WHEN Tiahleigh Palmer’s body was eventually found on the muddy banks of the Pimpama River, investigators had little else to go on, writes Kate Kyriacou in the second part of our investigation into the Logan schoolgirl’s horrific murder.

SHE was stripped to her torn underpants, decomposing on the banks of the Pimpama River. A little girl, her body dumped half in, half out of the water.

Later, they’d find her shoes as police divers arrived to search for any further evidence.

She was found by some fishermen, an exercise in relaxation turning to horror.

And imagine being the police, the first on scene, the forensic specialists who arrived after.

The ones who photographed her, who wrapped her up and took her away.

The terrible state she would have been in.

Or those whose job it was to knock on Cindy’s door, to tell her that her daughter wasn’t coming home, that her body was dumped in the mud, left to rot, left to the elements.

Or those who sat with the Thorburn family, who offered sympathy to the people who deserved none.

If they’d had any doubt, police now knew they were looking at a murder.

The funeral for Tiahleigh Alyssa Rose Palmer was held on November 15, a sea of purple T-shirts – the schoolgirl’s favourite colour. White roses were placed on her white coffin.

White balloons were released into the sky as Maori men performed the Haka.

Mourners heard about a girl who loved to dance and shop. A happy, bubbly girl.

Cindy, distraught, collapsed over her daughter’s coffin.

And when it was over, Rick Thorburn took his place among the pallbearers. Crocodile tears in his eyes. A silver handle grasped in his hand. He carried the little girl he’d smothered to a waiting hearse.

STRANGER abductions in Australia are incredibly rare. Children, sadly, are much more likely to be murdered by their parents.

Police had to consider that this was another Daniel Morcombe, that perhaps in the moments after her foster father apparently watched her walk towards the school gate, something had happened to her. After all, it had taken Brett Cowan less than 90 seconds to lure Daniel from a public space in broad daylight.

In any murder investigation, those closest to the victim are considered “persons of interest” as a matter of course. They are looked at, in the most part, so police can rule them out, so they know where to focus their investigation.

This would certainly have been the case with Tiahleigh’s mother, Cindy and her partner, her biological father, Andrew, who had not seen his daughter for five years, and her foster family.

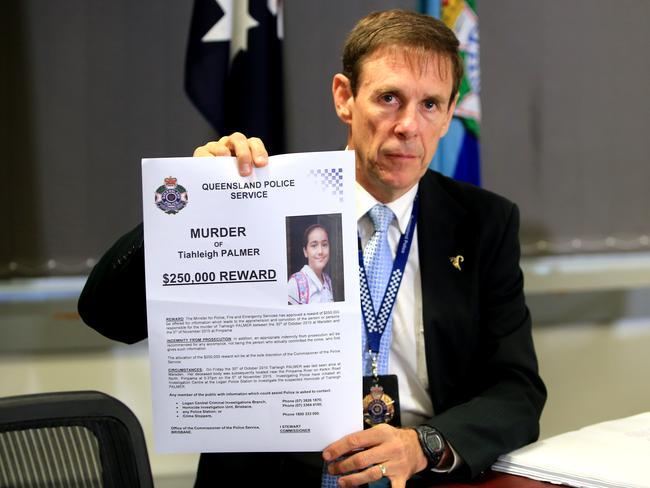

Detective Superintendent Dave Hutchinson, the face of the investigation, would front media often in the months that followed the discovery of Tia’s body.

Police faced heavy criticism in those first weeks. Why had it taken six days to alert the public to her disappearance? Had police taken her disappearance seriously or did they dismiss her as a runaway?

Police questioned Tia’s friends. Had she talked about skipping school that day? Had she been planning to meet someone?

They pulled footage from CCTV cameras in the area. They pleaded with people to come forward if they’d driven by the school while recording on a dashboard camera.

The response to their request for footage was overwhelming. Trawling the footage for any sign of the schoolgirl would use considerable resources.

The response from Tia’s fellow students was less overwhelming. Most of them refused to have anything to do with police.

“We … have a little bit of a concern that maybe some of the students know a little bit more than what they’re telling us and they’re a little bit concerned that what they tell us might get them into trouble for some minor reason,” Det Hutchinson said. “If there’s any issues in relation to wagging school, or things like that, they’re not going to be in trouble.”

He went as far as to plead with parents to encourage their children to co-operate with police. The children were the ones, he said, who likely had the information that would help police solve this case.

At those early press conferences he was asked whether any independent witnesses had seen Tia get out of her foster father’s car.

No, he’d replied. They were yet to find anyone who’d definitely spotted her.

So how do you know, a reporter asked, she was actually taken to school?

“The main people that are associated with Tia, we’re comfortable … that we’ve made the inquiries and everything seems OK,” Det Hutchinson said.

Soon, information was coming in from the children. And while it was well-meaning, it would throw the entire investigation off course.

One girl said she saw Tia that morning. She told police she knew it was that day because someone in her family had had a birthday on the same day. She’d even spoken to her.

“Now, the information we have at this stage is she’s been dropped off at school about ten past eight that morning,” Det Hutchinson said.

“She was dropped off a little further down Chambers Flat Rd, outside the primary school, and that she’s walked up towards the school. Really, as it stands at the moment, that’s the last positive sighting that we have of her.

“So anybody at all that may have seen Tia after that point on the Friday, we would ask them to contact us.

“And that may be in and around the school area or that may be further afield.”

Others came forward with information that Tia had planned on skipping school that day. She’s planned to meet someone. But despite their efforts, police really had no idea. A 12-year-old girl had vanished from her school, her body found six days later on a river bank, and nobody had any idea. Despite the cameras that pepper main roads, businesses and the dashboards of passing cars, Tia was nowhere.

Months went by without any major breakthroughs. But behind the scenes, the wheels were turning.

In late January, police approached the Crime and Corruption Commission and asked for help.

AT the end of a twisting corridor in the towering Fortitude Valley building that houses the CCC, is a small courtroom-like space that has hosted some of the state’s worst criminals. And in that space, some of the state’s worst crimes have been solved.

There are large glass windows with retractable blinds. A slightly elevated platform with a large desk and chair that looks like something a Magistrate would sit behind. In this room, often referred to as the “Star Chamber”, the chair is reserved for the Presiding Officer. They have a similar role to a Magistrate. They ensure the hearing is conducted fairly, that it is run in accordance with the law.

To the right is a place for the witness to sit. A carbon copy of a courtroom. There is a microphone, a computer screen.

And at the back, opposite the Presiding Officer’s bench, is a long table where the person asking the questions, the counsel assisting, stands. There is space for the witness’s legal representative, should they want one, and any investigating police who wish to sit in.

Other than a record keeper, there is nobody else. Private hearings are private.

Sometimes the witness is just that – a witness. Someone who might know something that could help solve a crime. Someone who perhaps is too frightened to tell police what they know. Or perhaps they did not want to give out information that could incriminate a family member.

They brought people in here when, four decades after Barbara McCulkin and her daughters disappeared, they thought there was an opportunity to compel long-closed mouths to open.

Witnesses who had been too terrified to speak out against someone long considered a hitman were told they must – or face prison for contempt.

Sometimes the person being questioned is already in prison. The CCC may be pursuing them for information on a co-accused, or an organised crime network. Outside the Star Chamber is a small cell where a person in custody can be held before being brought into the room.

Nearly 20 per cent of all coercive hearings now relate to murder investigations. Another 20 per cent involve drug trafficking.

But the CCC can’t bluster into any investigation. There are very strict rules relating to any involvement in a criminal matter. Forcing someone to answer questions, threatening them with jail if they won’t comply, is a massive breach of human rights – as well as basic fundamental legal rights. It is not done lightly.

But for those running the show, they see it as an invaluable tool. As powerful a tool as advancements in forensic science in some cases. They see coercive hearings as a way of heating up cases long gone cold.

Of the various categories that can invoke the power of the CCC, one is the “vulnerable victims” category. And that’s what Tiahleigh Palmer came under. As a child, she was considered a vulnerable victim. Often, child victims are attacked or killed in their home. Leaving family members the only witnesses.

And if those family members won’t co-operate with police, it can make things very difficult.

Approval for the CCC to come on board was given on February 3.

There were two suspects when investigators from the CCC met Queensland police.

One was an African man. Police had received information that Tia had planned to skip school on the day she was reported missing. They believed she’d planned to meet an African man.

“There is … some information there that would suggest that maybe she was thinking of wagging it that day so that would suggest she had a plan to meet somebody,” Det Hutchinson had told media in those first weeks.

The second suspect was a man whose mobile phone had “pinged” in the vicinity of the Pimpama River where Tia’s body was found. Police had received expert opinion on a particular geographic triangle where this mobile phone had connected with a tower.

With few leads and a positive sighting of Tia at the school that morning, these two men had been the focus of police investigations.

In addition to the sighting, police had also found Rick Thorburn’s blue Ford on CCTV. They’d found it in the vicinity of the school that morning. They’d not doubted his story.

The two suspects were – separately – brought into the Star Chamber. One of those men was grilled for two full days. The other for a single day. But it came to nothing.

In mid-February, police announced a $250,000 reward for information leading to an arrest.

Indemnity from prosecution – provided you weren’t the one to have carried out the schoolgirl’s murder – was up for grabs.

“We’re of the view there are people out there that have information about this homicide,” Det Hutchinson said. He was right – although, they were wrong about who they believed had that information.

A month later, Cindy Palmer, grieving, frustrated, nervous, fronted the media for the first time.

The press conference was held in Logan police station’s conference room – a large rectangular space with a u-shape arrangement of tables.

Journalists, photographers and camera crews crowded in.

She was brought in, flanked by detectives, to sit on a swivel chair.

“We’re appealing for anyone who knows what happened to Tiahleigh to come forward,” she said.

“Knowing this could happen to another family at any time while the person responsible is still out there … we definitely do need answers.”

A journalist asked Cindy to describe her daughter.

“It’s her birthday soon and she’s not even going to be able to be a teenager,” she said.

“Tiahleigh was a loveable girl, always loved mucking around. She loved dancing and couldn’t do cartwheels – but tried hard.”

She was clearly nervous. Her voice was flat, without emotion. She fidgeted and didn’t make eye contact. She wasn’t like other grieving parents at press conferences. There was no sobbing, no crying. No red eyes.

As the questions came to an end, as she got up to leave, a reporter shouted one final question.

Why, the journalist shouted, had Cindy’s daughter been taken away?

Police were furious. They had dragged Cindy in there because they hoped her appeal for information could help solve a murder. They viewed the question as insensitive and irrelevant. Cindy was quickly ushered from the room.

There was worse to come. Some television networks had broadcast the press conference via their Facebook pages. Within hours there were thousands of comments from people judging every aspect of Cindy’s behaviour.

She was attacked, savaged. She’d lost her daughter and fought for days to have Tiahleigh’s disappearance taken seriously, but to the thousands of keyboard warriors on the march, Cindy was as bad as the person police were looking for.

Why was Tiahleigh in foster care? It was too late for the mother to care about her now, people insisted.

In fact, Cindy would work as hard as police in her attempts to get justice for her daughter. She’d go to Tia’s school, hand out wristbands, speak to students.

All with a new baby, with other children to care for. Police were protective of Cindy. They were upset at the abuse.

“She’s turned her life around,” one detective said.

In late March, police spent four days conducting a thorough forensic examination of a house in Logan quite near Tia’s school. It was the former residence of a migrant family from central Africa.

Journalists who tracked the family down were met by denials that any of them had ever met the schoolgirl.

And so it went on. Nothing concrete.

Until two things happened. Two women, making separate approaches to police.

In late April, the mother of two of Julene’s home day care children was told a terrible story by one of her daughters. She reported Rick Thorburn to police. Suddenly, the concerned foster father, the man who carried the coffin of a little girl, was viewed in a whole new light.

Then, May 10. Another breakthrough. The phone call that cracked the case.

IT was a woman’s voice. They did not identify themselves. Police should be aware, the woman said, that a family meeting was held the night before Tiahleigh Palmer disappeared. One of the Thorburn boys had become sexually involved with their foster sister.

The CCC had already been in the process of eliminating the two suspects they’d brought in for coercive hearings. This would happen officially on June 10, when investigators officially ruled them out.

Now they had a new focus.

The hearings started on June 27. Rick, Julene, Joshua and Trent would all take their turn in the coercive hearings.

Anyone questioned in a coercive hearing is given a thorough briefing by the Presiding Officer. It is explained to them that they must answer questions. That they can have a lawyer present. That whatever answers they give cannot be used against them. But that investigators may use that information to conduct further inquiries.

Anyone refusing to answer questions could be jailed for contempt. Sentences in the first instance are generally around the six to nine months mark. It’s a terrifying prospect. Answer the questions or go directly to jail. But the CCC is not an outfit whose purpose is to punish. They are truth seekers. If you refuse to answer and go to prison, you can change your mind at any time. You can return to the Star Chamber, tell the truth, and they’ll send you home.

There is another important difference when it’s the CCC asking the questions. Police interviewing a suspect must take great care. They can’t cross examine. They can’t say “well, we know that’s not true”. Police interviews are filmed and used as evidence in court. They may be played to a jury. Calling a suspect a liar in a police interview could prejudice a jury. But a coercive hearing is not evidence to be used in a trial.

The Presiding Officer, or the counsel assisting can call someone a liar. They can say, “that’s ridiculous, nobody would believe that”. They can be forceful, demanding. They can tell the person they will go to jail if they don’t co-operate.

But when members of the Thorburn family attended hearings in the Fortitude Valley building, they used a different technique.

They wanted each person to put a version of events on the record. They had certain information and it was information the Thorburns didn’t realise the CCC had.

So the counsel assisting used a softer approach – he wanted to see whether Rick, Julene and the boys were planning to tell the truth.

What happened on the night before Tia disappeared? Was there anything of significance? Had there been any sort of family meeting? Had anyone in the house had any sexual contact with Tiahleigh during her time with the Thorburns?

They all lied. Their answers showed signs of collusion, of being rehearsed. In fact, it would emerge later that Rick had driven his boys to their separate hearings and told them to “stick to the line” when answering questions. He was a controlling, domineering man and he’d told everyone what to say.

Rick’s conduct in the hearing aroused massive suspicion. He came across as fake, his answers concocted. He recited his answers calmly, matter-of-fact. But in the breaks he cried fake, almost comical, tears.

Tia, he said, had been welcomed into their home. She’d been cared for. During a trial weekend, to see if she would fit into their household, he’d been very impressed.

“That’s the kid for us,” he’d told Julene.

But they had discovered one very important fact since that Crime Stoppers call was made. For the first time, they were aware that Rick had been alone with Tiahleigh the night before she was reported missing.

‘You’ve lost two licences, and you’re only a learner’

A learner driver copped an earful from an Ipswich magistrate over his astonishing accumulation of demerit points.

‘Night beautiful’: Mum accused of attempted murder

A mum accused of trying to murder her four-year-old daughter - by 'gassing' her in a car - has been sentenced for breaching her bail conditions by spending time with the girl.