Exercise Talisman Sabre sees thousands of soldiers help train army’s ready brigade

OUR finest soldiers, machinery and minds along with our American allies have been put to the ultimate test in the Queensland bush as they help our army’s on-call brigade be prepared for their next deployment.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

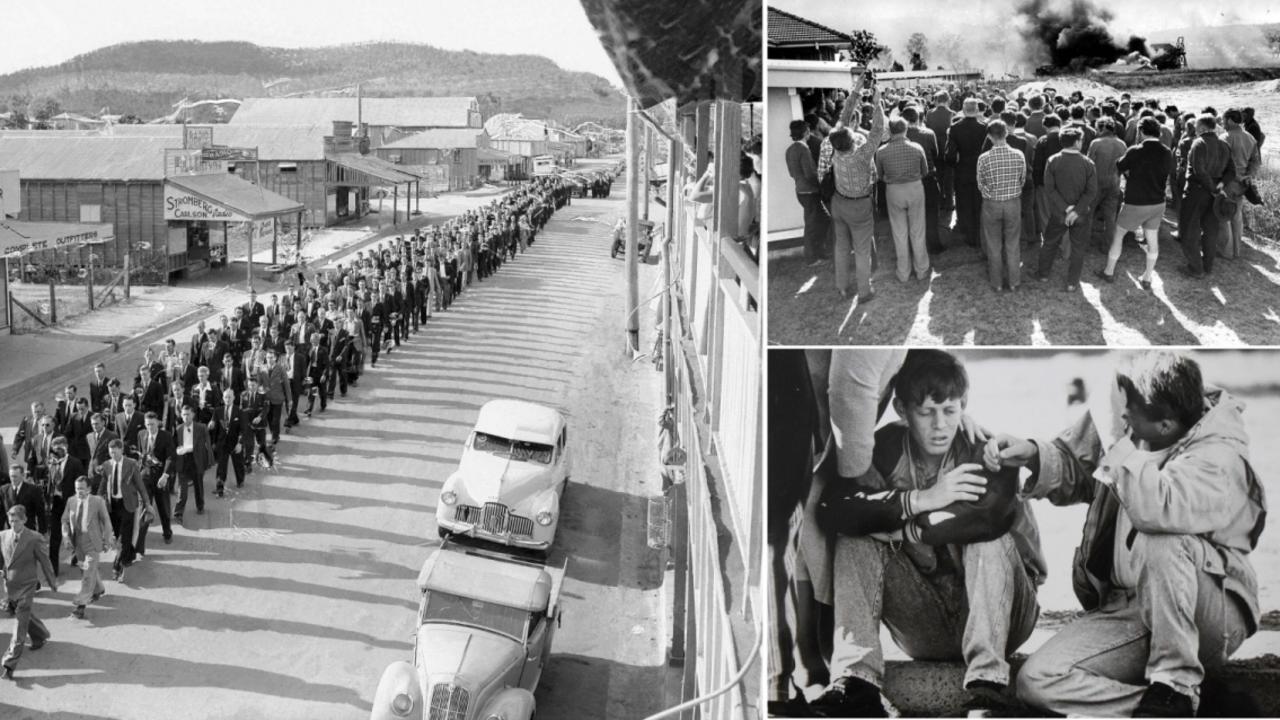

SNIPERS can lay waste to the best made plans. That was the lesson a young Australian Army machine-gunner learnt at 10.51am on Thursday as he waited for the final and largest assault of exercise Talisman Sabre at the Shoalwater Bay Training Area, near Rockhampton.

With just his shoulders and head peering above a 1.3m deep pit cut into a north-facing ridge near the centre of the army’s training area, the soldier had been peering out for days across a scrubby valley, searching for any movement that could indicate an attacking force was approaching.

To get there, he had stomped up to 40km through the bush, carrying more than 40kg in his webbing and pack, which he had been living out of for nearly three weeks. His mobile phone had been taken from him. He had been rained on but had not had a shower. And he had shivered in his sleeping bag at night as temperatures plunged into the single digits.

Then just as the snap snap snap and biritt birrit birrit of small-arms fire erupted across the ridge line, he was told that he was dead. A sniper lying concealed high up on the ridge that he had been watching for days had lined him up. The machine-gunner and his comrades from the Darwin-based 1st Engineer Regiment, which is part of the Australian Army’s 1st Brigade, had become the focal point of the final, massive assault of the exercise.

For about a week, their colleagues from Townsville’s 3rd Brigade had been manoeuvring about 2000 troops, tanks, armoured personnel carriers and artillery into position for the attack. Now at 10.51am, with Apache and Tiger attack helicopters providing aerial support, it was on. The sniper across the valley had timed his shots to coincide with the opening volley of the infantry after they had snuck undetected to within about 30m of the engineer’s position. An officer overseeing the training delivered the bad news.

“Five days of doing this shit and I don’t even get to fire a shot,” said the machine-gunner, looking wistfully at the hundreds of rounds of linked 5.56mm ammunition that he had carefully set up along the sand bags on the top of his pit, ready to feed into the F89 Minimi’s chamber before spitting out at the approaching forces.

The young soldier was forced to play dead while the blue force (the good guys in this training scenario) of the 3rd Brigade overran his regiment.

As he and another rifleman in the pit accepted their fates. They were obviously disappointed. But the 640-odd soldiers playing the enemy red force had known all along that they would ultimately get killed off.

Their real task had been to provide a realistic defence to help train their 3rd Brigade colleagues as they prepared to become the army’s ready brigade.

Under the army’s Plan Beersheba, which was released in 2011, the three regular force combat brigades were restructured into three roughly equal formations. Over a three-year period, the three brigades (1st based in Darwin and Adelaide, 3rd based in Townsville and 7th based in Brisbane) rotate through three different states of readiness: reset, readying and ready. The ready brigade would be the on-call brigade, able to be rapidly deployed to any hot spot or disaster zone around the world where the Australian Government wanted a presence.

This exercise, which has involved more than 30,000 personnel from Australia, the US, New Zealand, Canada and Japan, was the final test for the 3rd Brigade.

Brigadier Mick Ryan, the army’s director general of training and doctrine who had been heavily involved in planning the exercise for the past 12 months, said they had created a “a very complex and difficult training event” to test the soldiers.

“It’s designed to stretch them and show the Australian Government that they have a very capable and very ready land force that can go off and do the range of missions that they might need from their army,” he said.

Major Reg Dunthorne, officer commanding, A Company, 7th Battalion Royal Australian Regiment, was in charge of another red force defensive position on a hill to the south of the engineers. He explained that the red force had spent the longest period in the field during Talisman Sabre so they could create a “pattern of life” for the blue force to observe.

Over nearly three weeks, as the red force patrolled through Shoalwater Bay before ultimately digging in for their final defensive stand, they displayed habits and routines, which the blue force’s intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance elements could spy on. The intelligence would help the blue force commanders plan their final assault.

Maj Dunthorne pointed to the sky and said that US Gray Eagle and Shadow drones, with their telltale whining sound, had been hovering above them for two weeks. The drones, which The Sunday Mail was not allowed to photograph, were sending back high-quality pictures of the red force’s movements and positions to a central tactical command post.

The drones were based within Shoalwater Bay at Williamson Airfield, where the military had pulled together the largest rotary wing air battle group in the Australian Army’s peacetime history.

Under the command of an Australian officer, battle group Pegasus had 29 helicopters from Australia, the US and New Zealand lined along the edge of the field.

Major Keith Chambers, executive officer of the battle group, pointed down to the bottom end of the field where four US Apache attack helicopters were lined up next to 10 tactical troop transport helicopters from the Australian and New Zealand forces.

“See the awesomeness down there,” he said proudly.

Behind him were six Australian Tiger armed reconnaissance helicopters, six US Black Hawks and three HH-60 air ambulances from the US Army’s 25th Combat Aviation Brigade. The choppers had been constantly whirring in and out of the airfield, especially during the 10-day war-fighting stage of the exercise.

The attack helicopters had been simulating aerial assaults or providing protection for the more vulnerable transport helicopters. The air ambulances had been kept busy with a steady stream of what the military calls “no duff” missions, meaning the injuries were real.

US Army Chief Warrant Officer 2 Mick Albright was pilot in command of one of the medivac crews and said they were mostly transporting heat casualties but also patients with twisted ankles and limbs.

CW2 Albright said the US was the only major army that had dedicated medivac choppers. “We are solely life savers, that’s all we do,” he said.

He said the instant a soldier was shot, the clock started ticking on what they called the “golden hour”.

“After 16 years of armed conflict for the US, leaps and bounds have been made in terms of trauma care and the experts now have the idea of the golden hour,” he said.

“Just about nearly any person shot on the battlefield, their chance of survival is so much greater if they can be treated within that first one hour – the golden hour,” he said.

The desire to reach patients however is tempered by the reality that wherever he or she is lying is probably under an intense assault.

“The nature of this is that we never launch until something has gone wrong,” he said.

“There’s always smoke involved and there’s always bullets involved, if everything had gone to plan nobody would call us.”

The Australian element was ecstatic at how the troubled MRH-90 Taipan helicopters had performed. The Taipans were bought for $4 billion to replace the army’s ageing fleet of Black Hawks, however they had suffered numerous technical and mechanical issues over the past decade.

Major Jason Long, officer commanding of the 5th Aviation Regiment’s Technical Support Squadron in Townsville, said the Taipans had “hit a sweet spot” on this exercise.

“The MRH has turned a huge corner and we’re really starting to realise the potential of what they can bring to the Australian Army,” he said.

“It’s proven that the MRH has capabilities above what the Black Hawk can provide.”

One of their big tests had been a night-flying mission.

“We had four MRHs on the HMAS Canberra which was 230km off the coast, they flew a mission and inserted a pre-landing squad undetected and returned to the ship at night,” he said. “The Black Hawks do not have that range and would have struggled to return to the ship.”

As he was talking, four Taipans took off simultaneously with two US Apache attack helicopters to collect blue force troops in the field and insert them closer to their final objective.

Maj Long watched on before pointing towards an army truck on the side of the airstrip. The regiment’s three most senior non-commissioned officers were watching the helicopters take off.

“For all of them to come out and watch that, it must be pretty special,” he said.

From the exercise control post within Shoalwater Bay, Major General Gus McLachlan, commander Forces Command, could watch everything from the drone footage – the movement of the troops in the field in real time on the army’s newly integrated technology platform.

“On this exercise two or three years ago you would have seen a watch keeper, a battle captain, with five different systems in front of them and they’d have to be taking information from one and what we call fat fingering it from one system across onto another one,” he said.

“Of course that introduces the risk of error and introduces time differences and so on. We’ve really emerged at a point now where we’re starting to see the technology fuse into a coherent picture and that’s where we’re going to get our advantage from as an Australian defence force.”

However Maj-Gen McLachlan said the exercise had also provided a timely reminder that even the greatest technology “will never give us all the answers”.

“Despite all the best surveillance technology, military forces will still have to reach out and actually fight for information to achieve certain things and that’s why vehicles and tanks remain important,” he said.

“Sometimes bad guys get to choose where that fight starts and you want to be there with some considerable combat power to survive that first hit. After that you can start to manoeuvre and start to be clever.”

As the thousands of troops and equipment start crossing the country back to their bases this weekend, commanders have already begun reviewing the lessons learnt at Talisman Sabre and planning for next year when the 3rd Brigade will return to the field as the enemy forces to help Brisbane’s 7th Brigade complete their training to become the army’s go-to force.