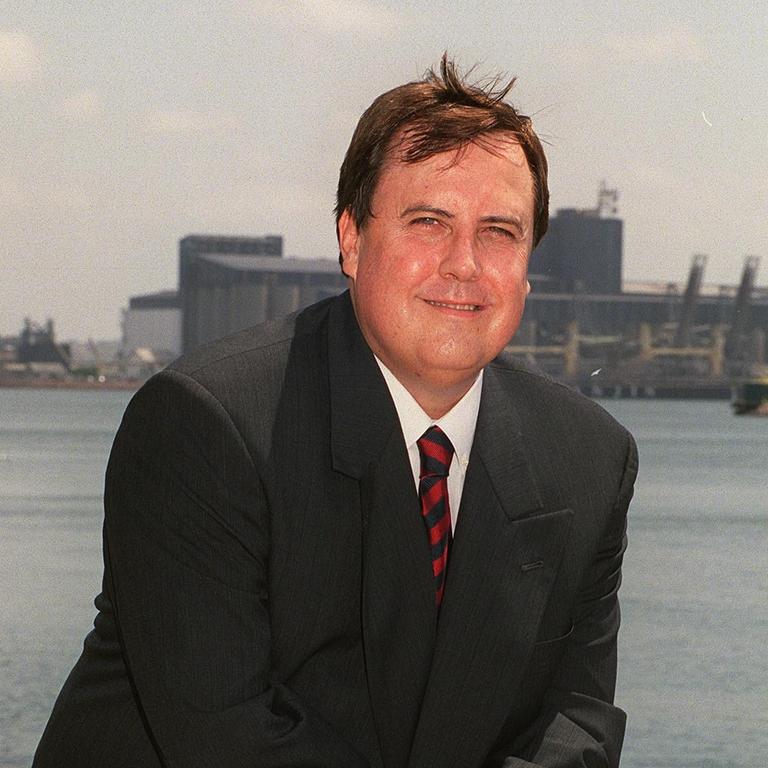

High Steaks: Inside the impossible to believe rich world of Clive Palmer

He is rich - cartoonishly rich - outspoken and powerful - and at this federal election, he simply cannot be ignored. This is the true story behind his meteoric rise.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Clive Palmer is not merely rich but incomprehensibly so, as in:

“Clive, do you still own that Rolls Royce?”

“I own 110 of them.’’

He’s cartoonishly rich, like Richie Rich is rich, his wealth eclipsing that of King Solomon whose estate, audited in the Hebrew Bible, did not include anything resembling that $120 million Global Express 6000 Bizjet residing in a Gold Coast hangar, waiting to spirit Clive off to any destination he may choose on this planet, without stopping, not once.

There’s no five-hour wander through Changi Airport waiting for a connecting flight for Clive.

Not when you’re the man owning the biggest slice of freehold land in the Tahitian paradise of Bora Bora, not when you holiday in the French Alps where a hotel cost $28,000 a night, not when a handbag costing $14,000 catches the wife’s eye, and you just go ahead and buy it for her because... “what the hell, it’s only money’’.

You don’t live like a mere mortal when you cruise the Mediterranean in your own ship and stroll through marble hotel foyers where the world’s billionaires (which Forbes calculated in April last year as numbering 2781, putting Clive inside an exclusive club limited to something like 0.0001 per cent of the entire global population) gather to sip $500 whiskey and do their deals.

Incidentally, he doesn’t own 110 Rolls Royce cars. He throws the British-made Bentley into the same category as the Rolls and possibly a few more historically prestigious English cars but what is abundantly clear to me, as he attempts to explain the make-up of his classic car collection, is that he has no real idea on how many vehicles he owns.

They may be something of a passion, yet they serve him, as probably everything within his reach does, as a profitmaking enterprise.

He figured out a long time ago that you’re not allowed, under federal tax law, to write off depreciation on your Honda Civic when it comes to your annual tax return.

On the other hand, you’re not obliged to pay tax on the capital gain in the unlikely event the Civic’s value rises over the course of the year.

Clive notices these sorts of things.

He has made great sport of investing in exotic cars and enjoying the tax-free profits on their sale but the Australian “Monaro and GT HO Falcon’’ crowd might be disappointed to learn his unquestioned patriotism doesn’t cloud his judgment – it’s the classic European and American muscle cars where the real profits lie.

How does one find oneself in this position? Buying Ferraris like matchbox cars? How does a person get to own that 56 metre ocean-going super yacht crewed by 15 people sitting at the Southport yacht club along with the other one, slightly shorter, along with the other two, no more than 25 metres, serving as runabouts when he wants to take a quick cruise on Moreton Bay?

How does one get to know the Kennedys of Massachusetts?

Sitting at Red’s Kitchen and Bar at the Sanctuary Cove Village, eating fillet steak and chips, a slimmed down Clive cheerfully romps through his extraordinary past and, at 71, is happy to peer into what he sees as his still fascinating future given Covid didn’t kill him, as several doctors predicted it would.

How did he make so much money?

“Love,’’ is his answer.

When he was young, whippet thin and a talented runner fast enough to set a record for the 400 metres that stood for decades, (actually true) he fell in love with a woman.

Like many men who have found themselves in a similar predicament across several millennium, he swiftly found only one thought burning into his brain:

“How do I impress Her?’’

He was 19, a largely broke University of Queensland student, living in a Brisbane Salvation Army Hostel where he received room and meals for acting as a carer for about eight kids who were what was then termed “wards of the state’’.

He was also noting that girls in his lectures preferred to go out with richer boys who drove the sort of Ferraris he would soon own as investment vehicles.

By his own admission, he was also lazy, but he knew that if he was going to ask “Sue’’ (his first wife, now deceased) out to restaurants he would need to make money over his summer holidays so he picked up a Courier-Mail newspaper, looked at the job advertisements, and settled on a real estate position which offered a $200 a week retainer plus commission.

“I never thought I would get the commission, but I figured $200 a week for a few weeks would give me the money I needed.’’

He rang the real estate company and was told they wanted someone aged over 30, not 19, so Clive did what seems to be a very Clive-like thing.

He rang them back, affected a deeper voice, told them he was 30, and got the job.

It was a revolutionary age in the art of selling. Thirty-five years before Clive made that call the American Dale Carnegie had published what remains a best-selling book, “How to Make Friends and Influence People,’’ sparking a massive tide of books and management classes and entire disciplines selling new sales principles which swept through America and much of the western world.

The real estate firm wanted Clive to participate in one of these newfangled sales courses and, while the old timers who lounged at their desks occasionally picking up the phone to make a sale scorned the new approach, Clive learned it by heart, following each and every step much like a child follows a painting by numbers kit.

He estimates he made $450,000 (in 1971 money) within four months. It was enough to start buying blocks of flats of his own around Auchenflower and perhaps more importantly, enough to inform him of that defining characteristic dwelling within – he was a genius at selling.

His parents were appalled, wanting him to complete his Art/Law degree and settle into suburban respectability rather than become a real estate tycoon.

But Sue from Jandowae in the Western Downs married Clive, and that, in his mind, sealed the deal. He knew he was on the right track.

Those of us who are poor, such as myself, can’t look at someone who is super rich without thinking they must have done something dishonourable to accumulate such outrageous wealth. It’s a wonderful balm for a resentful mind.

“You have to do people over if you are going to make the sort of money you have,’’ I suggest, and Clive just smiles knowingly.

Real estate is a tough game, often with underhand dealings accepted as part of the rules of play, but Clive insists that his own self interest kept him out of serious trouble.

He remembers the enormous commissions offered on the sale of land that he knew was substandard, or even worthless, yet owned by someone desperate to get rid of it and willing to pay handsomely any agent who would close the deal.

“They might offer you two to three times the commission you would normally get if you just sold that land, but I had the discipline not to do it,’’ he says.

It was, he concedes, not so much an innate sense of morality as good business sense.

“You find they often go together,’’ he says.

You can be the “spiv’’ and take the million dollar commission, or you can settle in for the long game, and make yourself $20 billion.

He seems proud that, even as he branched out of real estate into mining leases and a host of other money making ventures, he was never one of those corporate heavyweights who went broke and took thousands of mum and dad investors with him.

So how does Yabulu sit with all this?

That nickel refinery he took over in Townsville after being approached by then Queensland premier Anna Bligh when BHP was about to shut it down, still irks him.

When Queensland Nickel Pty Ltd terminated 237 workers in January 2016 it was Clive who became the villain of the piece for allegedly failing to pay workers’ entitlements.

When the administrator was appointed Clive said he had to follow the rules as they assessed if the company had enough to pay entitlements which were actually covered by the Commonwealth to begin with.

After the administrator had finished the process he covered the cost incurred by the Commonwealth and, Clive insists, no one, not the taxpayer or the worker, was left short changed.

“There was no attempt by us to run away from paying those workers their entitlements.’’

As for the latest chapter in that strange, guerrilla campaign he seems to enjoy playing with the major political parties, you can be assured “Trumpet of Patriots’’ which he chairs and which grew out of the Country Alliance founded in 2004, will be on the ballot with as many as 160 candidates ready to go when the election is called.

Why? I ask, does he keep offering these little electoral kidney punches to the ruling parties?

His roundabout answer is that this country is going to the dogs. Low productivity, a ballooning public sector and a self interested political class risk turning a wealthy first world country into a poverty stricken backwater, and he can use his presence in the field to steer debate to areas he thinks need addressing.

He donated $5 million to Foodbank cash last month. Don’t be too impressed. If he donated that money Monday morning, his earnings would have ensured he’d have made the cash back by the following Thursday morning, plus an extra one million dollars on top.

But he quotes Foodbank Australia Chair Duncan Makeig who points to an internal report suggesting 3.4 million Australians experienced food security in the past year.

“That is not the Australia I know,’ he says.

A still observant Catholic who tries to get to Mass once a week, he still believes our lives have a greater purpose than readily meets the eye.

God, he suggests, is simply a name for the force giving itself expression through you and me, and he wants his own rather unique version of that force to leave a legacy of good rather than evil behind.

He has a few heroes – one is Colonel Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame.

The Colonel, Clive notes, only truly gained traction with his chicken empire when he was 63, watching it spread itself across the world in his 70s and 80s.

Don’t expect a Palmer Chicken franchise but Clive, God’s own instrument on earth, may have a few surprises left for us yet.

(Medium fillet steak, chips salad mushroom sauce) 10 out of 10.

Read related topics:High Steaks

.jpg)