Professor Jamie Seymour speaks out on irukandji spread

Queensland’s leading Irukandji expert says the killer jellyfish are gaining ground in the state’s southern waters and fears fatal stings are imminent amid a 15-year failure to fund preventative research.

Fraser Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Fraser Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

An Irukandji expert, who first recorded the presence of the deadly jellyfish off Fraser Island more than 15 years ago, hopes it won’t take a tragedy for the State Government to investigate the spread of the animals down the Queensland coast.

It comes after four children were airlifted to Hervey Bay Hospital after suffering suspected irukandji stings in Wathumba Creek on the island last week.

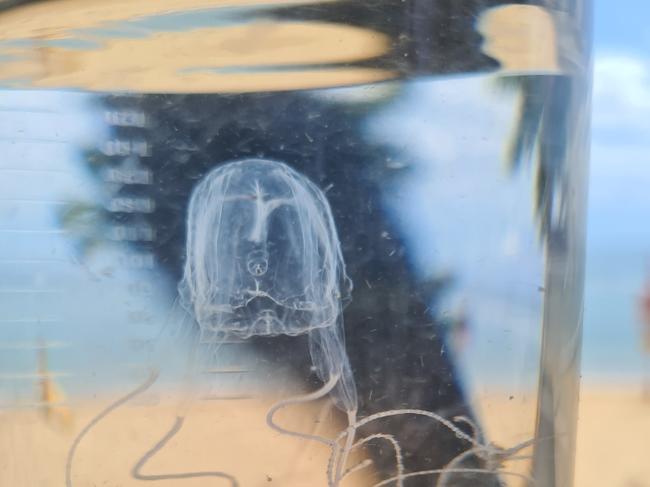

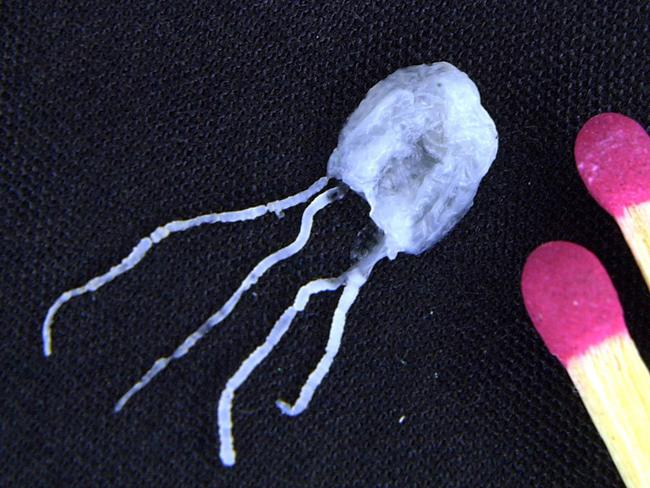

Irukandji are known for their small size and highly venomous sting, which often leads to hospitalisation and can be fatal.

RELATED: Sharks, snakes, stingers? She’s right! Families flock to deadly paradise

Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine Cairns Professor Jamie Seymour said more people were hospitalised in Australia because of jellyfish than both sharks or crocodiles, but the animals attracted little attention or funding for research.

Yet, there were crocodile advisory panels, assessment teams, traps, shark drumlines and research funded by the State Government, Mr Seymour said.

Outside of Cairns however, there was nothing for jellyfish research.

“I mean we would drop everything tomorrow and come down and work ourselves stupid down there if we could find research funding to do it,” he said

“But we can’t. As a result, nothing happens.”

Mr Seymour fears it will take a tragedy to change things.

“I hope that nobody ever gets in a situation where they are in a life-threatening position from an irukandji sting, but I have to say that it is going to happen at some stage down there.”

The remoteness of Fraser Island and limited resources also needed to be considered, Mr Seymour said.

“You’ve got a medivac chopper flying over to pick someone up from a jellyfish sting.

“What happens if there’s two cases they have to go out to, one’s a jellyfish sting and one’s a car accident on the highway somewhere.

“We can't stop car accidents from happening, whereas we can, with some research and working out what’s going on, we can decrease the incidences of being stung on the island.”

In recent years, marine stings off the coast of Fraser Island have become a growing concern and addressing the issue is long overdue he said.

“It was concerning 15 years ago when we found it there,” he said.

“It hasn’t gotten any better.”

Now, Mr Seymour not only believes that parts of the island, such as Wathumba Creek, should be closed for part of the year to avoid potential disaster, but also that this is just the beginning of the spread of the irukandji, which could have a devastating effect on Queensland tourism.

“You’re out of your mind getting in the water there until we have some idea of what’s going on,” Mr Seymour said of Wathumba Creek.

“I am stunned that there has not been a very loud and very coordinated outcry from that particular area that we need research into keeping people safe on that beach.”

In 2017, one of the jellyfish was discovered on a beach at Warana.

“Fifty years ago the southernmost sting for Irukandji was in the Whitsundays and now the southernmost sting is Mooloolaba beach,” Mr Seymour said.

But instead of researching the spread of the animals, the general consensus among decision makers seemed to be that of an emu or an ostrich, “stick your head in the sand and it will go away”, he said.

“It’s coming back in spades now to what’s going to cause major problems.

“What are you going to do when, not if but when, these animals arrive at the Sunny Coast on the main beaches there?

“You’re going to have to shut the beaches, that’s the only option you have and how do you think that’s going to go across to tourism?”

With little data being collected because of a lack of funding, there are only theories as to why irukandji are being discovered further south down the Queensland coast.

So, the question of why irukandji were being found off Fraser Island – and even further south – was still unknown.

“The short answer to that question is we have absolutely no idea,” Mr Seymour said.

“No one will fund any research to find out what is going on down there.

“Simple things like where the animals come from, how long do they live for, where are they found, when does the season start, when does the season end, are there different species down there?”

Mr Seymour said after the discovery of the jellyfish off the coast of Fraser Island 15 years ago, he and his team had raised the problem then and regularly since.

One of the big theories was climate change, with warmer ocean temperatures meaning the environment in which the animals could survive was potentially expanding.

But without data it was difficult to back up that theory, Mr Seymour said.

“You have virtually no way of keeping people safe down there apart from closing beaches.

“And I don’t see that coming, I don’t see tourism allowing that to happen.”

A Department of Environment and Science spokesman said marine stingers were a part of the natural marine ecosystem and the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service advised all visitors to take all hazards of the natural environment into account when visiting national parks.

“In particular, QPWS advises people that beaches at K‘gari (Fraser Island), Great Sandy National Park, are unpatrolled and people swim at these beaches at their own risk,” he said.

“Queenslanders are urged to remain alert during stinger season, which generally extends from November to the end of May.”