Dying with dignity, compassion and peacefulness is something we all deserve

After I watched my little brother take his last breath, through my tears I saw clearly that those final painful hours of his life were not needed, writes Peter Gleeson.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fighting like a tiger, his breathing had become increasingly laboured and torturous and as the inevitability of death edged closer, the final exhalation was a relief. The raspy sound that had punctuated the air for the past few hours was eerily and suddenly replaced by dead silence.

An instinctive and precious final kiss on the forehead triggered salty, gut-wrenching, uninhibited tears.

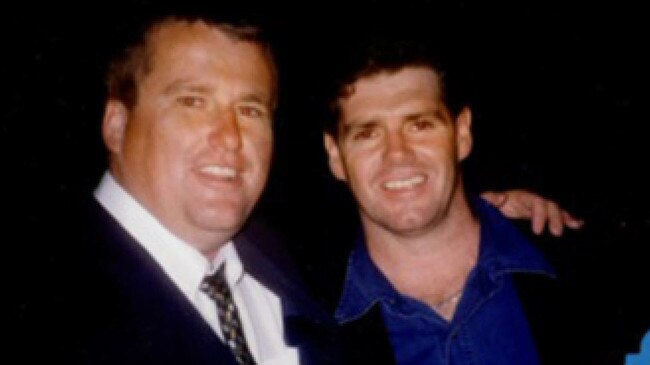

I had just watched my younger and only brother, Daryl John Gleeson, 53, die.

On June 9, he slipped away from us after a 15-month battle with a disease known as Myelodysplastic syndrome, which is like leukemia.

His only chance was a bone-marrow transplant, but alas, it didn’t happen.

WHEN THE SPIRIT GOES

Today, it is important to not only remember what made him an endearing and wonderful larrikin, but pose the vexed question that surely troubles anybody who has witnessed a loved one die – were those final hours truly necessary?

The answer is no. Resoundingly. When the spirit is gone, when the body has had enough, surely dignity and compassion in death is as important as it is in life.

As much as the struggle and battle for life is real and cherished, does anybody really want to see the pain and anguish of those final hours when there is nothing – only mental scarring – to be gained?

Being bedside in those final months, weeks and days with Daryl, or Albert as he was affectionately known, was the most difficult – yet most important – responsibility imaginable for a brother. He deserved nothing less.

Daryl was buried in the northern NSW town of Grafton, with 500 people attending a ceremony at his spiritual home, the Clarence River Jockey Club.

In this age of Covid-19, we were blessed to celebrate his life with such a big crowd and no restrictions.

But the grief is commensurate with the love, and while his final days were uplifting, sad and confronting, he did get to see many of his mates, who knew he had little time left.

Daryl and I never really talked about the possibility he may die from MDS.

He knew it was serious and he tried everything to overcome the odds. It was as though we fervently believed he would make it and to talk negatively would put the “mock’’ on any chances of recovery. His specialist, Dr David Rabbolini, had told me when he was first diagnosed that this was a “nasty’’ disease, and he would be “walking a tightrope’’ during treatment.

Still, as he endured test after test earlier in the year to qualify for a bone-marrow transplant, we never spoke of the possibility that he would not survive. Like the true punter he was, he knew 100-1 shots could get up. It was rare but where there was life, there was hope.

In those last few days, after his left leg had been amputated below the knee as an infection began to ravage his body, ever so slightly he let down his guard. He had endured 55 blood and platelet transfusions in the previous five weeks and he had simply run out of tarmac. He was being kept alive but infection and internal bleeding were now overtaking his body.

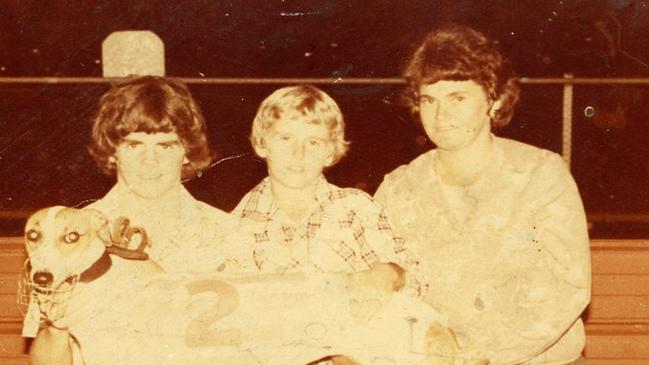

“I’m off the menu, Scoop (my nickname), aren’t I?,’’ he said as we waited for him to be returned to the Purple Room at the Grafton hospital, the palliative care unit, after he’d been home with mother Maxine and stepdad George Ward for the day. On one of those final few days at home – he’d go back to the hospital in the evening – we counted 22 cars out the front, people coming to see him. He was tired. He slept a lot. But when he woke he’d be animated, reminiscing about good times with his mates. Whether it was his beloved Grafton Ghosts winning the competition or a favourite greyhound winning a big race. These were important hours.

DARYL’S DYING WISH

A few days before he left us, we’d taken him to the new Grafton greyhound track, a $5m facility which he had seen built over the previous six months. His dying wish was to be at the big Grafton meeting last Wednesday night where the main sprinters cup was renamed in his honour. Make no mistake, he was there.

It’s said that grief is commensurate to the love accumulated for a person and, to be sure, Daryl was much-loved. The day he was born, August 21, 1967, Dad “Chicka’’ Gleeson took me to Port Kembla Hospital to see him.

As we peered through the window, there he was, and my Dad, a wharfie, said: “Whaddya think?”

“He’s a beauty, Dad,’’ I said.

Little did we know how prescient those words would be. The outpouring of grief for him at his funeral, people from all walks of life, many from the thoroughbred and greyhound racing industries and footballers galore, was testament to his measure as a man.

He never gave up

Daryl was a big bloke, loved a beer and a punt. In those final few months, he became a shadow of his former self. Not mentally, but physically. Yet he never gave up. He never complained. He got on with it, trying to do rehab because he knew that was important. Daryl was as sharp as a tack right up until those final hours. He was a mathematical genius, one of the great “pencillers’’ on a racetrack.

The thing about losing your only sibling is that it’s a hole in your heart that hits you like a ton of bricks. We grew up in a housing commission place in Mount Warrigal, south of Wollongong, roaming the streets after school and at weekends on our bikes, always home before the lights went out.

It was a simple, wonderful childhood. We played footy in winter, cricket in summer and golf at Port Kembla.

Holidays were always in Grafton, catching garfish with our grandfather Taffy and our grandmother Irene making pancakes and fritters on the wood-fired stove and cooking the fish.

Even as my work took me away to other cities, other states, that link with Albert was never broken. We’d chat almost daily.

BEARING THE GRIEF

So what is grief? It is an outpouring set in motion by love. While it is painful to bear, we are richer for it. The reason the mourners shed so many tears for Albert was the corroboration between love and grief. The greater the love, the stronger the grief. In this crazy ‘woke’ world of political correctness, Albert wanted none of that. He scorned authority. He wanted the simple life and it was a lesson for us all.

On this journey, Albert was my brother, but he was also my best friend. We grew together, we matured together. We celebrated together, commiserated together. In that sense, he will always be with me.

My 9-year-old son was at the funeral and amid all the emotion and grief, he remained stoic until the cemetery service.

There, he cried his little heart out.

I asked him what he’d taken away from the number of people at the funeral and the way we remembered his uncle.

As only an innocent 9-year-old could say it, he said: “Uncle Albert was a good boy. People loved him, Dad.’’

And so, despite Daryl’s lack of political appreciation, the irony of this piece is that it must trigger debate and action on changing legislation to reflect modern, progressive euthanasia. Australia must unify and reform its Voluntary Assisted Dying (VAD) laws. Let me make it clear, I am pro-life, anti-abortion. I think killing a healthy unborn child right up until 38 weeks is barbaric, although I support a woman having the right to abort in circumstances such as rape or fetal deficiency.

But the laws around death and the way we say farewell to our loved ones must be more humane. Voluntary assisted dying laws are now legal in Victoria, Western Australia and will soon be enacted in Tasmania. Queensland will soon vote on the issue.

A day or so before Albert died, he had run his race. For a mad horse racing punter, in his parlance, he was behind the ambulance and under the stick. Twenty-four hours before he passed, I have no doubt he would have gladly went to the betting house in the sky, Godbet, demanding an odds boost from the man upstairs.

THE LAST DAY

That last day added nothing to my brother’s life. It’s an oft-quoted saying, but you don’t know what you don’t know. This is particularly true of euthanasia and what it means. It was the first time I’d endured somebody close to me dying before my eyes. Until you do, the debate can be nebulous. When it’s real and unfolding before you, it gets your attention.

When the issue, or even option, of euthanasia comes knocking, as surely it will, be prepared for a life-changing experience. This is not in any way a pro-life debate. It has nothing to do with life. It’s about death and dying with dignity, compassion and peacefulness. It’s about average Aussie mums and dads being able to reach a consensus that the loved one they are watching die needs to go – and go now, not in 24 or 48 hours.

WHAT IS RIGHT

It is also important that the dying person, when of sound mind, supported a voluntary assisted dying intervention.

With the right advice from medical practitioners, with the proper ethicist training, these are not difficult decisions when the time comes. There will be those that argue that we should never be playing God, or that we should never be ceding more power to the state.

These are the risks we take for a better, more progressive society. Our final journey should be remembered for all the right reasons. Put the medical and ethical checks and balances in place and make sure it’s a consensus among the key decision-makers.

Surely, the greatest gift of love is not what we do for somebody in life, but what we do for them as the final curtain comes down. Love comes in many different guises. The act of sending a loved one to a better place, rather than enduring the final, frenetic, chaotic, challenging, painful hours as death nears, is surely the greatest gift of all.

As his life ebbed away in those final minutes, Daryl knew what impact he’d had. Was he ready? I don’t know and I will never know, because he loved life and life loved him. But he faced his moment of truth with courage, conviction and a strength that was simply extraordinary.