that we pay attention. WATCH THE VIDEO

QLD Politics

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD Politics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A senior bureaucrat with long-running ties to the LNP government has just been appointed to one of the most politically sensitive jobs in the state — redrawing Queensland’s electoral boundaries.

But if your political alarm bells aren’t ringing, it might be because you weren’t around for the 1987-1989 Fitzgerald Inquiry.

Queenslanders aged 18 to 34 comprised approximately 25 per cent to 30 per cent of the voting population, so it’s crucial to know that this inquiry remains the benchmark for any integrity pub test of any government decision today – especially when those decisions are directly tied to the very process of choosing what seats - and where they are - make up the Queensland parliament.

It comes after the controversial appointment of Jarrod Bleijie’s right-hand man, John Sosso, to the independent Queensland Redistribution Commission.

The state government ignored fears from corruption buster Tony Fitzgerald to appoint Mr Sosso last week, sparking major backlash from the Labor opposition.

Here are six reasons why the Fitzgerald Inquiry still sets the gold standard for any integrity test — and why, when a government starts fiddling with electoral boundaries, history demands that we pay attention.

1. It exposed just how cooked Queensland politics was

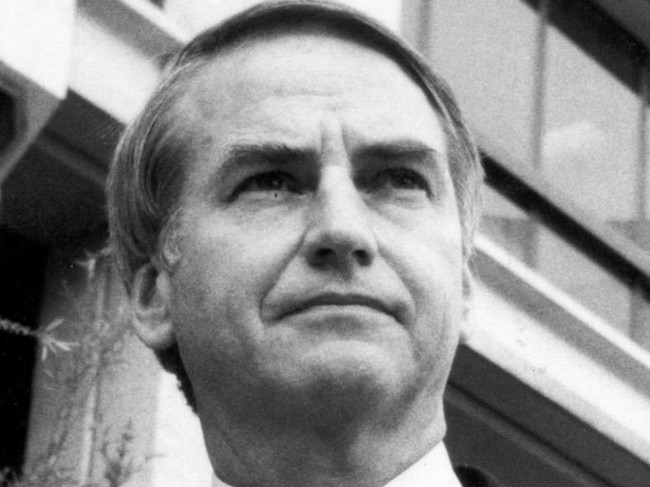

Commissioner Tony Fitzgerald ignited a reckoning.

He was initially tasked with investigating allegations of police corruption — specifically involving illegal gambling and vice operations in Queensland.

Bribes, bagmen, rigged police investigations, illegal casinos protected by lawmen — it all came out.

The inquiry was triggered in 1987 following explosive reporting by Courier-Mail journalist Phil Dickie, which detailed a network of protected brothels and illegal casinos operating with the knowledge, and often participation, of senior police.

At first, Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s government tried to downplay the scandal.

But when a televised Four Corners investigation by Chris Masters aired shortly after, public pressure forced then-Police Minister Bill Gunn to announce a commission of inquiry.

Fitzgerald’s original brief was narrow: look into allegations of police misconduct.

But once the inquiry began, the evidence piled up fast — and the scope exploded.

It soon uncovered systemic corruption in the Queensland Police Service, bribery of politicians and public officials, organised crime and a political system that had protected and enabled this corruption for decades.

2. It killed off gerrymandering

The National Party had turned the state into a political fortress, backed by a police force that had become a criminal enterprise.

Before Fitzgerald, rural seats were deliberately made smaller than city ones — stacking the deck in favour of the Nationals.

Dubbed the “Bjelkemander” after former Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who clung to power despite plunging popular support, the system was designed to give rural and regional areas more political influence than urban voters, despite rural seats having far fewer voters than city seats.

For example a Brisbane seat might have 30,000 voters and a rural seat 10,000 but both had one elected MP.

That meant one vote in the bush could carry two to three times more weight than a vote in Brisbane or the Gold Coast.

On top of this, the Nationals packed Labor voters into the metropolitan zone and deliberately under-allocated seats there while rural areas where the Nationals had the most support got more seats per capita.

The result? Bjelke-Petersen could form government with less than 40 per cent of the statewide vote, winning government via majority seats but without the actual votes. It kept him in power nearly 20 years.

Fitzgerald’s recommendations led to more balanced electorates and the end of vote-rigging by design.

3. It burned the rot to the ground

This wasn’t a symbolic inquiry. People went to jail.

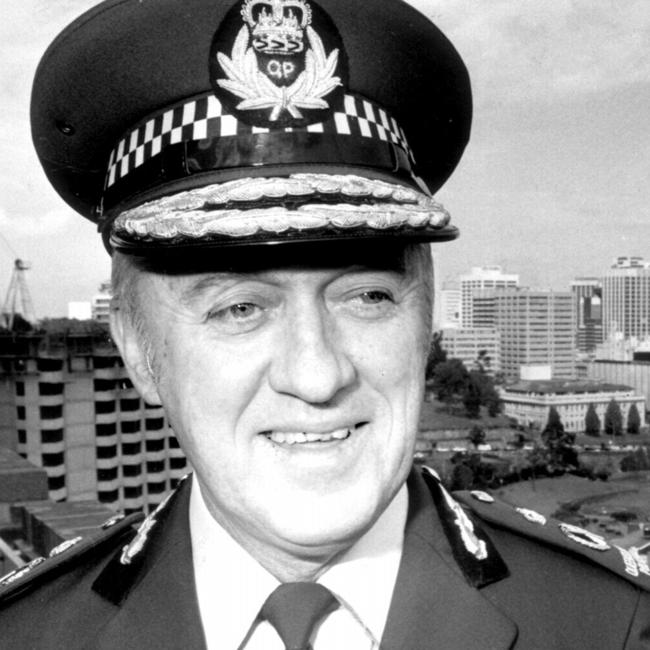

Police Commissioner Terry Lewis — once knighted — was stripped of his title and jailed for 14 years.

He had received hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes and ran a protection racket that helped shield illegal gambling and prostitution in the state.

Four former state ministers — including powerful figures in the National Party — were also convicted and jailed for corruption, perjury, and misusing their office for personal gain.

Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen himself was forced out of office before the Inquiry even concluded.

He was later charged with perjury, but his trial collapsed after a mistrial — later revealed to have been caused by a pro-National Party plant on the jury.

4. It overhauled how judges and public servants are appointed

Speaking of interfering with the judicial system, before the Inquiry, judges could be hand-picked based on political loyalties.

Bureaucrats were often chosen for their party ties, not their qualifications.

Fitzgerald changed that — establishing the principle that senior appointments should be merit-based and transparent.

So when someone like John Sosso — who previously served as Director-General under multiple LNP governments — is tapped to help reshape Queensland’s electoral map, eyebrows should be raised.

Not because he’s incompetent — far from it — because, as Labor has argued, perception of bias is enough to damage public trust.

5. It built the watchdogs we rely on today

The CCC (Crime and Corruption Commission), the Electoral Commission, judicial appointment reforms — they’re all Fitzgerald’s legacy.

They were designed to make sure no government, regardless of party, could stack the deck again.

The overhaul of the Electoral Commission of Queensland (ECQ) to remove political influence from how elections are run is about to be put to the test again today.

The independent body tasked with drawing electoral boundaries must do so based on fairness and population data, not party loyalty or backroom deals.

But these guardrails only work if they’re respected.

The Fitzgerald Inquiry assumed a level of good faith: that future governments, regardless of party, wouldn’t try to claw back control by stacking boards, cherry picking watchdogs, or quietly undermining the very bodies meant to scrutinise them.

6. Because the cracks are showing again

Despite the current outcry over Mr Sosso’s appointment, one cannot ignore the erosion of transparency when Labor was at the helm in recent years.

Delayed RTI (Right to Information) requests, controversial appointments, cabinet decisions made behind closed doors.

Multiple integrity scandals hit the Palaszczuk Labor Government and were laid bare in the Coaldrake review commissioned by Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk herself.

The state’s Integrity Commissioner, Dr Nikola Stepanov, resigned, alleging interference and claiming her office had been raided by the Public Service Commission, with files accessed without her knowledge.

Queensland’s former State Archivist, Mike Summerell, publicly said he was pressured to alter reports and experienced a culture where transparency was discouraged.

The method of the Crime and Corruption Commission had also come under fire after the controversial collapse of a long-running prosecution of Logan City councillors, leading to questions about how political and legal power was being used — or abused.

Tony Fitzgerald and retired judge Alan Wilson were tapped to lead that review.

But even before he got to work, Fitzgerald issued a sharp public statement warning that Queensland was “clearly in a serious integrity crisis” and that there were “disturbing signs of regression to the dark days before the Fitzgerald Inquiry.”

This 2022 inquiry found the CCC had exceeded its powers, and the government was later criticised for its handling of the fallout.

And when Professor Peter Coaldrake released his independent review of public sector integrity in June 2022, Queensland learned their highly paid public servants were being pressured to align with ministers’ preferences, scared to speak up about corruption and were being promoted based on their connections.

Boards were stacked with Labor-linked appointees, external consultants were often hired to provide the advice government wanted, bypassing internal checks and contracts and cabinet decisions were kept hidden from public view.

Fast forward to today, nearly 36 years after his first Inquiry and only a couple since his he last waved a red flag, Fitzgerald has heeded another warning to the Crisafulli LNP Government.

Appointing Jarrod Bleijie’s Director-General John Sosso to the QRC could signal a regression to the “notorious Queensland gerrymander” era.

“I sincerely hope that isn’t so. Biased electoral boundaries fundamentally conflict with democracy,” Mr Fitzgerald said.

That warning was ignored this week, with the Governor-General Jeannette Young officially signing off on his appointment, as recommended by Attorney-General Deb Frecklington.

Let us hope we do not let the father of integrity down, again.