How Queensland, in 1916, was the first state to celebrate Anzac Day

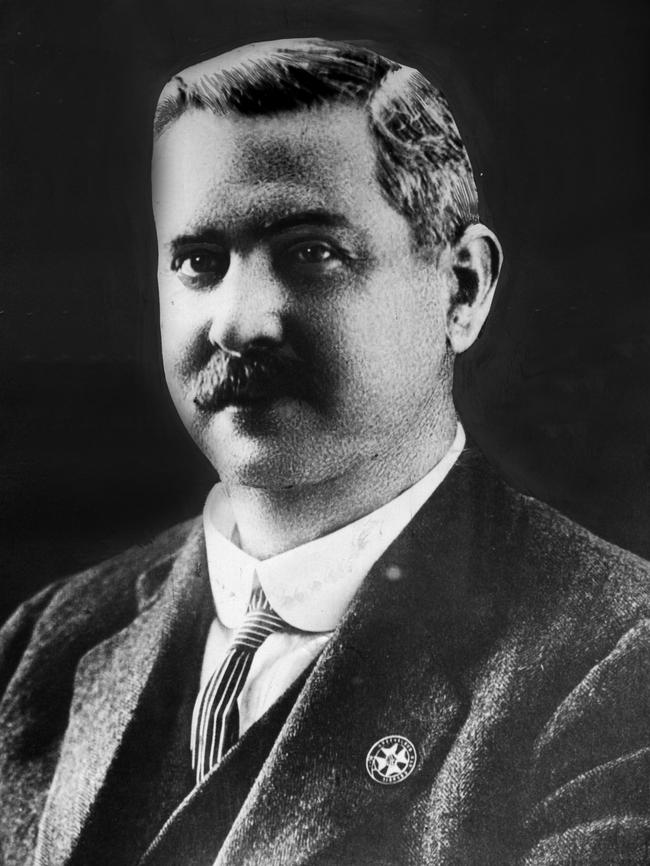

On February 3, 1916, in the office of Queensland Premier T.J. Ryan, the question of Gallipoli and how on earth to commemorate such a horrifying event was raised. The answer was, arguably, why Anzac Day remains still resonates with Australians to this day.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE date was February 3, 1916, the scene was the Brisbane office of Queensland Premier T.J. Ryan, the subject was Gallipoli and the question was: “How on earth does a nation commemorate such a horrifying event?’’

The answer, provided partially by the still largely obscure historical figure of Church of England clergyman, David John Garland, was a solemn ceremony incorporating church and state and offering an opportunity for ordinary Queenslanders to feel somehow integral to the process.

Just over one century on Australia still follows an Anzac Day ceremonial tradition which Queensland can now credibly claim to have given birth to.

Around the nation there were many attempts to recognise the tragic events at Gallipoli in the year following the aborted invasion of that Turkish Peninsula in April 2015.

But it’s now recognised by many historians that it was here in Queensland the first attempt to formalise and nationalise the commemorations got underway, and even the United Nations has taken steps to formally record the state’s role.

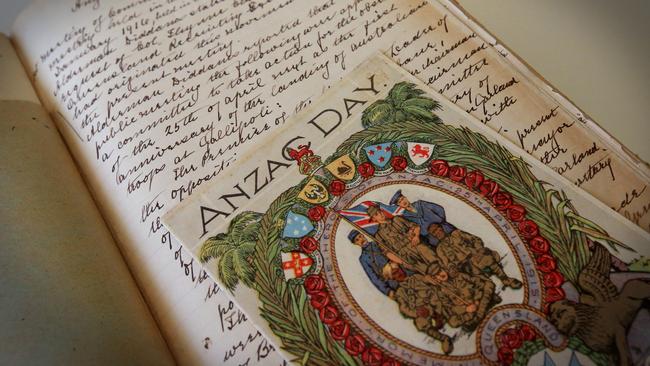

Last month the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) inscribed the minute book of historic meetings of the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee, including the one in T.J. (Tom) Ryan’s office, into the “Australian Memory of the World Register”.

The Anzac Day Commemoration Committee Minutes and Suggestions 1916-1922 – the property of the State Library of Queensland – is now a vital historical document opening up a portal to our past, bringing to life the manner in which we faced down one of the most traumatic, and transformative, events in Australian history.

Robyn Hamilton, Lead of the Collection Building Team at the John Oxley Library, says the book contains the words recording how Queensland community leaders grappled with the dilemma of recognising Gallipoli.

“They were looking at ways of honouring all the young men who had perished in the Dardanelles,’’ says Robyn who also sees the UNESCO recognition, which followed a 2018 submission, as a major step in formalising the reality of Queensland’s role in Anzac Day.

“We are delighted this unique piece of Queensland history has been recognised nationally.’’

The book clearly records that at the February 3 meeting in Ryan’s office, following a public meeting at the Exhibition Hall on January 16, a decision was made about Gallipoli.

“It was decided the first anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli shall be suitably celebrated in Queensland and the other states be invited to similar action,’’ one entry reads.

“The chief object of the day will be the commemoration of our fallen heroes and for the honour of our surviving soldiers.’’

The dawn service was still in the future – a church service was to be held at 9am with representatives of all denominations present.

In the afternoon there was to be a march and that night there was a series of ceremonies in which affirmations of loyalty to Empire and pledges of allegiance to the British Crown were made.

Dr Mark Cryle, author and honorary researcher with the University of Queensland who completed his doctorate on Queensland’s first Anzac Day commemorations, says even though other states actively sought ways in which to address the first anniversary of the Anzac landing, there was little doubt the Brisbane meetings were the first attempt to give shape and form to the day with an eye to a national perspective.

“Queensland was one of the first places to try and codify Anzac Day,’’ he says.

‘’It (Anzac Day) was certainly promoted actively in Queensland.’’

Cryle says Canon David John Garland was an important figure in the creation of Anzac Day but not necessarily central to the process.

Garland was secretary of the Anzac Commemoration Committee but also secretary of the Queensland Recruiting Committee, as were many of his clergymen colleagues.

“These were hard line Empire men, and they faced a dilemma – how do we commemorate this terrible event while at the same time use it as a recruitment tool?’’ Cryle says.

While we in the 21st Century might see the first Anzac Day through a romantic prism of a nation united in grief, the mood of the day was a vastly different affair.

“The war was becoming a bit like Vietnam,’’ says Cryle. “There were many people coming out against it by 1916.’’

Canon David Garland, the architect of Anzac Day, was on a mission for king and country

Mooted by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, the Dardanelles plan was designed to take the British naval fleet through the narrow strait of the Dardanelles that severed Europe and Asia in northwest Turkey and then seize Constantinople.

It was a total disaster.

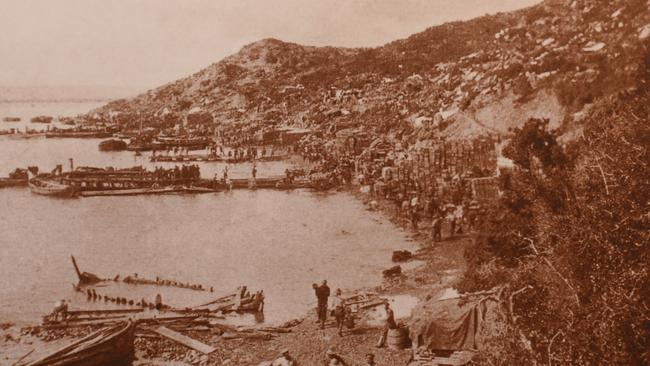

Its opening move, to attack and secure the Gallipoli Peninsula on April 25, 1915, failed at the cost of more than 130,000 lives, more than 8000 of them Australian.

The evacuation which ended on December 20 was widely regarded as a tactical success.

“The fact is it was a botched job,’’ Cryle says.

“’The best thing about it was the retreat.’’

Australians were none-the-less inspired by the battle, largely because of newspaper reports penned by British journalist Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett who painted the Australians and New Zealanders in heroic prose including: “The Australians rose to the occasion. They did not wait for orders, or for the boats to reach the beach, but sprang into the sea, formed a sort of rough line, and rushed at the enemy’s trenches.’’

Yet even in Canberra the then acting prime minister George Pearce, leading the country while PM Billy Hughes was preoccupied with the Imperial War Cabinet in London, was reportedly doubtful about creating a ceremony to commemorate April 25.

“Let’s wait until we win one,’’ he reportedly replied when asked about a commemoration of the Gallipoli Campaign.

In Brisbane Garland and his clergymen colleagues were determined to press on, attempting to finesse a ceremony which would assuage the grief of the families and loved ones of the fallen, yet at the same time act as a subtle recruiting tool.

While young Australian men stormed recruiting offices around the country in 1914, the glamour of war had faded as the death toll rose, and the reality of the wounded began to be apparent in the city streets.

Looming on the horizon were the two conscription referendums which, according to former prime minister Malcolm Fraser, divided Australia like no other issue in history, including the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in 1975.

The first referendum in October 1916 was voted down narrowly. The second in December 1917 was rejected with a bigger majority, in no small part to the influence of the Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, Dr Daniel Mannix, a towering “Celtic Chieftain’’ who had a powerful hold on his Irish Catholic congregation nationally.

The first Anzac Day went ahead in the form of a Brisbane march, but it was not an overwhelming success. The sight of the many wounded who were also paraded distressed many onlookers, and the following year, far fewer people turned up.

Cryle says while many Australians may view Anzac Day as an immovable institution, as solid as the Uluru rock in the centre of the nation, the fact is it has swayed in out and out of fashion through the decades.

In the 1960s and 70s the rising tide of progressives in the Baby Boomer generation saw it as an anachronism, an attitude brought to theatrical life by Alan Seymour in his play The One Day of the Year.

The 1980s saw a revival of interest in the day.

By the mid-1990s, with the decade-long government of John Howard in power, Anzac Day was embraced perhaps more fervently than at any other time in history.

Today it is our most important national day, eclipsing January’s Australia Day.

And while there are a tiny minority who disapprove, labelling it a celebration of violence or dismissing it as a relic of a colonial past, the overwhelming majority of Australians staunchly defend it as a crucial commemoration.

“You could stand up in a pub and say all politicians are bastards and most Australians would buy you a drink,’’ says Cryle.

“But stand up and attack Anzac Day and you might find yourself in real trouble. You simply do not disrespect Anzac Day.’’