Inquest finds heat killed FIFO worker Glenn Newport but a new code of practice will need to differentiate between dehydration and dilutional hyponatremia

“YOU be careful when you go back out there. If it’s too hot, don’t work.” Those were the last words Jenny Newport said as she dropped her FIFO worker son at Brisbane airport. A day later, there was a knock on her door.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

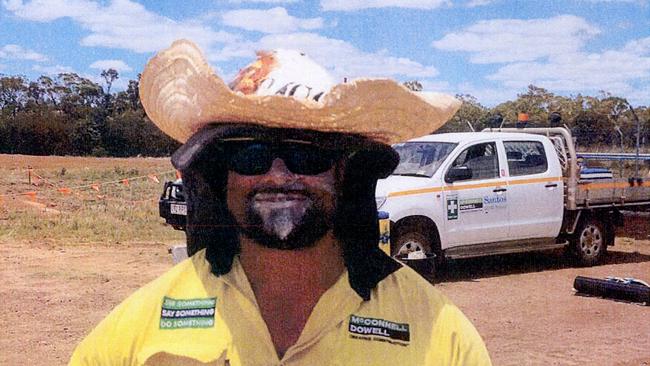

GLENN Richard Newport was a powerfully built man but the stifling summer heat had knocked him around once before on the Roma worksite.

Squatting in the baking red earth in December, 2012, the burly fly-in fly-out worker, who had a deep love of the outdoors, thought his brain was going to “fry” beneath his white hard hat.

When his mother drove him to Brisbane airport on January 12, 2013, after he’d returned home to attend a funeral, the hot weather warnings had been building for days.

“You be careful when you go back out there,” Jenny Newport says she told her 38-year-old son during the 30-minute car trip.

“If it’s too hot, don’t work.”

Just before retiring to bed the next night, she picked up the phone and dialled Glenn’s mobile, anxious to find out how he’d coped in the heat. But there was no answer.

Then, at 2am, came the knock at the door. It was the police.

Jenny’s immediate thought was that their son’s ute had been stolen.

It hadn’t.

There had been an accident, the officers told her and husband Bruce.

Their son, the rover who was just beginning to talk about settling down, had died in an ambulance en route to the hospital, on a stretch of highway 400 kilometres away.

Three years later, Brisbane Coroner John Hutton ruled the muscular worker died from a cardiac arrest, triggered by dilutional hyponatremia – a condition that can befall a person who drinks too much water.

He declared the “principal” cause of Glenn’s death was his “physiological reaction” to working in the extreme heat.

The United Nations has recently warned workers face greater health risks as climate change takes hold and Glenn’s death has stirred debate over how companies manage their workers toiling in higher temperatures.

Glenn was among a workforce of about 250 people on the Santos GLNG upstream project in the Roma gas fields, about 40km northeast of the town, when he died on January 13, 2013.

Such was the ferocity of the heat that morning the company issued a “red alert”.

Although no measurements were taken on the site that day, it’s likely the temperature passed the 40 degree mark, exacerbated by high humidity.

Leading hand Bradley Hall told the inquest that a shade tent was erected at the site and workers were told to wear long sleeves and hats, as well as ensure they had enough water.

It was also, the inquest was told, the practice that if one person needed to have a break, the whole crew would pause for a “smoko”.

Safety officer Paul Hanna said he had visited the crew from time to time that morning, handing out water and ice blocks and urging them to keep hydrated.

In his findings, Hutton reconstructed what then occurred.

Some time after lunch, Glenn, who was doing concreting formwork and following all safety instructions, became unwell.

Despite resting in the shade tent, sharing water and ice with a workmate and sitting in the air-conditioning, his condition didn’t improve.

He was taken to the camp’s clinic, which was manned by paramedics. Concerned about his rate of respiration, the medical staff gave him oral fluids and watermelon to eat.

This is one aspect of the chain of events that Glenn’s mother remains concerned about.

“The hospital was less than 40 minutes away but he wasn’t taken there, as was the standard procedure on other sites,” she said.

After two hours at the clinic, Glenn’s vital signs “stabilised” and he went back to his room, although Hutton says, in his findings, there was some question over whether he did this willingly.

When a friend stopped by his room about 8pm, an incoherent Glenn crashed to the floor after he grabbed a towel rail for support, ripping it free from the wall.

Inside the ambulance, Glenn became “agitated” and the vehicle had to stop so he could urinate.

Hutton’s findings say that, almost straight afterwards, Glenn went into a “rigid extended” position. He was pronounced dead about 11.10pm.

The company McConnell Dowell’s safety processes were raked over at the inquest: why wasn’t there a cut-off temperature at which work should stop? Why wasn’t Glenn taken immediately to hospital?

His family, in their submissions to the coroner, described them as “somewhat inadequate” and broadly written procedures, which were in place only to protect the company from prosecution, rather than to “actually protect their workers”.

The company accepted their heat stress management policies, which were “typical of the industry” at the time were inadequate.

In his findings, Hutton says he was “somewhat startled” to learn there was no industry standard or “best practice” about managing heat on work sites and recommended one be developed urgently.

“The policies which are in place appear to me to have been constructed on the basis of very rudimentary and innocent risk assessments, essentially uninformed by either meteorological science or medicine,” his findings say.

“Had this inquest been able to discover an industry-based best practice, and had McConnell Dowell failed to implement that best practice, then these findings would be much more critical of McConnell Dowell specifically.”

He says the tragedy should be a catalyst for change in the heavy construction industry.

“It seems to me that it was only a matter of time before a heat-related death occurred in this industry.”

In his recommendations, the Coroner says that any code of practice should include a “cut-off temperature” to stop work, provisions for night-time shifts when heat is dangerous and “objective” criteria to determine when ill workers should be evacuated to a hospital.

Hutton went even further, saying a code of practice should be devised for any industry where workers are exposed to extreme heat, including agriculture, mining and the building or landscape industries.

The Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) national secretary Dave Noonan says the likelihood of injury escalates as the temperature rises.

“This is a big problem,” Noonan says and urges workers to ensure they’re covered by a workplace agreement.

“We are aware of situations where workers become sick, have had severe reactions and, in some cases, died after the employers forced them to continue working in excessive heat.

“When temperatures were in excess of 35 degrees, work ought to be ceasing.”

He says the union will be looking at the coroner’s recommendations.

A spokeswoman from Safe Work Australia, an independent statutory body, says there is already a “model code of practice” for those working in hot environments, although it doesn’t stipulate a temperature at which work must stop.

Between 2005 and 2014, 13 workers died in Australia from being exposed to “environmental heat”. Of those deaths, five were in Queensland.

The spokeswoman says Safe Work Australia would consider any proposal put forward by an industry representative.

Climate and Health Alliance president Dr Liz Hanna says it is plausible that, in 10 to 20 years, our “hottest summers” will become the norm and Australia has to become a “heat-aware” society.

She says Australians tend to overestimate their capacity to cope in hot conditions and the decision of whether to stop work needs to be taken out of the hands of the individual.

“We think we’re tougher than we are,” Hanna says.

“The other thing is people often think it’s the little old ladies or the babies who are at risk. But what actually generates the heat is … working muscles. It’s the big beefy boys who are making a huge amount of heat, so they need to be wary.”

But Hanna says setting a blanket cut-off temperature could be problematic and should be “nuanced” by the location.

“I think if we launch in and say ‘everyone downs tools once it hits x’, you’ll find it’ll be too rigid,” she says.

“And if it’s rigid then the rules don’t work – people will break them and you end up losing the battle. I think it needs to be more nuanced for that locality.

“That’s why I’m advocating that people need to work together and be reasonable and not push them until they die just to save a buck – but don’t send the company broke because it’s a bit unpleasant.”

Last month the UN released a report warning rising heat meant elevated health risks for workers.

Hanna has worked with industries to develop heat policies and believes there will be a shift towards more night-time work in the future.

While the coroner’s recommendations focus on heat management for workers, a senior emergency medicine specialist Dr David Rosengren, who was not involved in the inquest, says dilutional hyponatremia is not a heat-related condition and could happen at any temperature – though he says it is more common in hot environments because people are encouraged to “drink water, drink water, and drink water”.

He says dilutional hyponatremia develops when a person’s water consumption exceeds their body’s ability to pass the fluid.

While often difficult to diagnose, Rosengren says people have died in the past after drinking too much water at endurance events like ultra-marathons. In 2010, he travelled to Papua New Guinea to investigate a spate of deaths on the Kokoda Trail.

He says diagnosing the condition is complicated because symptoms for dilutional hyponatremia and dehydration are almost exactly the same but their treatments are vastly different. Asking how much water a person has drunk is critical to discerning it.

“If (Glenn) died from dilutional hyponatremia, it is absolutely critical that the message about water consumption is key for mining companies and emergency services to understand,” he says.

“If the cause of death was dilutional hyponatremia, then the (inquest’s) recommendations that focus on heat stroke may cause confusion.”

Jenny Newport says her son’s death and the past three years leading to the inquest have been extremely difficult for the family, who still have questions about the actions taken the day Glenn died.

“There were lots of issues that we felt the company …(had) not taken a duty of care,” she says.

“We talked to the admitting doctor.

“He said he was fuming they hadn’t brought Glenn in earlier. He knew exactly what it was – even before the post-mortem.

“He more or less said that if Glenn had been brought in earlier … he would still be alive.”

McConnell Dowell released a statement after the inquest findings, offering their sympathies to Glenn’s family and saying they endorsed the recommendation for an industry code of practice to “avoid a similar tragic death occurring”.

Any code of practice, however, will need to differentiate between the dangers of heat stress and dehydration and dilutional hyponatremia from drinking too much water.