Libby Trickett’s heartbreaking battle with mental illness

Libby Trickett has revealed her devastating battle with mental illness, detailing in a new memoir how she came apart psychologically during her high-profile swimming career. READ AN EXTRACT NOW

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Olympian Libby Trickett has revealed her devastating battle with mental illness, detailing in a new memoir how she came apart psychologically during her high-profile swimming career.

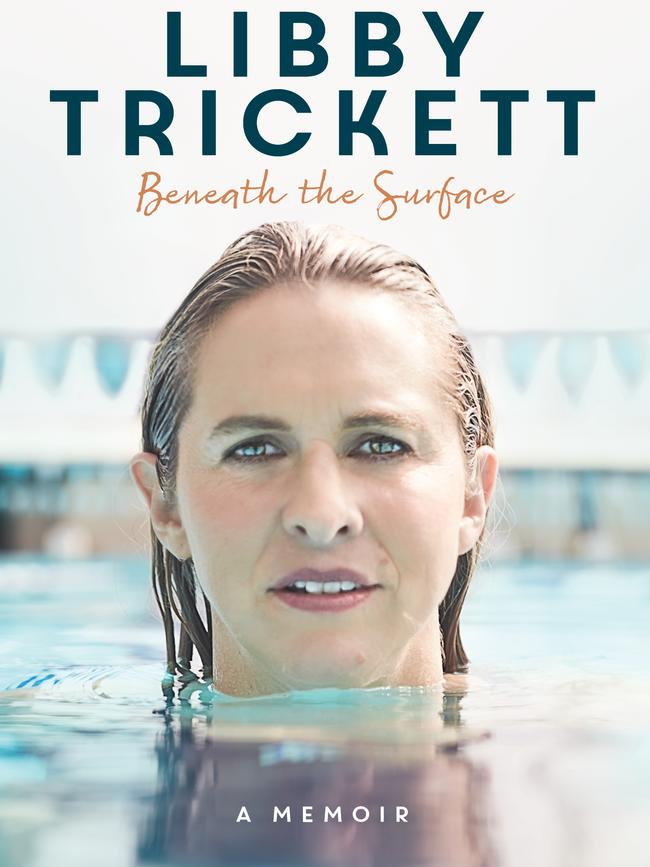

In the memoir, released this Tuesday — Beneath the Surface — Trickett, 34, details how she told herself she was worthless, pathetic and a failure throughout her major swims.

Trickett also details the depth of the postnatal depression she sunk into after the birth of her daughter Poppy, now 4, writing that she had grim thoughts about hurting her daughter before she asked for help.

She says she struggled to recover mentally from a miscarriage at nine weeks, saying she blamed herself for the loss of the baby.

Trickett, who is 32 weeks’ pregnant with the couple’s third child (gender unknown), says she is excited but nervous about the release of the book, and the amount of information she is sharing with the public about her mental health battles. But she says she hopes the book helps others battling mental illness, and encourages people to seek help — like she did — to get through.

Here’s an extract from Beneath the Surface:

There are no waiting times for elite athletes.

When the pain in my wrist doesn’t lift, I go to see one of the leading sports doctors in Brisbane; he sends me for an MRI and refers me to a specialist, and I get in straight away. “You’ve had a catastrophic injury to your wrist,” he says. “It’s

a full tear of the scapholunate, and it could very easily mean the end of your swimming career.”

This is confronting — of course it is. The word ‘catastrophic’ is confronting. But the end of my swimming career? How is that even possible?

I haven’t been in a car accident or had a severe fall. I’m not a footballer — I don’t get smashed around on the field every week. I was doing weights at the gym one day and felt a twang in my wrist. And now we’re talking about the end?

In 20 years of competitive swimming, including three Olympic Games, I have never had a single injury. OK, so I’m injured now, but that doesn’t mean it’s over. I feel like I only just found my groove again. I came out of retirement, I swam at the London Games. I’ve only just rediscovered my passion for swimming, that real love of the water. So it can’t be over now — I won’t let it be. No worries, I think to myself. I’ll come back from this. But the word ‘catastrophic’ keeps bouncing around in my head.

I want to go to my fourth Olympics so badly

I can taste it. After a while, your career is not about any single gold medal, it’s about longevity. It’s about how long you can perform at that level. The pack starts to fall away, and you find yourself in a rarer and rarer crowd, the elite of the elite.

And you get a rush from chasing that kind of distinction. I’m swimming for my legacy. This goal has become weird and obscure, but it’s still a goal, something out in front of me that I can strive for, that drives me forward. It’s something that I can channel all of my competitive spirit into, that restless energy that has always been inside me. Three Olympics is impressive, but four is legendary. If I swim at four Olympic Games, history will remember me. I don’t mean to sound egotistical — I just want people to think of me fondly, the way I think about the great swimmers who came before me.

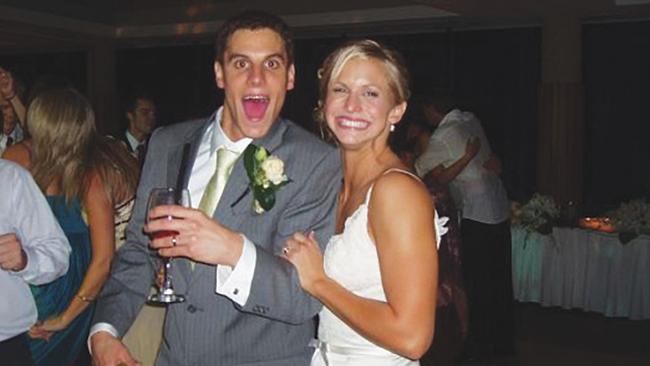

The surgery is a success, but it’s incredibly painful. I’ve never had any trouble sleeping before but I find that if I roll the wrong way in bed or Luke, my husband, knocks me in his sleep, I wake up with my wrist throbbing and break into tears. I’m on strong pain medication but it doesn’t touch the sides, especially in the first few days. The ache is constant. I’m used to pain, to pushing through aching muscles and tiredness in the pool, but this takes me by surprise. The swelling is intense, too.

I feel really off-balance, and training in the pool is out of the question. I try to get back onto the exercise bike, to keep my metabolism up, and I do whatever I can at the gym that isn’t weight-bearing, but it’s not much.

There’s no one moment when everything unravels, just an accumulation of time. It’s a slow winding down, like the air leaking out of a balloon. I start training less and less as time goes by. In the first three months, I am in rehabilitation, healing the wound. In the month or so that follows, I get in the pool and do what little I can. I do my kick sets, try to strengthen my legs, step through the process. I am waiting for the pain in my wrist to ease so that I can step up my training and restart my weight-bearing routine in the gym. But as another month passes, and drifts into two, the pain doesn’t improve — or it doesn’t improve enough. At first I’m patient, but time starts weighing on me. Every month of peak training I lose makes it less likely that I’ll be able to claw my wayback.

But what am I supposed to do, if not this? I have no idea who I am if I’m not a swimmer; my brief flirtation with retirement in 2009 really drove that point home. I have no other skills, no training, no plan B. And I don’t want to do anything else. I wish I could compete forever.

Luke is incredibly supportive. We’ve been through rough patches before, and we both know that communication is key, so he keeps checking in to see how I’m doing. But there’s no pressure, no expectations — he just wants me to do what’s right forme, and I’m incredibly grateful for that. But as the doubt creeps in, I start wondering how we’re going to get by. I’ve been the primary breadwinner throughout our relationship, at first because my career was going well and then because Luke had a new business, and always paid himself last. I’m nervous about how we’ll manage if I’m not swimming. It’s uncharted water.

These thoughts sneak in quietly and begin taking up space in my brain. It’s a gentle creep, month after month, dulling my competitive edge.

I think it’s a form of kindness, really. Like my subconscious mind knows that I can’t deal with what is coming, so it loosens the cap just a little bit and lets the air leak ever so slowly out of my dreams. My body and my heart have accepted that I have to move on, but my mind is slow to catch up. I know that this is a process I have to go through. I think the actual injury was necessary, because I would never have retired of my own volition. And that’s what I have to do: I have to retire. And this time I will not go back.

When I announced my first retirement from swimming in 2009, I just wanted to get it over with, but my manager at the time counselled me to wait until I knew what I was going to do next. “You’re not retiring from something, you’re retiring to something,” he told me. “It’s a much better look.”

I’ve got nothing to retire to this time. I have to tell people that I’m retiring from swimming and I’m drifting off into oblivion, with no further

plans. The path ahead is totally dark — that’s the honest truth.

I’m scheduled to appear on The Project in July 2013, seven months after the operation. It’s time. Part of me wonders if I should even bother making a formal announcement, but it seems to be the done thing and it’s better for my career. I’m thinking about this while sitting in hair and make-up at the Channel 10 studio in Melbourne. What career, seriously? My career is behind me. But the hope is that opportunities will present themselves if people know I’m not busy in the pool. If the reality-TV show actually gets off the ground, I’ll be a media personality, I suppose, but I wish I didn’t have to mention it in the same breath as the end of my Olympic dreams. One of these things means the whole world to me, and the other means nothing at all.

A production assistant comes to collect me, and we walk into the studio where The Project is filming. I marvel once again at how small everything looks in real life — the studio itself, the desk, the audience. But the lights are startlingly bright, and I can feel the adrenaline building as I take my seat and say hello to the hosts, who are shuffling their papers and getting ready to come back from the commercial break. Then the red light on the camera flicks on and everyone is smiling at me; all kind people. And I smile back and tell them that my swimming career is over.

No one is what they seem on the surface. Life is long and complicated, full of ups and downs, and it’s almost impossible to understand what someone else is going through at any given time. Things don’t always feel as great as they look, and sometimes they don’t look as great as they feel.

For me, the most interesting stories we can share about ourselves are the ones that are hidden from sight. For most people, I will only ever be Olympic swimmer Libby Trickett, who had a good run in the 2000s. But I’m not just a swimmer. I am not defined by a few gold medals. I’m a wife, a sister, a media personality, an Instagram addict, a daughter and a mum. I’m a dreamer and a ballroom dancing enthusiast. Sometimes I’m on top of the world and sometimes I’m hopeless, just like everybody else. But people don’t always see both sides of the coin. The dark side doesn’t always make headlines.

My story is as much about struggle and self-doubt as it is about success, and I think it’s the struggle and self-doubt that make me human.

As a swimmer, I learned the importance of focus and setting goals, and the value of hard work — but as I look back on that period of my life, I know that the real lesson I needed to learn was how to be in the moment, emotionally, and appreciate the wins when they came. I needed to learn how to be kind to myself and forgive myself for making mistakes. I needed to learn that not being perfect is perfectly OK.

As a wife, I have learned how important it is to communicate. I was lucky to meet my soulmate at such a young age, but I never want to take that relationship for granted. As much as Luke drives me bonkers sometimes with his ridiculously rational brain, I know that I am blessed to have him on my team.

Meanwhile, my experiences with mental illness have taught me that it’s OK to not be OK. I didn’t recognise that I struggled with mental-health issues during my swimming career, and that made so many things so much harder than they needed to be. Like so many people, I subconsciously resisted the idea that there was something ‘wrong’ with me.

Having anxiety or depression was a weakness, and I wasn’t weak. I just felt really, really awful sometimes, and told myself that was normal. After Poppy was born, when my depression was so intense that it broke through that wall of denial, I learned that real strength comes from reaching out and asking for help when you’re down. You’re not trapped, you’re not alone and there’s nothing wrong with you because you’re struggling. You’re just a human being. We all struggle sometimes. It’s OK. If we can all get better at talking about mental health, I think more people will ask for the help they need.

My recovery from postnatal depression has been slow but steady. You don’t get better overnight, and there is always a risk that depression and anxiety will return. Sometimes

I feel more vulnerable than at other times, and

I still have moments of self-doubt, but watching Poppy grow into a lovely, kind little girl has really steadied my heart.

Every Saturday morning, I take my girls to the pool and watch them splash around, falling in love with the water just like I did when I was their age, and I am so grateful that I have them in my life.

Beneath the Surface is out October 1.

Lifeline: 13 11 14