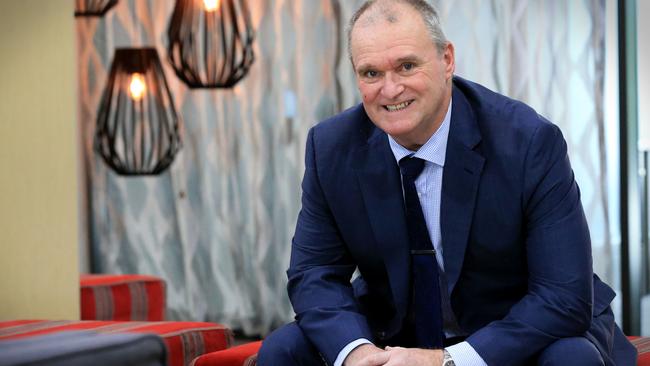

Former Rebels bikie and Army major Steve McCrohon to become lawyer

He’s a former Army major-turned Rebels bikie who will soon be defending accused crooks after leaving the outlaw gang to study law. But he’s defended the Rebels saying it is ‘just like a footy club’.

Crime & Justice

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime & Justice. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A FORMER Army major who joined the Rebels will soon be defending accused crooks after leaving the bikie club to study law.

Steve McCrohon, 59, who led Australian forces in Rwanda during the 1995 Kibeho massacre in which 4000 locals were killed, will sit his final exam next week and plans to begin practising law this year.

The 26-year Army veteran, who also served in East Timor, was for a decade a patched member of the Albion chapter of the Rebels Motorcycle Club.

But he said he was not a bikie or a thug, and his criminal record was squeaky clean.

He even credits the club for supporting him after being diagnosed with PTSD.

FAKE PRINCE’S SECRET JAILHOUSE LETTERS REVEALED

“After I left the Army I went into a social activity that’s fairly well frowned upon these days, but it was those guys that really helped me,” Mr McCrohon said.

“You hear a lot of ghost stories. People say you’ve got to commit a crime to be in the club. No way in the world.”

MOMENT COPS UNCOVER 1KG OF METH AT ROADSIDE STOP

Mr McCrohon said truck drivers, business owners and tattoo artists were Rebels and the club didn’t carry the same “stigma” as it did in the early 2000s.

“I don’t want to sound naive, but it’s like being in a football club. There are a lot of people involved but you might mix with half a dozen of them. You know others, but you don’t all mix, and sometimes you don’t want to mix,” he said.

“One of the first comments said to me by a fairly well-known figure was, ‘if anyone says you’ve gotta do something illegal, you don’t’.

“I am not going to sit here and be naive enough to say there weren’t some bad buggers in bike clubs, but the bottom line is I never saw it and I never mixed with it.”

The father-of two said he left the club because he wanted to study.

He said VLAD laws had also made it harder to spend time with mates in the club.

“I put my hand up to leave because the lads knew I was going to study … I got handshakes all-round and they said, ‘thanks for everything, you’re always welcome’. They didn’t take my house or my bike or any of that,” he said.

Mr McCrohon grew up in Rockhampton and was young when his father died after being spear-tackled in a football game.

At 17, Mr McCrohon left home and joined the Army.

“I just fell in love with the camaraderie and the mateship,” he said.

“It was an adrenaline rush. When on operations and you’ve got your flak jacket on and your weapon on … you’d just feel the rush. It was like a natural drug.”

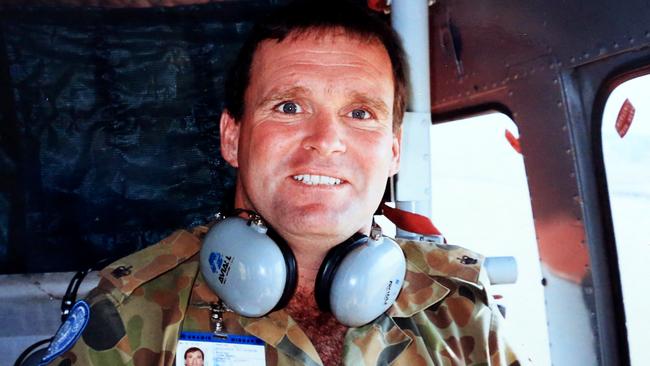

In 1995, Mr McCrohon led 108 troops to the African nation of Rwanda to provide security for medics sent to the country by the United Nations.

Much of their work was at Kibeho refugee camp, where more than 100,000 displaced people were living.

About three months into the deployment, Mr McCrohon got wind the military wing of the Rwandan Patriotic Front was trying to close the camp. On April 22, 1995, he said, “s--t hit the fan”.

The massacre started with a warning – three bodies dumped – and soon, Mr McCrohon was threatened with a gun to his head.

“You see the worst things in society, what people can do to each other,” he said.

Two days later, he went to the Australian Army base in Kigali to organise a potential exit route.

“My troops counted 4000 dead,” he said. “There were six-month-old kids killed. There were 80-year-old men and women killed.”

But under their rules of engagement, the Australian Army couldn’t return fire.

“Every day I have carried the burden of putting those lads there. I was about age 35 but a lot of these young men were 19 years old. They saw more killings and deaths than many other soldiers had seen previously in other conflicts.”

It was getting his mental health back on track after leaving the ADF that drove Mr McCrohon to study. He said it took many years to accept he suffered from PTSD.

“In hindsight, that was the cause of my marriage breakdown. My wife up and left and she said to me: ‘You came back from Rwanda a different man’. I think I did.”

A chance encounter with a former soldier and veteran, Dave Garratt, now a partner at Brisbane law firm Howden Saggers Lawyers, sent Mr McCrohon to law school.

“I’ve had to keep reminding myself as I go, and when the workload seems tough, that I’m doing this as a mental health project. I just hope I can give something back.”