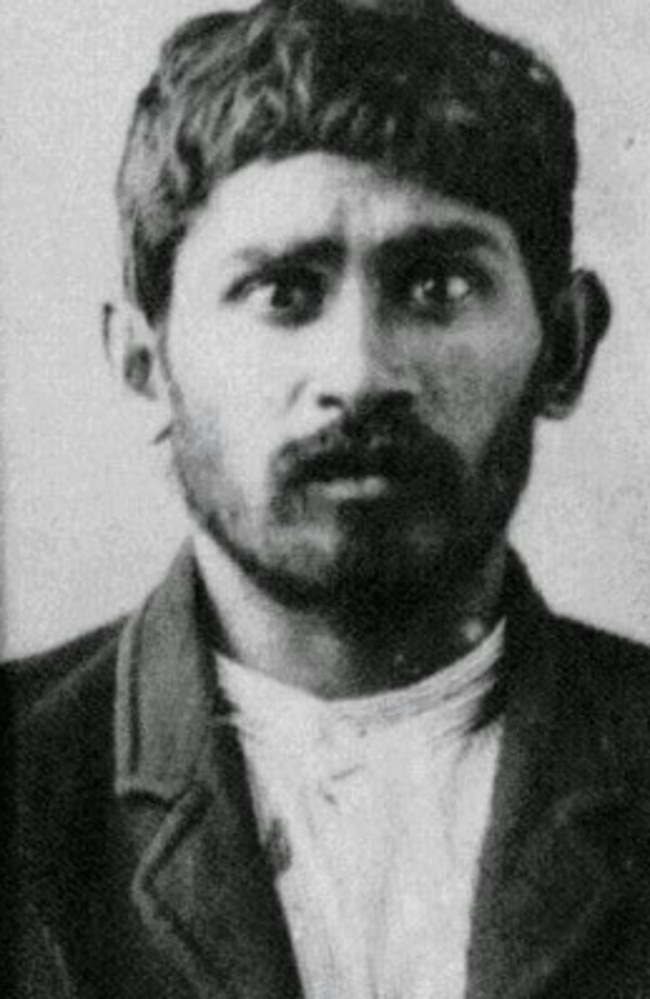

George David Silva responsible for one of Queensland’s worst mass murders in Mackay

HIS family had been missing for hours ... then the farmer looked in the most obvious place. Dead, piled together, the Holy Book atop their bodies. The adults were shot, the children suffered a fate much worse.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

GEORGE David Silva, his legs and arms bound, stood on the wooden trapdoor of Queensland’s notorious Boggo Rd jail awaiting death.

Only his final words hung between him and the noose. Only moments to live. Then life, as short as it had been, would be gone.

Silva trembled and took one of his final breaths. Only words would delay the hangman now, so he found many of them.

“I desire,” he began, “to thank the superintendent of his jail and all the warders for all their kindness in coming to see me and visiting me and leading me to the throne of God.”

He bemoaned the justice system, the police and the witnesses who had spoken out against him. They’d told lies. Given false oaths.

“They did not give me justice at all,” he said.

He spoke about God. Asked his friends and family to be good Christians in case they suddenly found they, like he, had run out of time.

Then he began to pray.

“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I shall fear no ill,” he said.

He repeated the passage, again and again. “Thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me,” he intoned.

And there was more from the Bible.

“There is another chapter,” he went on, journalists scribbling furiously, turning page after page of their notebooks, “I have just been reading this morning the 14th chapter of St John. I hope some of you, friends, will read that and see what it says.”

Silva recited the chapter. Prayed some more. Recited again the 23rd psalm. A newspaper man would later describe the lengthy exhortations. A slight hesitation. Then: “And dear friends, I tell you now, I say to you a merry goodbye.”

But he still had more to say.

“I am going to Heaven. I am going now. I am going to Heaven.” This he repeated over and over.

Twice, prison officials told him he had to stop.

Finally, he was still. The noose was slipped over his head. He began muttering again as the jail’s executioner pulled the bolt that released the trapdoor.

Death was instant.

George Silva was born to Sri Lankan parents and raised just outside of Mackay. He developed a passion for the church and would lead prayers. He became known as a preacher of sorts and a “pet” of the church.

As an adult, he found work as a farmhand on a property at Alligator Creek, 20 miles out of town.

His employer was a property owner named Charlie Ching, a Hong Kong born man who’d married a white woman named Agnes.

They lived in a corrugated iron home with a dirt floor. The kitchen was in a separate structure, some distance from the main house.

But to Silva, who had nothing at all, the married couple and their brood of children were rich beyond belief.

He’d wanted to marry their daughter Maudie. She was 17. He told a neighbour Mr Ching would give him a plot of land come Christmas and he’d build a house so they could start a family.

“You can’t marry,” the neighbour told him.

“You got no money. You got no blanket. No decent trousers. How would a girl like to marry you like that?”

His proposal was rejected by the Chings. The farmhand had nothing to offer their daughter. There would be no wife, no children, no plot of land and no newly built house.

On November 17, 1911, Charles Ching arrived home to find Silva waiting out the front for him.

The door to the house was locked and Silva explained Agnes and the children were out visiting a neighbour.

With no way to get inside, the pair retreated to the kitchen quarters and sat down to have tea.

But as night fell and there was still no sign of his wife and children, Charles’ concern grew.

He left to search for them, knocking on the doors of neighbouring properties to see if anyone knew where they were.

Nobody had seen them, but Charles was told some disturbing news.

Shots had been heard from the direction of the Ching house.

Charles rushed back and he and Silva broke in through a side window.

His family had been there the whole time. Agnes and Maud, along with five-year-old Hughie and one-year-old Winnie, were dead, their bodies piled together in the sitting room under a rug. On top of the rug, their killer had placed a bible.

The adults had been shot. The children had been beaten to death against the wall. The room was sprayed in blood. The walls, the windows, the floor. It was like a slaughterhouse.

“Oh Lord, I never saw anything in my life like this,” Silva said.

The farmhand was given a horse and sent to fetch the police.

Two children, Teddy, 10, and Dolly, 8, were still missing. They’d been at school that day but were not in the house with the rest of the family.

Police brought in an Aboriginal tracker named Charlie Deighton and asked him to help them follow the killer and find the children.

He did. The following day, with the help of two other trackers, Charlie found the missing children.

They were about a kilometre from the house. One had been shot. The other clubbed to death.

Charlie also found boot prints that were measured and found to be the same size as those belonging to the farmhand.

Police had already had their eye on him. He’d been acting suspiciously.

Silva had told police he’d spent the night sleeping under a tree near the tram line. But when they asked him to show them the tree, he’d been unable to find it.

Children from the Alligator Creek State School told police they’d seen Silva meet Teddy and Dolly near the house.

It was a small community and it became common knowledge that the farmhand was the prime suspect.

Frightened for his own safety, Silva turned himself in. He took them to where he’d left the gun and showed them the burnt remnants of the clothing he’d been wearing that day.

He claimed two neighbours had helped him murder the family but police dismissed his claims after finding no evidence of any collusion.

People came in their droves to line the streets as Silva was marched, handcuffed, into the courthouse.

Townsville Detective Sergeant Thomas Head gave evidence the farmhand had confessed to the crime.

“Who committed the murders?” he said he’d demanded of Silva.

“You must know something about them. You were there.”

He told the jury Silva had replied: “I did.”

The court heard Silva’s motive had been revenge on the family that had robbed him of his future by refusing to allow him to marry Maud.

Despite apparently confessing to the crime, Silva claimed he’d been beaten into owning up.

The jury took just 20 minutes to find him guilty and he was sentenced to hang.

Silva, who remains one of Queensland’s worst mass murderers, was executed on June 10, 1912, aged 28.

###