Secret premiere for a Premier: Copy of Fitzgerald Inquiry report ‘fell off the back of a truck’

On the eve of the release of the Fitzgerald Inquiry report, the state’s corruption busters were forced to operate under a veil of secrecy and conduct clandestine meetings – not even Premier Ahern was privy to an advance copy. But one did mysteriously appear.

Crime & Justice

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime & Justice. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ON the evening of Sunday, July 2, 1989, then Queensland premier Mike Ahern set up a confidential meeting at his father Jack’s house in Caloundra on the eve of the historic release of the Fitzgerald Inquiry’s official report.

Present at the meeting were Deputy Premier Bill Gunn, former Attorney-General Neville Harper and the National Party member for Roma, Russell Cooper.

After two long years, hundreds of witnesses and many thousands of pages of transcript generated by the corruption inquiry, commissioner Tony Fitzgerald was set to formally hand over his report to Ahern the next morning in the office of the premier in the Executive Building in George Street.

Fortitude Valley site linked to Qld’s Fitzgerald Inquiry sells after bidding frenzy

Opinion: Courier-Mail’s role in Fitzgerald inquiry must not be overlooked

The 630-page report had been prepared under extreme security. Not even Premier Ahern was privy to an advance copy.

He and his minders wondered how the Premier could discuss with any understanding and clarity the content of the report, and then discuss it with the media and Cabinet on Monday, July 3, if he had not been able to read it beforehand?

Mysteriously, a copy found its way into Ahern’s hands on the Sunday, and the clandestine meeting in Caloundra was to prepare the government’s response to the wide-ranging, epochal Fitzgerald report. There were no public servants present at the meeting.

“My advance copy of the report fell off the back of a truck,” says Ahern, 77.

“A confidential source understood that I needed to be able to speak coherently about it to my Cabinet, the press and the public. There you have it. It was secret squirrel.

“At that meeting in Caloundra we discussed what our response should be after something as dramatic as this, this corruption that had entered the business of government. We had to deal with it. It just had to be done.”

Just before 9am on the Monday, journalists crowded into the Walter Burnett Building at the Ekka Showgrounds site in Bowen Hills. It was a budget-style lockup. No stories were to be filed until 2pm, when the Fitzgerald Report was officially released.

The Courier-Mail writer Mike O’Connor observed: “If the city seems somewhat quieter as you travel to work today, it will probably be because a good number of folk around town are holding their breath until 2pm … when journalists … will be permitted to start filing stories.”

Another writer for The Courier-Mail, Don Petersen, described colourful scenes on the ground despite what he said was a “predictable … blueprint for political, judicial, law-enforcement and even electoral reform”.

“For about an hour before yesterday’s release of the report on the most massive corruption inquiry in Queensland’s history, police dogs checked out Brisbane’s RNA showgrounds … the dogs were a precaution against the possibility of a bomb in the Walter Burnett building, where about 400 reporters were to be locked up for the preview of the Fitzgerald Report,” he wrote.

Before 10am, Ahern personally received his bound copy of the report from Fitzgerald in his office in George St. Deputy Premier Bill Gunn was also present. Some weeks earlier Ahern had bravely announced that he and his government would implement the report’s recommendations “lock, stock and barrel”.

Ahern then attended the usual Monday meeting of Cabinet and said to his colleagues, in relation to the report: “Who’s going to stand up and say we’re not going to do anything about this?”

He said it was time to act immediately towards the process of reform in Queensland.

In the lead up to the report’s publication and release, unprecedented security was in play. It was printed at the office of the government printer – GoPrint – based in Vulture St, Woolloongabba. The building was guarded both inside and out.

“Once we took the copy in there was 24-hour security around the building,” recalled one employee. “Each night, when they finished working on the report, it was locked in the safe under the supervision of officers from the Criminal Justice Commission.”

Fitzgerald inquiry: Where are key figures now?

Fitzgerald Inquiry Queensland: Last laugh on bent cops who ran ‘The Joke’

On that day 30 years ago, members of the public queued outside the GoPrint office, waiting to buy a copy. It retailed for $20. It’s first print run was 2,000 copies.

“Fitzgerald was very jumpy in the lead up to the report’s release,” remembers Ahern.

“It had to be properly embargoed in the interests of fairness. This was all very dramatic for Queensland. Nothing like this had been done before.

“It was going to generate a change of culture, of leadership, the way we did things.”

Twelve days after the release of the report, more than 5,000 people staged a “democracy rally” on George St before spilling into the Roma St forum. They carried placards. One read: “THE FITZ REPORT IS DEMOCRACY; PEOPLE FIRST; RELEASE DOCUMENTS.”

And 18 days after the report entered the public domain, a letter was hand-delivered to 12 Garfield Drive, Bardon, the home of sacked police commissioner Terence Lewis in Brisbane’s inner-west, from the office of the Special Prosecutor.

It informed Lewis that two summons’ would soon be issued to him, charging him with 16 corruption offences and two of perjury.

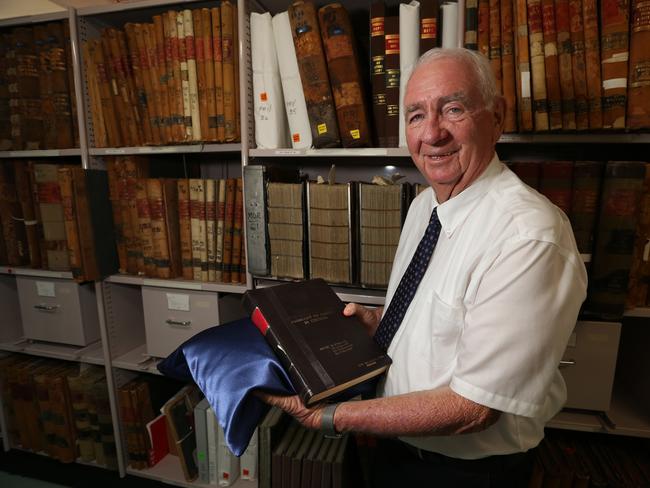

In May last year Ahern donated his famous copy of the Fitzgerald Report to Queensland State Archives.

He had it on a shelf at home in Caloundra for almost three decades, and often referred to it for research or to refresh his memory on that incredible period in the State’s history.

Today, Ahern will have little time for reflection. He will be undergoing physiotherapy in Buderim, on the Sunshine Coast, after a recent right kneecap and joint replacement.

“It was mine to do,” he says of the moment Tony Fitzgerald, QC, handed him that copy of the report that changed Queensland.

Would he ever reveal the name of the source who managed to secure him an advance copy of the report?

“No,” he says.