Edited extract from mining magnate Ken Talbot’s biography

In this edited extract from the biography Rum & Coal, late billionaire Ken Talbot’s own notes reveal what drew him to agree to scandalous payments to Gordon Nuttall.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Probably the hardest point to defend was how on earth anyone could have gone from slandering Ken in parliament, to being so close a friend that he would be lent $300,000 without any discussion about ever getting it back again – based upon perhaps only four meetings in the meantime?

Those very first hearings before the Star Chamber had shown how clearly the CMC was focusing on this issue, both in their questions to Ken and to Gordon Nuttall.

This one was much harder to answer. Don Nissen had a go. “If I was a psychologist, I’d say Ken’s humble beginnings gave him something of an inferiority complex,” he said. “He almost presumed that Gordon Nuttall was smarter than him, whereas he never was. If Ken was invited up to Government House, as we were every year, he’d skite about it – to have those awful sandwiches and cheap cask wine. He almost considered it an honour for Gordon Nuttall to have asked him for money.”

Clearly, that whole psychological question of wanting to be liked, and to matter enough to be

significant, would be explored in court. But they would need to do better than that. And so huge swathes of Ken’s legal statement are given over to the concept of what he called mateship, and how Ken thought of a friendship. Early in his statement, Ken said: “At the time when I agreed to assist, I was speaking to a different Gordon Nuttall to the one most people would identify with in 2010, namely, a disgraced former politician packed off to jail for corruption,” the statement said.

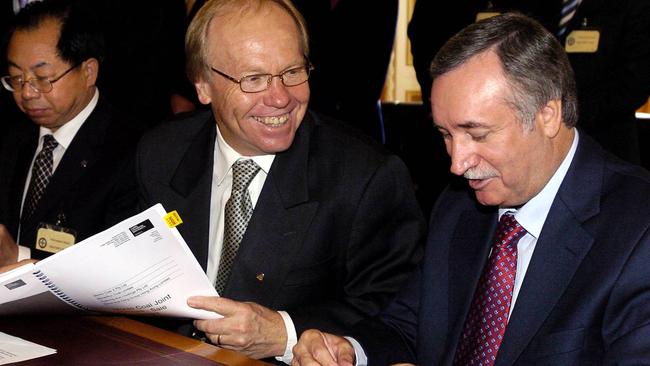

It then went back to 2002, when Nuttall was in his first term as a junior minister, but apparently looking to a future in the private sector. The next few lines were quite telling about what Ken might ever have seen in him. “He was from a State School background like me, very much self-made, hard-working and an espouser of the importance of family. He had no real airs or graces, he was a knockabout person, fun and likeable. In short, he just seemed like a good bloke to me.”

“I certainly liked him, and of that there can be no doubt,” the statement continued. It mentioned the “vile spray” Nuttall sent in his direction in 1998, but said it had later been confirmed that Nuttall had been put up to it, and that Ken had moved on before they first met at a luncheon on 20 July 2001. At that lunch, Nuttall sought Ken out: “And was man enough to apologise to me. He wanted to right that wrong, and that impressed me enormously. He wanted to be mates. His profound apology – along with several rum and cokes – went a long way to fasttracking that process.”

It’s clear what was happening here. This statement wasn’t just about Gordon Nuttall. It was also very much about Ken. That whole page was really about establishing Ken’s character: ordinary man, a mate, one of the people. When Ken applauded Nuttall by saying he had no airs and graces and was knockabout, fun and likeable, he’s not just saying that’s how Nuttall is. He’s saying that’s how he sees himself, and wants everybody else to see him.

The statement goes on to say Ken thought Nuttall: “A popular guy, and all sorts of people from the Premier down seemed to be of the same view. I thought we would become firm friends.” He went on to say that Nuttall told him on 4 June 2002 that he, Nuttall, planned to leave politics in “a couple of years”, and that “he was the sort of person I could well envisage coming across to work with me – like so many from the government side of the fence who had done that with me before.”

“If you had asked me back then whether I knew Gordon, I would have told you we were mates.”

All this build-up is explained by the section that followed, describing what Ken thought of as a distinct category of finance, namely the “mate’s loan”.

He did, though, note that there were two elements that brought it back out of that category again.

He was careful not to present Nuttall as “one of my best mates”, since that would clearly have been impossible to demonstrate, and instead called it an “emerging friendship.” Secondly, he said, the loan was not for Gordon Nuttall himself.

The statement said that as far as Ken was concerned, the sole purpose of the payments was to assist Gordon in securing the financial future of his children.

The statement then quoted CMC Financial Analyst Karel Weimar in her calculation that only 39 per cent of the funds Ken supplied were ever used for the benefit of his children, and that the children later fully reimbursed him anyway.

This was an important section, as it sought to distance Ken’s good intentions from Nuttall’s

indiscretion. The next four paragraphs are worth quoting in full.

“I have no way of knowing whether, at the time Gordon asked for assistance, he intended to

disburse the money contrary to the purpose he expressed to me.

However, if that was his intention, and I had discovered that at the time, I would not have given him one cent. Furthermore, it is likely that I would have taken steps to bring that deception to the attention of the Premier of the day, Peter Beattie, if not the authorities.

“At no stage did I think that my agreement to assist Gordon’s children had anything at all to do with my business. What I agreed to do was on a completely different – personal – level. I was not dealing with Gordon the Minister, I was dealing with a guy I had got to know and like, a father who needed a hand to set his children up.

“Nor did I have any inkling that Gordon was attempting to extort me or was tacitly offering to favour me in some way in my future dealings with the government. Such a scenario would have been the easiest thing in the world for me to deal with – I would have shown him the door and immediately either telephoned Peter Beattie or taken Keith De Lacy with me to see Beattie.”

At the end of this introductory section, Ken had written, by hand: “42 Yrs experience. No history of corruption.”

• • •

Later on, he gets on to mateship, in such detail that he might have been drafting a PhD on the subject. Here’s a taste: “The concept of mateship is wonderfully Australian, and perhaps uniquely so. But you can’t go down in the pits during a nightshift and not come back up appreciating the value of mates. So having and being around mates has always been a big part of my life.

“I have over the years been lucky enough to have mates across all walks of life and both men and women. Some I would not see for years and then, when we run into each other, it feels like it was only yesterday that we last saw each other. I have mates who visit me at home regularly and I have mates who have never been there.

“Most of the people who work with me are mates, but that doesn’t mean we live in each other’s pockets and, with some of them, we probably wouldn’t stay mates for very long if we did.

“I have had mates to whom I have confided the most personal things and mates who I just enjoyed having a beer with. So some mates are of course closer to you than other mates, but they are all mates just the same. Some mates let you down from time to time and others are like rocks.”

And then, what this has all been leading to: “I became, and remain I hope, mates with quite a number of politicians – on both sides of the political divide. I enjoyed their company and felt comfortable around them. I would, for example, call both Peter Beattie and Terry Mackenroth mates. On the other side, guys like Rob Borbidge and Mike Horan are mates. So there is a wide spectrum and I make no attempt to rank them in order of priority, or by reference to how many know the names of each of my children, have met my wife or have been to my house. You don’t do that to your mates. I hoped Gordon and I would become firm friends – good mates. If you had asked me back then whether I knew Gordon, I would have told you we were mates.”

Beyond that, there are a few other stabs at explaining it all. He had known Gordon Nuttall 10-and-a-half months before the meeting at which Nuttall requested money; he pointed out that Wayne Bennett became one of his closest friends in the world within a similar period of time. The same was true of Don Nissen. The prosecution would doubtless have pointed out, though, that he spent a hell of a lot more time with those two than he had with Nuttall.

• • •

There was a broader philosophical question Ken wanted to address. Every time he made a political donation, turned up at a pay-per-seat fundraiser or anything like it, wasn’t he, in some sense, expecting something favourable from the transaction?

How about when he was approached by the fundraising committee of the Queensland Library for donations? Neil Roberts, the Chair of the committee and the former Chairman of the Bank of Queensland, and David Little, former Managing Director of the Brisbane-based construction engineering company Watpac, sought a contribution for the Treasures Wall of the Library project.

“Both Neil and David informed me that they reported directly to Anna Bligh, who was the Minister for Education at that time, but they are also happy to tell me that she was earmarked as the future Premier,” Ken wrote.

Ken donated $500,000 to the project, and the two men: “Advised me that they would inform Anna Bligh positively of my contribution.” So, what did that mean? Did it mean that his money would buy access to the Premier? “In my mind,” Ken wrote, “there was always the issue of a favour and disfavour type concept.”

• • •

For his part, Ken told those around him he was confident. Amanda said they never once discussed the possibility of him going to jail. “It was just a mess from a business point of view,” she said. “But home kept on ticking along, and I had his back and supported him. It didn’t put any strain on our marriage or anything. He had the funds to fight it and he was determined to fight it.”

Privately, though, Amanda was deeply concerned. “I was very worried about Ken being found guilty and going to jail,” she recalled. “I thought about it all the time, but never let on to Ken I was worried because then he would worry that I was worried. I wanted to be strong for him and be positive that all would be well in the end.”

After the allegations were made against him, Ken would ask Amanda: “Darling, are you proud of me?” Amanda added, “He always asked jokingly, but I think he wanted reassurance that I wasn’t disappointed in him.”

She wasn’t. She thought he’d done a dumb thing, but knew that was the man she married, generous and – those words again – a soft touch. She never told him it was a dumb thing to do. No need. He already knew it.

This is an edited extract from Rum & Coal, an upcoming biography of Ken Talbot, written by Chris Wright and published by Calvi Publishing.