Escape from death led to new life down under for Peter Baruch

A Gold Coast man’s family fled as the Nazis brought terror to Poland - a decision that saved their lives.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

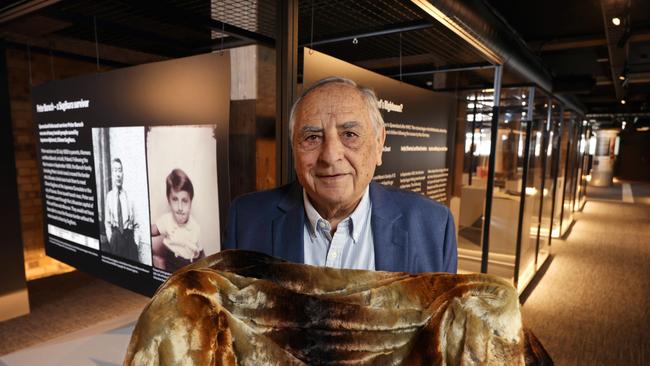

Holocaust survivor Peter Baruch owes his life to a virtuous Japanese diplomat, a “plush” blanket and his parents’ unflinching determination to escape Nazi-occupied Poland and give their son a new life thousands of kilometres away from war-ravaged Europe.

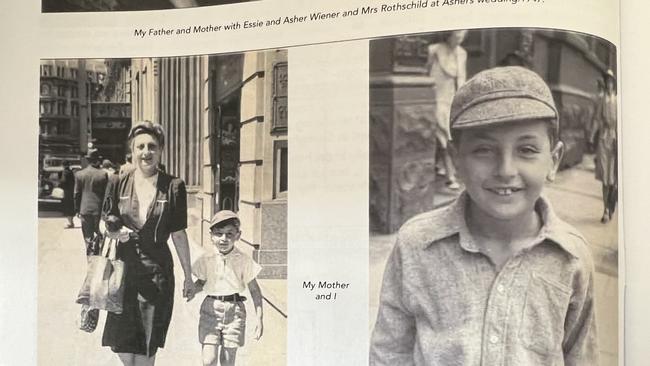

Mr Baruch’s story begins in Lodz, Poland, on July 23, 1938, when he was born. It crosses Lithuania, Russia, Japan, China, Indonesia Australia and New Zealand, and continues today in the life of this genial 85-year-old Gold Coast father of five and grandfather of seven.

Mr Baruch’s story is one that Jason Steinberg, chair of the Queensland Holocaust Museum and Education Centre, believes has perhaps more resonance today than it has had in the eight decades since World War II’s end. With antisemitism on the rise across the nation, the QHMEC’s job of educating Queenslanders on the horrors that can so rapidly unfold when a people are held collectively responsible for a nation’s ills has never been more important.

As Mr Steinberg said earlier this year: “As a proud Queenslander of Jewish faith, I have seen how quickly since the barbaric Hamas terrorist attacks on October 7 last year that people have descended into fanaticism in their unrelenting vilification of Israel, Jews and anyone who supports Israel’s right to exist.”

The QHMEC has just marked its first birthday and has not only attracted thousands of visitors since then Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk formally opened it on June 30 last year.

The museum in Central Brisbane has also won both gold and silver prizes in the Eventex Awards, which honour creativity and excellence in the global world of events and experiential marketing.

Mr Baruch, whose life story will soon be a major exhibit at the QHMEC, speaks regularly about his experience to educate a rising generation about the horrors flowing out of racism and bigotry.

He was born into wealth in Poland in 1938, with his extended family involved in the textile trade dating back into the 19th Century when his grandfather opened one of the original factories in Lodz.

In 1939, a week after the Nazis had crossed the Polish border, sparking World War II, Mr Baruch’s mum and dad went against the consensus of the wider family (many of whom believed the Germans were a civilised people who would not cause serious harm to Jews) and decided to get out.

His mother wrapped her baby in a blanket to keep him both warm and hidden. It had been made in his family’s factory, marketed as “plush”, and he still has it.

The family took off in a small car under the cover of darkness, headed for Kaunus Lithuania, where it was believed they could get a visa from the Japanese Embassy to transit through Japan to a safe country.

The diplomat who approved that visa did so illegally. His name was Chiune Sugihara and he risked his own life by disobeying orders from the home office and signing off on around 6000 escape visas for Polish Jewish refugees.

“He had asked permission (to issue visas) at the start of 1940 and finally, in June of 1940, he took it upon himself to follow his conscience, defy his government and start issuing transit visas with the help of his staff,” Mr Baruch says.

Over a period of two or three weeks, Sugihara saved the lives of more than 6000 people.

As Mr Baruch points out, Sugihara’s bravery, which was honoured by Israel in 1985 as “Righteous Among the Nations”, has resulted in around 200,000 human beings being granted the gift of life over the past 80 years.

“There are obviously very few of the original people who received those visas left,” he says.

“But you look at their children, their grandchildren and their great grandchildren scattered across the world, and you see 200,000 people, and that number is growing.”

The family still had a long journey to get to Japan and their possessions were plundered by Russian troops, who even took away their car.

But the trio eventually made it across the globe to NZ, where both Mr Baruch’s mother and father, though physically depleted by the trauma, created a successful business in textiles and fashion, his mother employing up to 50 women and becoming one of the first in NZ to go to Europe to bring back the latest trends.

Mr Baruch took over the business in the 1960s after both his mother and father died long before they reached old age.

“I know they died early because of what happened in Poland and what they endured during those two years of crisis crossing the world,” he says.

The rest of the family who remained behind in Poland, including his father’s seven brothers and their entire families, were all killed by the Nazis.

As for Mr Baruch: “In 1990, with my children all grown and some going off to Europe, I made the decision to live where I wanted to live, and that was the Gold Coast.”

He lives in his Gold Coast apartment happily, gratefully.

A book – “The Ninth Candle” – records his extraordinary life.

But Mr Baruch also believes it vital he continue to tell his story, especially to those who don’t understand how civilisation’s thin veil can be so rapidly torn aside to reveal the horrors beneath.