Meet 10 everyday SEQ medical masterminds changing lives across the globe

Be it restoring eyesight, developing vital vaccines, or diagnosing debilitating diseases early, these 10 researchers are the brains dedicated to solving the world’s most complex mysteries.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They’re the brilliant minds working behind the scenes to help improve lives across the world.

Passionate about their research, these Queensland-based scientists and researchers work around the clock to transform their dreams of helping others into a reality.

Whether it is to restore eyesight, develop vital vaccines, or find a way to diagnose debilitating diseases early, these medical researchers from across the Sunshine State have dedicated their lives to their craft and won’t stop until they solve some of the world’s biggest medical mysteries.

Dr Natasha Reid

University of Queensland

While working in an out-of-home care service organisation, the University of Queensland’s Dr Natasha Reid frequently encountered children labelled with suspected foetal alcohol syndrome.

“I had not learnt anything about it during my undergraduate psychology training. I started asking questions and was told that this was a condition that couldn’t be diagnosed, that there was nothing that could be done,” Dr Reid said.

“This didn’t sit well with me, I thought … there must be ways to identify this condition and things we can do to help.”

Now Dr Reid has conducted the world-first review into the relationships between prenatal alcohol exposure and potential diagnostic features of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD).

The diagnostic features can include distinctive facial features and a wide range of neurodevelopmental areas that can be impacted by prenatal alcohol exposure.

The next phase is the dissemination and implementation of national clinical practice guidelines for the assessment and diagnosis of FASD.

“Our hope is that this will lead to earlier and more accurate diagnoses, enabling timely and effective support for children and families affected by FASD,” Dr Reid said.

Professor Paige Little

Queensland University of Technology

Helping children with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis has always been Professor Paige Little’s passion.

A biomechanical engineer of 18 years, the Queensland University of Technology professor has been able to aid young children with spinal deformities in several ways.

Teaming up with mattress company, Sealy Australia, Prof Little developed custom mattress supports for children to lie on when undergoing significant surgeries.

“For a subset of children undergoing significant spinal surgery, they can’t lie safely on their back for the whole length of the operation as it might be a risk to their heart, chest, or breathing,” she explained.

For children too young for corrective surgery, a bespoke brace to support their spine is the best option.

Working with the spinal orthopaedics team at the Queensland Children’s Hospital, Prof Little provides braces that allow young children to sit up without discomfort.

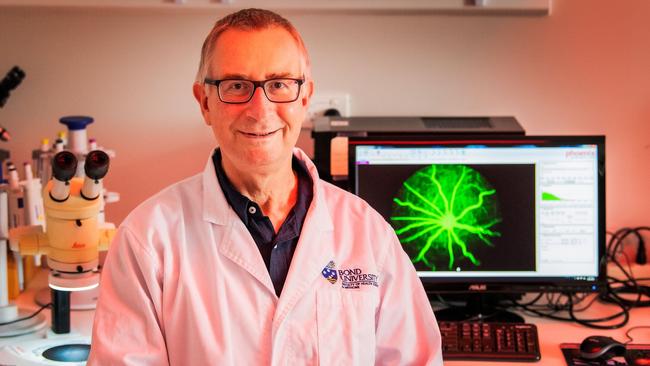

Dr Jason Limnios and Professor Nigel Barnett

Bond University

For Dr Jason Limnios and Professor Nigel Barnett, restoring retina cells to help cure Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is the mission.

The team at Bond University’s Clem Jones Centre for Regenerative Medicine are working to develop and test a delivery system of stem cell-derived retinal cells, to form a uniform layer of retinal cells that function like cells in the healthy eye.

The replacement of retinal cells would help improve and reverse AMD, which causes the loss of the centre field of vision.

“At the moment we can recreate quite a few different cell types in the retina, particularly the ones that die in AMD,” Prof Barnett said.

“When cells in your central nervous system, like your brain or retina, die they don’t replace themselves – once they’re dead, they’re dead.

“The only way to get the function back that’s lost when those nerve cells have died is to make new ones.”

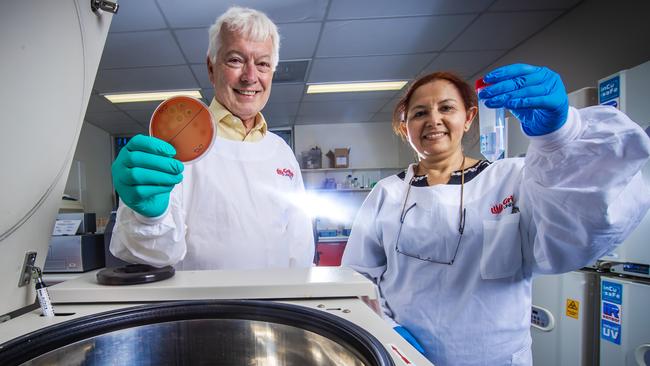

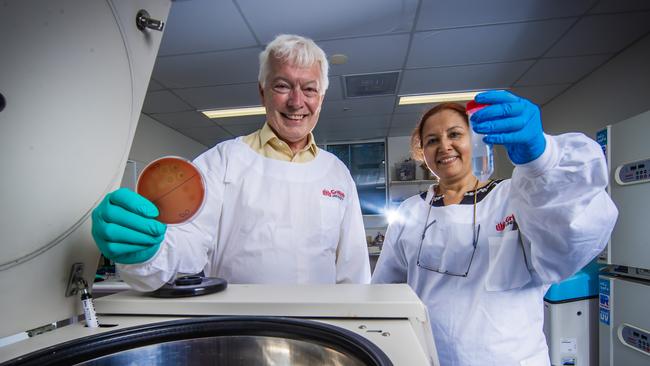

Professor Michael Good and Professor Manisha Pandey

Griffith University

At Griffith University, professors Michael Good and Manisha Pandey are on the verge of developing a vaccine for Group A Streptococcus or Strep A.

Strep A is responsible for rheumatic heart disease as well as many cases of deadly invasive disease and toxic shock.

It is estimated around 500,000 people die each year as a result of Strep A infection.

A human clinical trial, which started in November, is currently underway at the University of Alberta, Canada where volunteers are receiving the vaccine to test for safety and immunogenicity or whether the vaccine would provoke an immune response.

“The vaccine, developed by Griffith University, is designed around key immune determinants, defined by the research team, which represent the organism’s Achilles heel,” Prof Good said.

“It has been a long journey with many ups and downs, there have been many challenges but we can see the light at the end of the tunnel now,” Prof Pandey added.

Professor Rajiv Khanna

QIMR Berghofer

A team of Queensland researchers have dedicated themselves to saving the lives of critically ill Australians with a powerful immunotherapy targeting out-of-control viral infections.

Cellular immunotherapy has been used as an effective method to treat cancer, auto-immune diseases, and infectious diseases.

Now, the therapy has been found to tackle uncontrolled viral infections stemming from a common virus, such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), BK polyoma virus, John Cunningham virus, and adenovirus.

QIMR Berghofer professor Rajiv Khanna and his team have been developing the therapy for more than 15 years, and have now saved the lives of dozens of patients across the nation.

Supplied through the Therapeutic Goods Administration’s Special Access Scheme, patients can access unapproved therapeutic goods as a last resort for treatment.

“In the longer term, Australia should have a centralised cell repository that can be available to the patients in a more regulated way – that would be wonderful,” he said.

Professor Perry Bartlett and Dr Daniel Blackmore

Queensland Brain Institute

High-intensity interval exercise has been found to improve brain function in older adults for up to five years thanks to a Queensland Brain Institute study.

Ageing is one of the biggest risks for dementia, a condition that affects almost half a million

Australians.

Emeritus Professor Perry Bartlett and Dr Daniel Blackmore led a longitudinal study in which a cohort of 200 volunteers aged 65 to 85 did physical exercise three times a week and had brain scans over six months.

Emeritus Professor Bartlett said it is the first controlled study of its kind to show exercise can boost cognition in healthy older adults not just delay cognitive decline.

“Six months of high-intensity interval training is enough to flick the switch,” Emeritus Professor Bartlett said.

“If we can change the trajectory of ageing and keep people cognitively healthier for longer with a simple intervention like exercise, we can potentially save our community from the enormous personal, economic and social costs associated with dementia.”

Dr Kylie Alexander

Mater Research

Queensland researchers have cracked the code to neurogenic heterotopic ossification, identifying the cause and measures to prevent the debilitating condition.

NHO causes bone to form in soft tissue, like muscle near the hips and knees.

The condition typically develops after a spinal cord or brain injury, with 20 per cent of patients who suffer spinal injuries affected by NHO.

Now after ten years of focused study the team, led by Mater Research’s Dr Kylie Alexander, have discovered the condition could be treated with drugs that block cortisol receptors after stress hormone was identified as a trigger for NHO.

“It is a horrible condition to be afflicted with following a serious injury, with long and delicate surgeries to cut away the bone growth the only available treatment. Sometimes the condition recurs after surgery,” Dr Alexander said.

The next stage for Dr Alexander is initiating clinical trials of the treatment at hospitals across Australia, Europe and the United States in the next few years.