Bomb hoaxes, bra-burning: The bizarre history of the House of Jenyns factory

We take a look at the colourful history of an iconic Ipswich factory which employed thousands of locals in its 20-year heyday. Strikes, bra burnings and bomb hoaxes, it was never dull.

Community News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Community News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was once one of Ipswich’s biggest employers, but these days few still remember The House of Jenyns/Triumph International bra factory.

With a rich history of strikes, protests, bra burnings, bomb hoaxes and more, it was not just a job to the thousands who worked there until the landmark closed in 1993.

Ipswich has always been a hub of industry, from wool and cotton mills to workshops and meat processing plants, but few became international names like the “bra factory, as most people came to call it.

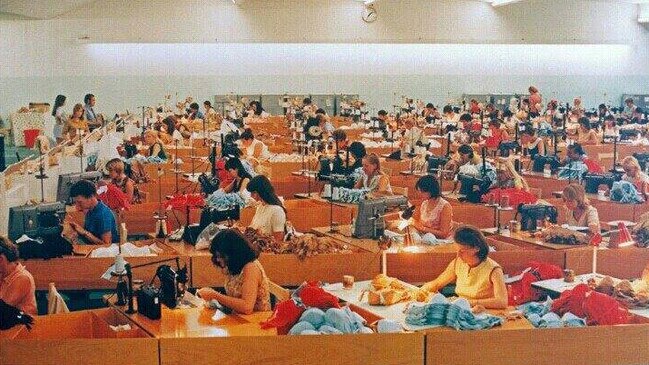

The Ipswich chapter of the story began on September 1, 1970, when the doors opened at the corner of Brisbane and Thorn streets in the CBD.

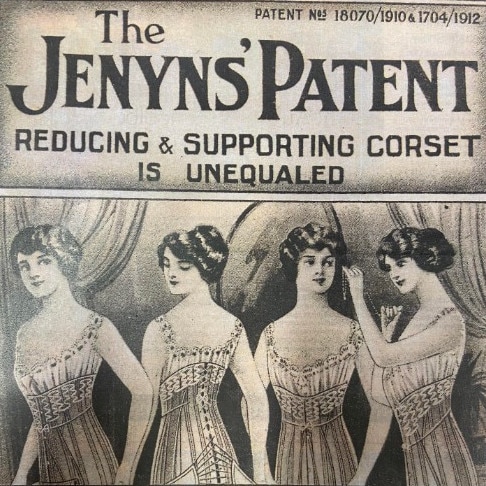

But long before then, in 1898, former nurse Sarah Ann Jenyns founded The House of Jenyns in Brisbane after searching for a pain-free alternative to surgical corsets.

The early factory lacked trained machinists, so the decision was made to open in Ipswich where those workers were readily available.

At the same time, The House of Jenyns merged with Triumph International.

The factory would go on to produce more than 90,000 undergarments each week, from corsets and girdles, to bras, underwear and eventually swimwear.

Eventually, the Ipswich factory and a smaller, second facility in Wulkuraka Industrial Estate became the main production plants for Triumph, a brand which became globally known.

By 1886 there were 400 staff on good wages who pumped much-needed revenue into the local economy.

But the more successful it became, the closer to “catastrophe’’ it came.

Former House of Jenyns employee Jeannie Mair was one of hundreds of staff who was let go after the company moved overseas in an effort to cut costs.

Ms Mair said the decision came out of the blue. She was one of many workers who spent days camped outside the factory in protest.

“A couple of weeks before the strike, management had come downstairs and told us that everything was going well and they had heaps of orders,’’ she said.

“Then the next week they said they were shutting down and moving overseas.

“I think that really stirred the girls up. One minute they said everything was good and the next minute they were closing and we were losing our jobs.”

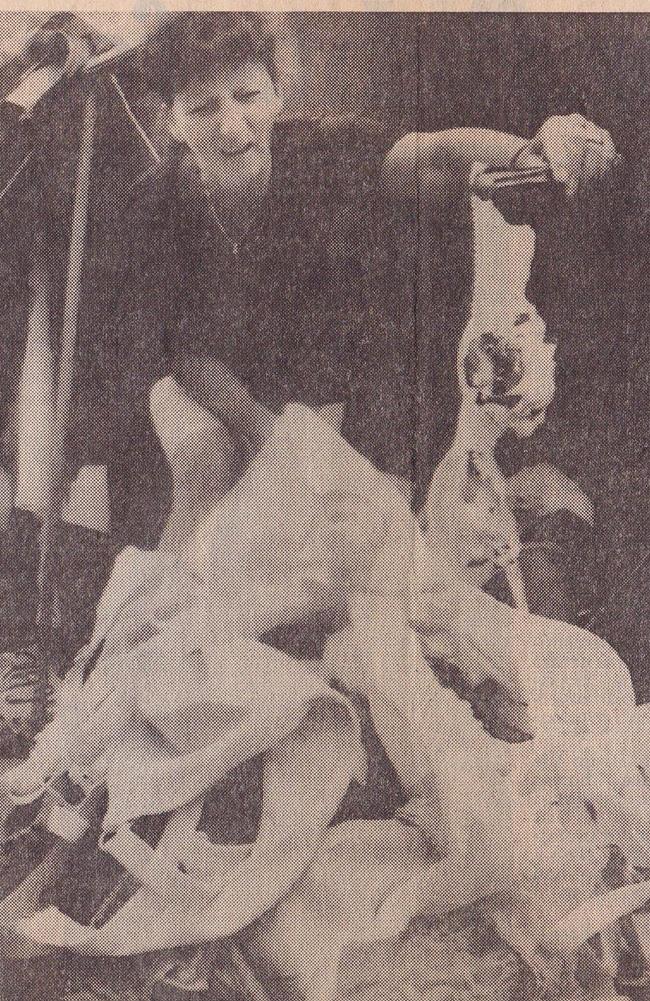

Workers burnt Triumph bras, brandished signs and camped out for more than a week.

“We camped on the footpath — the police would come check on us at night time,’’ she said.

“People driving past were blowing their horns because they supported what we were doing.

“We had a little stove and we used to get food from the bakeries and the fruit and veggie stores would bring us food — it was quite good actually.”

“The girls used to stand at the gate and boo the management and shout out at them.

“I think the management at the Ipswich factory realised how bad it was.”

Ms Mair said then Ipswich City Mayor, David Underwood, told staff Council would back their fight and investigate buying the factory, however Council never followed through.

“A whole bunch of us marched up to the council offices,’’ she said.

“He (the Mayor) said the council would back us but some other councillors didn’t agree, didn’t think it was the right decision.

“Looking back, I don’t know where they would have got the money from anyway.”

Photos published at the time in papers across the country depicted Ms Mair and others burning piles of bras but said that now, at 78, she could not believe she was bold enough to do that — and neither could her grandchildren.

“That photo (below) was printed in a paper in Melbourne and one of my daughter’s friends showed it to her and said ‘hey, your mum’s in the paper,” she said.

“To this day, I’ve never bought a Triumph bra.”

Despite the bitter end to almost 20 years of on-and-off employment for Ms Mair, she still had many fond memories of her time at the factory and made friendships that still thrive today.

She worked at the factory on three occasions from the early 1970s until just before the factory closed in 1993.

Along the way there were some bizarre ups and downs.

“There was one other strike before the one when the announced they were closing and it was because of me,” she revealed.

“It was incredibly hot in the factory and there were no fans or aircon, so we went on strike and eventually they put in these massive fans which was great,” she said.

“We would even get bomb hoaxes sometimes.”

“There were a few times where someone called in to say there was a bomb in the factory and we would all have to evacuate.

“The police came out and checked it out and everything.”

She was one of several former workers who started the ‘I worked at the “House of Jenyns” in Ipswich’ Facebook group.

It has brought together hundreds of former staff and renewed lifelong friendships forged over the tops of sewing machines.

In 2014, Ms Mair was also integral to the organisation of a reunion for former staff.

The factory site is today home to Top Gun Motorcycles which has had an exciting history itself.

Opened in the early 1960s, it met with some controversy and later housed the Ipswich tenpin bowling alley.

The council at the time had just changed the by-laws to allow the bowling alley to open seven days a week, despite bowling still being considered commercial recreation and thus not normally allowed on Sundays.

The site was also home to the Wonderland Ballroom and Teen Scene club, which hosted many dances and events.