Expert reveals reducing mine deaths has not improved in ten years

Mackay woman Dawn Deakin had only just got home and there was a knock on the door. Suddenly her world would never be the same again. And now she’s fighting to see it doesn’t happen to others.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

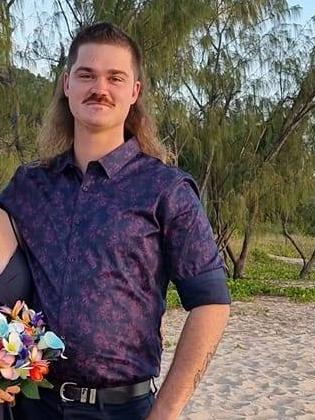

When Mackay woman Dawn Deakin looks back on the past 20 years of her life, one thing is consistently missing: her husband Trevor, who died from a tragic crash over a fateful Easter break.

Since that time, Ms Deakin has been involved in advocacy, and for her, risks for workers haven’t really improved.

UQ Professor of Occupational Health and Safety in Mining David Cliff said deaths linked to mining operations have been reduced by four since the 90s, but that level has remained consistent in the past 10 years.

On April 9 2004, Ms Deakin received the news that would change her entire life.

Trevor had been in an accident on his way back from Kestrel mine near Emerald, and he would never come home again.

“We were heading up to Townsville because our nephew was playing in the Foley Shield up there, and he was kind of doing his rush home to pick up his kids up,” Ms Deakin said adding that the incident had been unequivocally the result of fatigue.

“I’d only just got home. But then, the knock came and it was a male and female,” she said.

“And suddenly just, you know.

“After it kind of goes numb, you don’t really know what happened.”

Her and Trevor had met on a night of celebration at the Mackay Sugartown festival that marked the end of the crushing season.

Their respective siblings had competed against each other in the truck pull competition, and things went from there between her and Trevor at the Prince of Wales Hotel.

Mr Deakin had also once played for the Redcliffe Dolphins between 1979 and 1981.

Fatigue ‘rarely’ a contributing factor

Professor Cliff says statistics on incidents related to miners do not include deaths that happened outside of the mine sites.

“There are plenty of groups working trying to minimise the transit issues, but I think our statistics are not adequate,” he said about the Resources Health and Safety Department.

Mr Cliff took the example of the Peak Downs Highway between Mackay and Moranbah, acknowledging a lot of accidents happen on that road, with the most recent occurring only last month.

“But what proportion of that are of mine personnel and what proportion of those are because they are fatigued?” he said.

“It’s very hard to get statistics which give you evidence of how significant that factor is in crashes.”

This is despite Mackay Police Inspector Glen Cameron not being shy of mentioning tragic crashes in the region were often linked to “fatigue-related circumstances”.

‘No easy solution’

Professor Cliff said what remained a fact was that fatal incidents happen every year at mine sites and the trend does not change despite the industry discussing various risk management systems.

He explains that reducing risks for workers further does not involve identifying very obvious risks that have ‘one-off’ solutions, like increasing the use of automation so people don’t have to be on site in dangerous roles.

Rather, mine operations are now confronted to personal safety issues that have ‘no easy solutions’, and include psychosocial factors, such as mental health, fatigue management, work status, etc.

“I believe it can get to zero fatalities. I think we are in a situation where it has not improved because to manage those risks associated with the fatalities and serious injuries is complex,” Mr Cliff said.

“Production is always going to be a big driver of activity, the primary driver.

“So, the challenge is to ensure that is done safely, that people allocate enough time to do activities properly, they have the equipment to do things properly and they’re not penalised for doing things properly and taking more time.”

A parliamentary inquiry into coal mine safety held in 2022, had called out the culture of fear that dominates the industry, where people would be dismissed if they reported safety concerns.

“I’ve been in the mining industry for 35 years, and what I’m tired of seeing is new initiatives from the senior management, and then after, you know, a period of months, it dies down because the initial funding runs out and the workers go: “I’m not interested anymore,” professor Cliff said.

“I met many, many dedicated health and safety managers, and they really want to do their job, but on the other hand have limited resources, and they have competing commitments.

“But they need to be allowed to do their job properly.”

‘No one thinks it’s going to happen to them’

Ms Deakin got involved with the Road Accident Action Group after Trevor’s death, and has raised awareness on the dangers of driving for miners for the past 20 years.

She has gone from mine to mine, sharing her story with workers and managers and pleading for those who can’t wait to get home, that nothing should be pressing enough to risk their life.

“Something good has got to come out of a crappy situation,” Ms Deakin said about being involved in advocacy.

“And because they were my stepkids and I don’t have family here, it gave me something to focus on.”

We have asked Ms Deakin whether she has seen any improvements from the moment she had started advocating to today.

She said there would never be a way to completely avoid mine tragedies.

“The thing at the mines is that they always blame the shifts, the roster, the roads, they blame everyone else,” she said.

“But in the end, we can’t change that.

“People are people, if they don’t have to go on a bus, they won’t go on a bus, and there aren’t enough buses to do it.

“No one thinks it’s going to happen to them.”