Griffith University “cure” cervical cancer in mice

Griffith University researchers say they have made a “significant breakthrough” and have “cured” cervical cancer in mice.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

QUEENSLAND researchers have used gene-editing technology to “cure” mice of cervical cancer in what they believe is a world first.

The Griffith University scientists are working towards human trials of the gene therapy in the next five years and are also researching the technique as a potential treatment for some head and neck cancers.

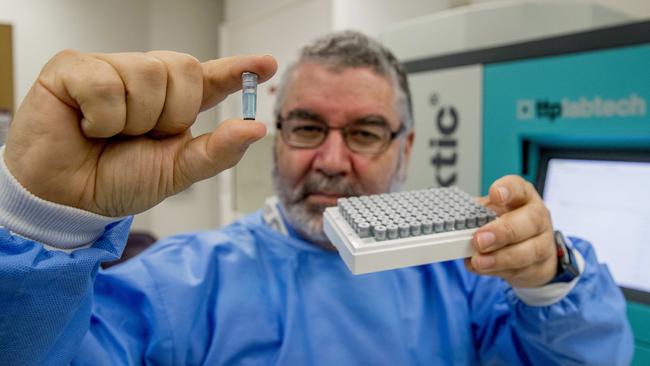

Virologist Nigel McMillan said the researchers used a gene-editing tool, known as CRISPR-Cas9, to target a gene called E7 found in cancers caused by the human papilloma virus.

QLD RESEARCHERS DEVELOP POTENTIAL NEW TREATMENT FOR TOXIC SHOCK

GRIFFITH UNI RESEARCHERS TARGET THE TERMINATOR

E7 is known as an “oncogene” because it acts as a driver in HPV-related cancers, promoting tumour growth, but is not present in normal cells.

Once CRISPR-Cas9 is delivered to tumour cells by nanoparticles injected into the bloodstream, it searches out the E7 gene and then acts like a pair of molecular scissors, cutting the gene in two.

Professor McMillan, of the Griffith University-based Menzies Health Institute, said that when the cell tried to repair the gene by introducing some extra DNA, it was like adding too many letters to a word, preventing it from being read properly.

“It stops the gene from being recognised and because the cancer must have this gene to produce, the tumour dies,” he explained. “It’s quite remarkable. We’re really excited about the potential of this technology.

“Normal cells from a growth point of view seem unharmed and the tumour cells die.

”We think this is a really significant breakthrough. It also shows how good Australian science is. We’re pinching ourselves a little bit.

“To the best of our knowledge, we’re the first in the world to actually cure cancer with CRISPR in a pre-clinical model.”

The researchers have applied for a grant to refine the technology and develop it for human trials.

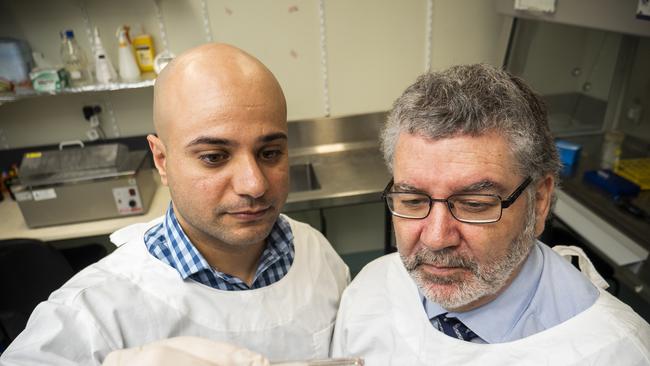

But Professor McMillan, who worked with medical doctor Luqman Jubair on the project, admitted the technology “is not without its issues” that would need to be studied further before they could test the treatment in people.

He said they planned further work to make sure the treatment was only affecting cancerous cells, and not normal tissue.

Professor McMillan expects that if the technique works as a treatment for cervical cancer in women, it could be adapted as a therapy for other cancers as long as genetic tumour drivers were able to be identified.

Although CRISPR was developed by overseas scientists, the Griffith researchers have adapted its use to treat cervical cancer in an animal model.

Other scientists are using the technology in an attempt to repair genes in the hope of creating treatments for disorders such as cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy.

The Griffith University researchers’ work is published in the journal, Molecular Therapy.