Global Fishing Watch finds 20 dark vessels per week in Great Barrier Reef

A global study of satellite radar images revealed there could be as many as 20 ‘dark vessels’ in the Great Barrier Reef every week, but local fishos and authorities claim it’s all above board. DETAILS

Mackay

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mackay. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Groundbreaking research crunching the numbers on how many ‘dark vessels’ use the Great Barrier Reef every week has raised fears of illegal fishing — but there’s no certainty on how many are just innocent boaties.

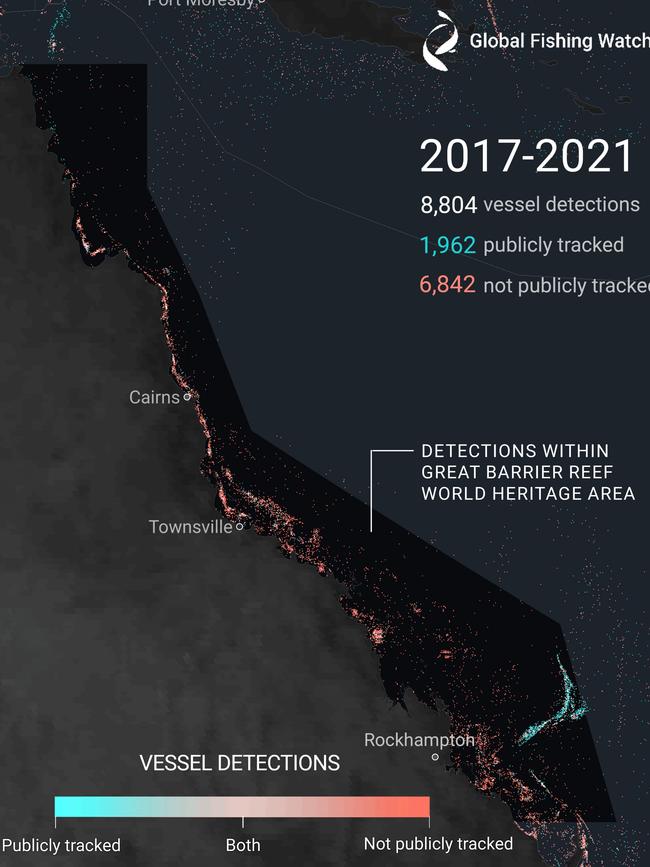

Global Fishing Watch — a non-profit ocean watchdog — recently released a study estimating 75 per cent of industrial fishing occurs without public monitoring systems.

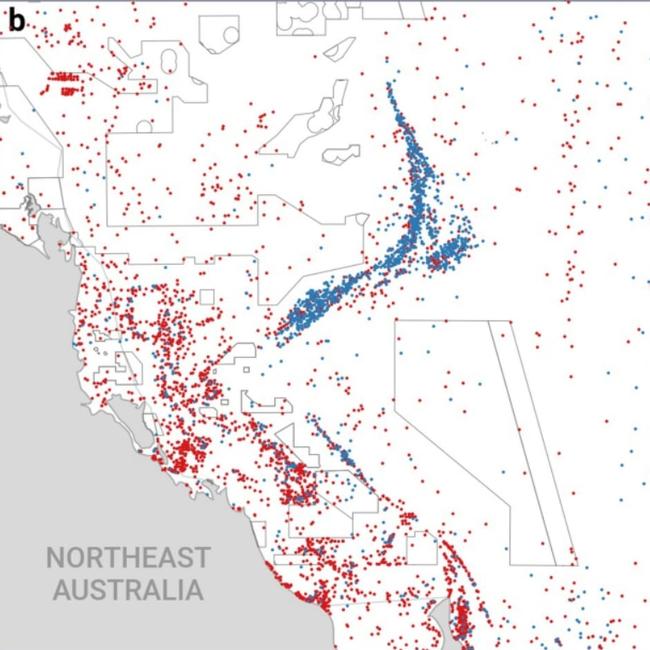

Using AI and two million gigabytes of satellite-based radar images matched to automatic identification systems (AIS), research published in Nature also stated there may be 20 so-called ‘dark vessels’ entering the Great Barrier Reef each week.

Yet local commercial fishers, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, and the researchers themselves say it is unlikely these vessels are illegally fishing in protected zones.

Mackay Reef Fish Supplies owner David Caracciolo said he would be “very surprised” if dark vessels were getting away with poaching, and that the numbers were more likely recreational boats and local anglers linked to the reef’s booming tourism industry.

“We’ve not had any reports of illegal fishing on the reef,” Mr Caracciolo

“If there are illegal fishing vessels whether from Australia or overseas, coastal surveillance is not doing their job very well.

“Even commercial tourism boats, I don’t think they have to have GPS on under regulations.

“They can go and do what they want as long as they don’t fish the green (“no-take”) areas.”

Mr Caracciolo said illegal fishers had not been a hot topic since the 1970s, when Taiwanese clam poachers harried Australian waters.

The GBR Marine Park Authority said there were “currently no instances of illegal foreign fishing occurring within unregistered ‘dark vessels’”.

The Authority said commercial fishers were generally not required to fit AIS but secure satellite-based vessel tracking, and the resulting data not made public to protect their privacy.

Transparency in how people use the world’s biggest shared natural resource is important for everyone, but until now the ocean’s sheer size has limited broadscale tracking.

Study co-authors Fernando Paolo and David Kroodsma agreed dark vessels were not necessarily illegal, but in response to further questions said their 20 per week estimate was “conservative”.

“All we can say is that we detected vessel occurrences within the GBR area that were not trackable by AIS and our model suggests those were likely fishing boats,” they said.

“It is possible that many of those ‘dark vessels’ were recreational fishing or tourism-related (but) they were ‘dark vessels’ nonetheless, meaning they were not publicly trackable.”

The co-authors said their main objective is to increase transparency on vessel activity in the ocean, pointing to countries like Indonesia and Peru where vessel monitoring data is made public.

“We believe that transparency - making ocean information available and accessible to everyone it affects - is a vital tool to support sustainable fisheries, maintain thriving coastal communities, protect crew on-board vessels, and encourage effective governance,” they said.

“If the local fishers are concerned about the perception of fishing within the park, they could consider sharing vessel tracking data, similar to what a number of countries have done.

“And that is the key message of the figure and the paper.”