AI can predict methane levels in coal mines, study finds

Long gone are the days of canaries in coal mines, but new research has found artificial intelligence could issue methane warnings before an explosion occurs. See how.

Long gone are the days of canaries in the coal mines, but new work by Aussie researchers has found artificial intelligence could monitor “hidden patterns” and issue warnings before a methane-related incident underground.

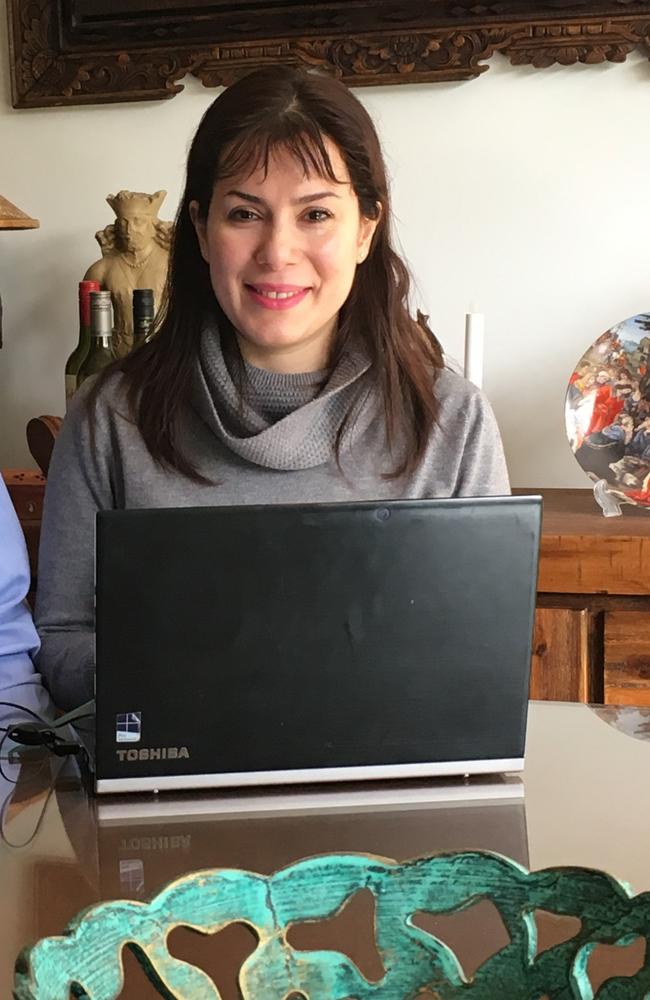

Charles Darwin University adjunct Associate Professor Niusha Shafiabady conducted the testing, and found four AI methods were particularly good at “short-term forecasting” methane levels – aka, predicting what’ll happen in 30 minutes time.

The testing was performed on temperature, gas and wind readings sent to the university by Chinese Shanxi Coking Coal Group.

Data from one of Shanxi’s underground mines was used to ‘train’ 10 AI methods, and the rest of the data was used for testing.

Dr Shafiabady said training the AI to predict methane levels took “under seven seconds”.

“With this study our aim was to have the best accuracy with the shortest training time,” Dr Shafiabady said.

“The training only took a few seconds. Our next study will be looking at if AI can do long-term forecasting.”

Long-term forecasting will require a few hours training and involves the AI trying to predict the methane levels inside a coal mine a day ahead of time.

Methane is an explosive, poisonous gas that is released as coal seams are mined.

In Queensland, if the methane concentration in an underground mine is greater than 2.5 per cent, it’s considered dangerous, and workers must be withdrawn.

Methane is explosive between 5 and 15 per cent concentration.

Dr Shafiabady said since China mined 46 per cent of the world’s annual coal production, finding ways to increase worker’s safety was important.

“In a real-world setting the AI algorithms cannot be 100 per cent accurate because we cannot train them on all the possible scenarios,” she said.

“But using these findings, we could really produce helpful outcomes for the mining industry to assist in safety… these algorithms can pick up on hidden patterns humans cannot see.”

Dr Shafiabady said four methods stood out as particularly well-suited – the best being ‘Random Forest’, an algorithm that predicted future methane levels with a 0.0008 MSE (means square error) accuracy.

That’s compared to some of the less-suited methods, which were making predictions with 0.6 MSE accuracy.

Dr Shafiabady encouraged any other companies interested in AI solutions to reach out to universities and academics.

“There is a disconnect between industry and academia, so when we find a company that is interested in working with us we do everything possible to help them,” she said.

“In the AI area, a lot of stuff is coming from private start-ups, not researchers. We need to work closer together.”