Joh Bjelke-Petersen left a mixed legacy that 30 years on from his resignation still divides

WHAT Queenslanders think about Joh Bjelke-Petersen is largely defined by geography. Thirty years on from the resignation of the man some dubbed “Saint Joh” and other “Jackboots Bjelke”, Paul Williams reports on the controversial premier’s mixed legacy.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

POLITICAL scientist Rae Wear explained in her biography of Joh Bjelke-Petersen how two radically different views of Queensland’s longest-serving premier can coexist long after his retirement 30 years ago yesterday.

Those who still admire Bjelke-Petersen call him “Saint Joh”, Wear writes, while detractors label him “Jackboots Bjelke”.

What Queenslanders think about Bjelke-Petersen is largely defined by geography, and many in the regions will cite “development”, “standing up to unions”, and Queensland “pride” as the hallmarks of his premiership.

But critics in the southeast will instead describe a corrupted zonal electoral system (initiated by Labor in 1949) that saw Joh retain office despite his party winning as little as 20 per cent support.

They’ll also recount the bags of cash big business “donated” in return for favours, an unemployment rate nudging 10 per cent, and the politicisation of a police service corrupted from the top down.

Opponents will also note Joh’s attacks on the democratic right to protest, the vilification of environmental, indigenous and gay communities (despite his professed Christianity), and the assaults on basic civil liberties. They may also cite the premier’s support of wacky cancer quacks and dodgy hydrogen-powered cars.

Much of southeast Queensland (and Australia) saw the state as a laughing stock – a populist backwater up to its increasingly red neck in corruption.

Critics lamented that we were, at best, Louisiana’s poor cousin, with Joh a rambling Huey Long. At worst, we were a police state closer to Poland than Pennsylvania.

So it is to be expected, after 19 years as premier and 40 as an MP, that Joh’s titanic tenure should divide not only popular opinion but Queensland history itself.

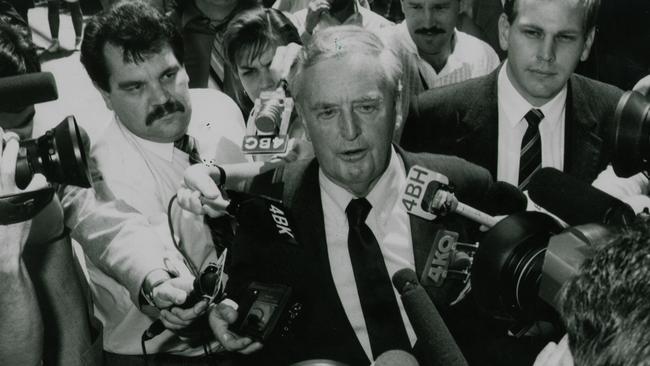

Joh, the icon who towered above Queensland, was humiliatingly forced from office on December 1, 1987, when National Party MPs (governing without the Liberals since 1983) saw him as a political liability after revelations at the Fitzgerald Inquiry into official corruption – which lasted two years, saw four ministers and a police commissioner jailed (and Joh himself narrowly avoid a perjury conviction) – brought down a government and resulted in a retooling of Queensland’s political rules from the top down.

Those cathartic events ended an era when premiers could be autocrats, where fat donations could be palmed with a nod and a wink, and where “getting things done” was more important than due legal process.

Thirty years on, it’s difficult to conceive of a Queensland without anti-corruption commissions, fair electoral boundaries, and electoral donation laws.

But, despite that neat fold in the page of Queensland’s history, does the ghost of Joh still shape our politics?

University of Queensland political analyst Dr Chris Salisbury believes it does, with a few positive legacies found among the debris.

“There have been two great transformative periods in Queensland,” he says. “Joh’s in the 1970s, when he really opened up the state’s regions to mining, and Peter Beattie’s ‘Smart State’ in the 2000s.”

Griffith University political scientist Dr Tracey Arklay agrees, saying: “Albeit decades after other states, the Art Gallery and QPAC were built, and Expo ’88 happened.

“But most (of Joh’s legacies) can be attributed more to pork barrelling and less to considered public policy. Many more negatives than positives spring to mind.”

To the long list, including unequal votes and diminishing civil liberties, Arklay adds how “our heritage buildings (like the Bellevue Hotel) were lost forever” and how “Fraser Island under Bjelke-Petersen could easily have become an ugly sand mine”.

Salisbury also lists the liabilities, adding that “Queensland education went backwards under Joh”.

Where premiers Frank Nicklin (1957-68) and Jack Pizzey (1968) invested in high schools, Joh echoed Labor’s William Forgan Smith (1932-42) and eschewed formal education.

Now, just a week after a state election in which the divide between Brisbane and the bush has rarely been starker, we can draw clear links between a 1970s Joh and today’s One Nation. It was, after all, a campaign in which the Liberal-National, Katter and One Nation parties scrapped like cats to be seen as the authentic voice of the bush.

But is One Nation Bjelke-Petersen’s genuine successor?

“As much as Hanson would like to think so, that’s inaccurate,” Salisbury says.

“We must remember, Joh encouraged Asian investment, whereas Hanson has railed against foreign ownership.”

Salisbury says Bjelke-Petersen’s free-enterprise rhetoric would also stick in Hanson’s throat.

How, then, will Bjelke-Petersen be remembered in another 30 years? Will his ignominy morph into loveable roguishness?

“I don’t believe Joh’s legacy will be one that future generations will be proud of,” Arklay says.

Salisbury agrees: “It will take more than 30 years for Joh’s legacy to be rehabilitated. Only when everyone who was around in the 1980s dies will that be possible, if at all.”

For Bjelke-Petersen, who died in 2005 after living for 94 years by his own rules, public opinion was of little consequence. His likely comment today would be, “Don’t you worry about that.”

Dr Paul Williams is a senior lecturer at Griffith University’s Schools of Humanities