How a Queensland grazier helped end World War I with a victory over Germany that saved millions

ONE hundred years ago on Anzac Day, a grazier from Queensland and a pugnacious solicitor from Melbourne worked together to change the course of world history.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ONE hundred years ago on Anzac Day, a grazier from country Queensland and a pugnacious solicitor from Melbourne worked together to change the course of world history.

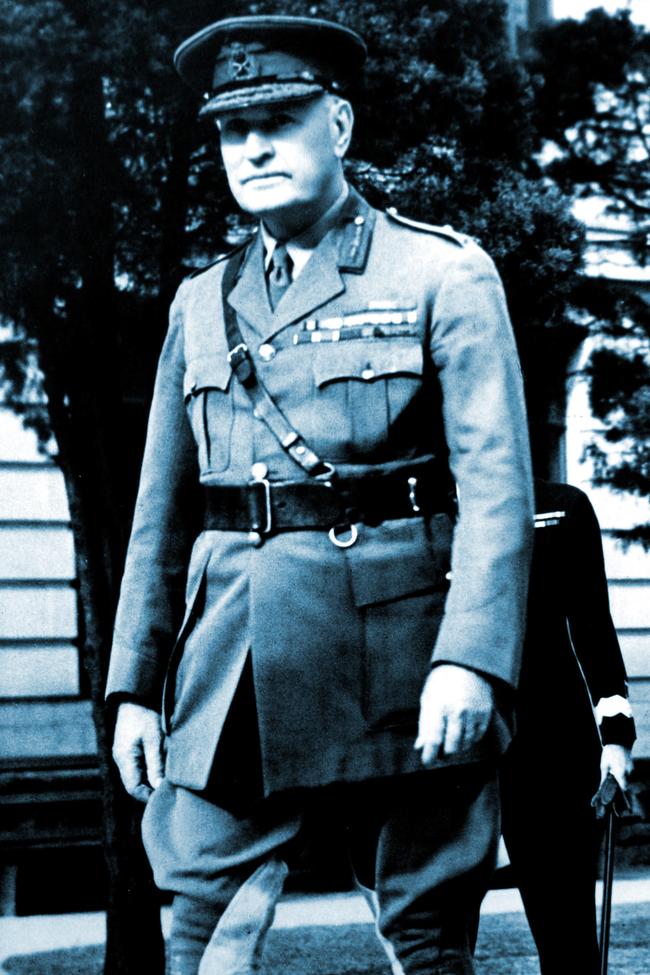

Thomas William Glasgow and Harold Edward “Pompey’’ Elliott orchestrated the stunning victory by Australian troops at Villers-Bretonneux in France that knocked the wind out of Germany’s last great thrust of World War I. Millions of lives were saved as a result. Australian commander John Monash hailed victory there as the turning point of the Great War, “a magnificent feat that finally destroyed the German hopes of a decisive victory’’.

While the slaughter and sacrifice on Gallipoli has been commemorated each year since 1915, the courage of the Australian troops at Villers-Bretonneux three years later led to a key victory against enormous odds as Britain and France feared they were on the brink of annihilation. The Australian National Memorial in France is located just outside the town and in front of a cemetery where 779 Australian soldiers were buried after the desperate struggle to take back Villers-Bretonneux from German hands. The local school was rebuilt in 1927 with donations from Victorian schoolchildren, many with relatives buried there after fighting to liberate the town. Above every blackboard is the inscription, “N’oublions jamais l’Australie” (Let us never forget Australia).

Glasgow is regarded as the most successful soldier Queensland has produced. His bronze statue is now at Post Office Square in Brisbane after several moves and overlooks the annual Anzac Day march. At the height of the battle for Villers-Bretonneux, with his 13th Brigade surrounded on three sides, the Germans sent Glasgow a message demanding that he surrender. He famously replied “Tell them to go to Hell.’’

Europe was already in a state of torment.

By the time of the northern spring of 1918 the British naval blockade had caused mass starvation in Germany and the lack of quality food for both man and beast resulted in constant suffering. Influenza, dysentery, typhus, tuberculosis and scurvy ravaged a depressed population.

On the front lines, the rations of German soldiers were reduced. Bandages were in such short supply that crepe paper was used to dress wounds. In Germany’s occupied territories every available source of metal – kitchen utensils, doorknobs and household fixtures – was melted down to make weapons and ammunition. Church bells and organ pipes were requisitioned, even plumbing from German homes. Pack animals were skin and bones. The pre-war death rate of children had doubled.

But with the fall of Russia, German leader Erich Ludendorff had more than four million men at his disposal. He planned a massed attack along the River Somme in March, to separate the English and French forces and create a gap through which the Germans could attack the vital ports on the English Channel.

He planned – Vernichtungschlact – the battle of annihilation, which Winston Churchill labelled “the mightiest military conception and the most terrific onslaught which the annals of war record’’.

At dawn on March 21, 1918, having rehearsed his movements perfectly, German artillery maestro Colonel Georg Bruchmüller, unleashed hell at 4.40am, in the biggest single artillery attack ever seen. The German guns signalled the start of Operation Michael, firing together all along the front of the British lines: 4000 field guns, 2600 heavy guns and 3500 trench mortars.

For five hours, high explosive shells, shrapnel and poisonous gas bombs hit the British troops in a great cacophony of destruction. Those not killed by the blasts or left choking and reeling by the gas were in a state of shock.

The French countryside looked like one enormous cloud of smoke and fire and like some demonic vision, 72 German divisions surged forward through the thick fog, fired by with a mixture of anger, bloodlust and elation at a looming victory.

By the end of the day, the Western Front was shattered. There were nearly 20,000 Allied troops dead and 35,000 wounded. After the second day Britain’s 5th Army was in retreat. The 3rd soon followed.

Royal Flying Corps pilots trying to stop the German advance with aerial bombing reported that from every town in the area huge plumes of smoke rose to 2500m. Refugees fled covered in powdery dust from the smoke and explosions. British officers were told to use their revolvers to check panic among their troops. Before long the attack cost the British 177,739 casualties, with 75,000 men taken prisoner.

Within a period of three days, the English Army suffered the greatest defeat in its history. Enter Glasgow and Elliott.

Glasgow was a 41-year-old father of two small girls. Born at Tiaro, near Maryborough, Queensland, he was educated at One Mile State School in Gympie and then Maryborough Grammar. After leaving school he worked in Gympie as a clerk for a mining company and then a bank. He volunteered for the Boer War and served as a lieutenant in the 1st Queensland Mounted Infantry Contingent at the relief of Kimberley and the occupation of Bloemfontein, where the Australian poet Banjo Paterson was based as a war correspondent.

Back at Gympie he took over his father’s grocery store and by the time fighting broke out at the start of World War I he was among the first Queensland volunteers, despite now running a cattle station in central Queensland. He distinguished himself in battle on Gallipoli and was in charge of the 13th Brigade by the time the Germans launched Operation Michael in France.

Australia’s Official War Historian, Charles Bean, described Glasgow as having “keen blue eyes looking from under puckered humorous brows as shaggy as a deerhound’s; with the bushman’s difficulty of verbal expression’’. Bean said he had a fiery temper, “but a cool understanding and a firm control of men.’’ He could “by a frown, a shrewd shake of the head, or a twinkle in the eyes screwed up as if in the glare of the plains, awaken in others more energy than would have been evoked by any amount of exhortation”.

The Germans besieged Villers-Bretonneux in the first week of April 1918, positioning them well for a charge to take the vital rail link of Amiens. On April 24 they took the town after the first ever battle between opposing tanks.

Glasgow’s 13th Brigade was ordered to form the right wing of a counter-attack to recapture the town, in conjunction with the 15th Infantry Brigade under Brigadier General “Pompey’’ Elliott, another Boer War veteran who was a Collins Street solicitor in Melbourne during peacetime. Elliott, 39, was outspoken, impulsive and excitable. Late in the war he was shot in his well-padded left buttock, but continued to direct his men as he stood on a prominent mound with his trousers around his ankles while underlings tended to his backside. There were catcalls about the “massive magnitude of his posterior’’ and one of his colonels said that seeing “Pompey with his tailboard down having his wound dressed’’ was one of the great sights of the war. After he saw a British officer allegedly looting champagne as his troops retreated, Pompey ordered that any of his men caught doing the same would be publicly hanged and left dangling as a warning to others.

Glasgow could be a hard man, too. He campaigned unsuccessfully for the Australians to use the firing squad for deserters as the British and Kiwis did but for his brave and loyal troops he was a fearless and staunch advocate. When the British ordered Glasgow to lead his 13th across the enemy’s front at Villers-Bretonneux he argued that the timing and angle of attack would make it a suicide mission. So at Glasgow’s insistence the battle began in the dark on April 24 at 10pm. With the British in support, the 15th struck from the north and the 13th from the south, meeting at the town’s eastern edge. Much of the planning had been done by Major-General Talbot Hobbs, an architect from Perth.

Sergeant Andrew Fynch, a Melbourne plasterer who would die a few weeks later, recalled that “with a ferocious roar and the cry of ‘into the bastards, boys’,” Elliott’s men came down on the Germans before they realised what had happened.

“They screamed for mercy,’’ Fynch said, “but there were too many machine guns about to show them any consideration. Each man was in his glee and old scores were wiped out two or three times over.’’

Though vastly outnumbered, the Australians drove the Germans from Villers-Bretonneux and the adjacent woods on Anzac Day 1918. Lieutenant Clifford Sadlier, a commercial traveller from Subiaco, was later awarded the Victoria Cross after mounting a grenade attack.

The Australian effort was a spectacular success even though 2473 Diggers were killed or wounded. The Australians effectively ended the German advance towards Amiens and are still revered at Villers-Bretonneux.

In a speech after the war the mayor of that little town lauded “the valorous Australian Armies, who with the spontaneous enthusiasm and characteristic dash of their race, in a few hours drove off an enemy who had 10 times their numerical strength … Soldiers of Australia, whose brothers lie here in French soil be assured that your memory will always be kept alive, and that the burial place of your dead will always be respected and cared for.’’

The esteem in which the Australian soldier is held in France was best illustrated by the recollections of Bean.

The Australian troops had arrived in the vicinity of Villers-Bretonneux in late March to find scenes of utter chaos after the German artillery had unleased their version of Armageddon. Wild-eyed English soldiers were in retreat and panicked French civilians streamed westward towards the coast with their belongings in “wheelbarrows, hand carts and farm wagons’’.

All of them looked starved and broken with fatigue, the women, young and old, dressed in their mourning black.

“For as far as the eye could see,’’ Bean wrote, “came carts lurching with towering loads, precious mattresses, bedsteads, washstands, picture frames, piled together with chairs, brooms, saucepans, buckets, the aged driver perched in front upon a pile of hay for the old horse; the family cow – and sometimes calves, or goat – towed behind by a rope or driven by an old woman or small boys or girls on foot. One old man, whose wife was too sick to walk, was wheeling her before him in a barrow.’’

In Heilly, 10km from Villers-Bretonneux, one Digger sat cleaning his rifle by the side of the street as he told a local woman that there was no need to run any more. “Fini retreat, Madame,’ ” he said in the best French he could muster. “The Australians have arrived, and there are many of us.”

Grantlee Kieza is the author of bestseller Monash: The Soldier Who Shaped Australia