Fitzgerald Inquiry: The media lawyer reveals the lies and threats in the battle for a harsh truth

“IT HAS been said, and not entirely in jest, that Sydney is the most corrupt city in the western world, except of course for Newark, New Jersey and Brisbane, Queensland.”

Crime Reads

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime Reads. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Ex-premier: More dark secrets to be revealed

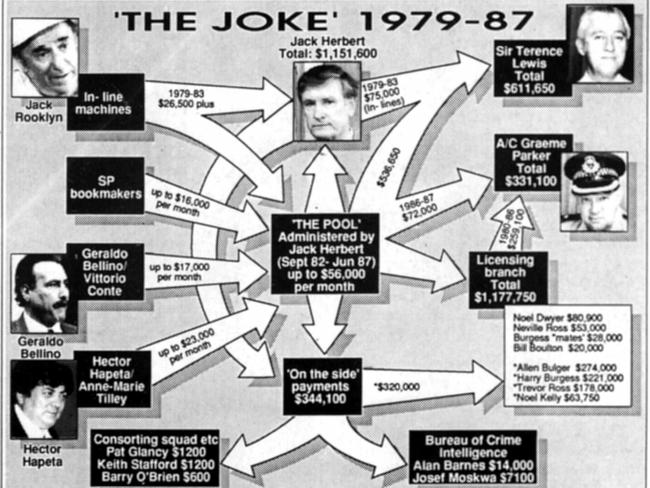

- How crooked cops ran The Joke

- Fitzgerald Inquiry: Where it all began

“IT HAS been said, and not entirely in jest, that Sydney is the most corrupt city in the western world, except of course for Newark, New Jersey and Brisbane, Queensland.”

Evan Whitton, multiple Walkley Award winner, editor and crime author commenced Can of Worms, in 1986, with that quote. The expose of corruption in NSW was published the year before Fitzgerald QC commenced work.

After covering the Fitzgerald Inquiry, Whitton later wrote, “it was the biggest and most important story I ever worked on. The experience of a career”. As a media lawyer I felt the same.

In January 1987, I had been advising The Sunday Mail and The Courier Mail for over 15 years. The work involved legalling stories daily.

I had seen little of the work of a young journalist Phil Dickie who came to my office, bearing a referral from the Courier’s Deputy Editor, Greg Chamberlin, and the Chief of Staff, Bob Gordon. He told me he had been assigned to uncover the ownership of Sin Triangle at the top of Fortitude Valley. Gordon had moved up from Canberra and was intrigued by an apparent brothel operating in clear view of passers by, as he came to work at Bowen Hills. All Hallows’ schoolgirls walking or on buses travelling to school passed the premises daily.

Dickie produced a draft story, a copy of the year old Sturgess Report into illegal brothels, a series of Titles Office, BCC and VG Department searches plus a list of massage parlours. With help from a number of undisclosed informants, he had correctly identified criminals and businessmen given numbers in the Sturgess Report. He had painstakingly cycled to and trudged around parlours throughout the city.

After minor changes to Dickie’s story, I phoned the Deputy Editor to discuss the ramifications of publishing a who’s who of organised vice in Brisbane apparently unchallenged by police. I outlined steps needed to sustain defences of truth or qualified protection. On some of the material it would be necessary to establish that the matter was published without malice and in good faith on a matter of public interest.

In July and August 1971, three detectives from Commissioner Ray Whitrod’s CIU had interviewed prostitute Shirley Brifman at the chambers of Colin Bennett, barrister and Labor MLA for South Brisbane. Brifman was a confidant and informant for Tony Murphy, a member of the “Rat Pack”(comprising Terry Lewis, Murphy and Glen Hallaghan) within the police force.

She had been crucial in defeating a serious threat to corrupt Queensland police at the 1964 Royal Commission into the National Hotel. One of the staff at the National had told Bennett that the Hotel had provided alcohol and meals to Commissioner Bischof, Murphy and others while prostitutes operated openly from the rooms and lounges.

Bennett in parliament in 1963 complained of police touring the state and soliciting votes for the Nicklin Country (National) Party government. In a throwaway line at the conclusion of his speech, he accused the government and police of complicity in covering up the hotel’s activities.

Despite direct evidence from two staff members, Brifman, policeman Jack Herbert, Murphy and others gave false evidence discrediting the claimants. The Inquiry did not find proof of any wrong-doing. The platform was laid for several decades of institutionalised police and government corruption.

I did not obtain a copy of the Brifman interviews either in Brisbane or at Sydney (by honest NSW police), until years later but many of the allegations were known by Brisbane journalists and lawyers.

In 1971 Brifman confessed her actions on national TV and accused Murphy of perjury. She identified the Rat Pack members as “Bischoff’s collect boys”. A perjury charge was laid in 1972 but Brifman died, probably by suicide, before the court hearing and Murphy was discharged.

At a public address in 1988 Ian Callinan QC said that both he and Fitzgerald QC were aware that the police were not “clean” as the 1964 inquiry had claimed, and considered the reasons for its failure.

Col Bennett was embittered by the National Hotel outcome and repeatedly attacked the Rat Pack in and out of parliament.

Several successful defamation actions by Murphy against Queensland Newspapers and Channel 7 in the early 70s gave him significant payouts in settlements. Lewis and Murphy also harassed (with court action) two honest police officers who made Rat Pack allegations on TV.

I was naturally cautious of stories containing allegations of corruption against senior police, directly or by implication.

The first Dickie article: “A year after Sturgess, sex-for-sale businesses thrive unchallenged” appeared on the front page of the Courier on 12 January 1987. It caused a storm in public and government circles.

Dickie had contacted Des Sturgess to verify the names of criminals Hector Hall (Hapeta), Anne-Marie Tilley, and the ‘Syndicate’ of Geraldo Bellino, Vic Conte, Geoff Crocker and others against numbers listed in the Report. This Sturgess did, but on our side there was considerable unease that a wrong name would lead to a substantial defamation payout.

Official reaction to the first and later stories was predictable. The newspaper was accused of dragging up old discredited allegations. Stopper writs arrived from owners of some of the 26 identified brothels. The Police Minister Bill Gunn claimed there were only 14 massage parlours in Queensland and no prostitutes working in them.

Several years earlier Minister Russell Hinze claimed that illegal casinos in Brisbane were “non-existent”, a cause of merriment to journalists who had been there.

The stories by Dickie continued. The themes were inaction by police on Vice, Drugs and Gambling. On 13 April, “ Brisbane’s casinos flourish despite Gunn’s vow to close them”. On 18 April, “ Organised crime group revolutionises the sex-for-sale industry.”

Our side’s confidence was growing along with the defamation writs in my filing cabinet. At the end there were some 17 in all, but none proceeded to any degree past the writ stage.

Our confidence was boosted by the ridiculous responses from the Police Media representative to questions which Dickie and I had agreed.

Had the Licensing Branch taken action against any of the named criminals in the previous twelve months? What explanation did the police have for inaction against Hapeta and others? These elicited answers after prolonged delay of “No” and “No Comment”. On querying Hapeta’s activities, we were told he was a resident of Sydney with no connection to Queensland prostitution.

There has been much speculation as to whether the stories alone would have led to a Royal Commission, without the ABC Four Corners program, The Moonlight State. Police and government may have ridden out the storm as they had before. At the finish, Dickie and young police informant Nigel Powell were collaborating closely with the ABC’s Chris Masters and touring the unsavoury areas of Brisbane.

The visual impact of the ABC production showing the Queensland premier singing in church interspersed with grainy shots of seedy ‘red light’ parlours probably turned the tide.

The Fitzgerald inquiry became a template for similar actions in other states and showed how entrenched corruption can subvert democracy and the rule of law.

The recent jailing of one of the last of that generation of notorious Sydney cops, Roger Rogerson, hopefully brought to an end the activities of police killers and standover men identified by Brifman in Sydney.

There is also a vital current debate on the role of ICAC in NSW and whether it should be extended to the federal sphere.

For my part, I must acknowledge the extraordinary efforts of Peter Applegarth and Russell Hanson QC throughout the long inquiry. The ABC similarly benefited from Robert Mulholland QC.

Lastly, I had for many years a second hand book by a Brisbane author, best left anonymous, entitled In Place of Justice: an analysis of a Royal Commission, 1963-1964. It has passed out of my possession. This publicly spirited man had personally financed the book by a small publisher outside Brisbane. It was a detailed account of the injustice perpetrated on David Young and Geza Komlosy, the two National Hotel staffers in 1964 and a virulent attack on police “assisting” the Commissioner.

It languished for years largely unread. It was published without fear of repercussions. It gave me some insight into police activities. If the author is still alive, thanks.