Bid to find location of Jessica Gaudie’s remains

DEREK Sam won’t reveal where he hid teenager Jessica Gaudie’s body but police believe when they find her, they may uncover two other women who crossed paths with the convicted murderer.

Crime & Justice

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime & Justice. Followed categories will be added to My News.

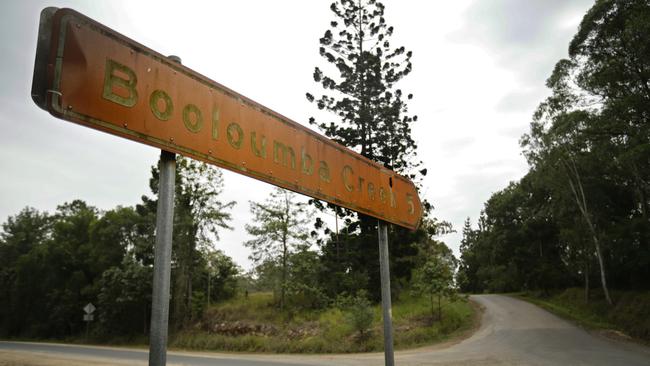

SECRECY was paramount. Had the media got wind of the visit, the area would have been swarming with news crews, but the police car went unnoticed as it turned into Booloumba Creek Rd last October.

The thin gravel strip, about 12km south of Kenilworth in the Sunshine Coast hinterland, winds through a patchwork of farms before hitting an area accessible only by four-wheel-drive, beyond which lies lush rainforest and pristine mountain streams in the vast Conondale National Park and adjoining state forests.

Derek Sam, sitting in the back of the police car, was no stranger to the serene pocket of countryside — once he’d known every curve of the road, but it had been years since he’d been there.

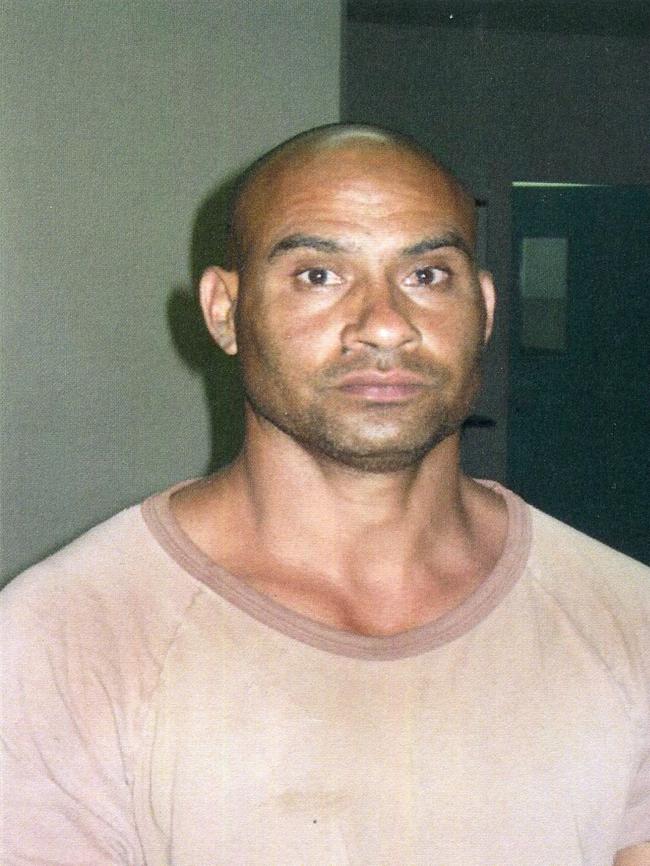

Sam is a convicted killer serving a life sentence for the 1999 murder of Nambour schoolgirl Jessica Gaudie. Detectives had plucked him from his cell at Lotus Glen Correctional Centre, near Mareeba in far north Queensland, and brought him 1600km south to his old stomping ground because they suspected Sam was the rarest and most dangerous breed of criminal: a serial killer.

Somewhere nearby, police believe, Sam may have hidden the bodies of three people: Gaudie, whose remains have never been found; British backpacker Celena Bridge, who was last seen on Booloumba Creek Rd in July 1998; and Kenilworth teacher’s aide and mother-of-two Sabrina Ann Glassop (commonly known as Ann), who vanished from the same road in May 1999.

Detectives accompanying Sam were looking for any crack in his facade, and for a brief period he became unsettled, even teary. Then the mental wall went up again and Sam shut down.

There have been many attempts to crack Sam over the years. All have been to no avail, but police may now have the best chance of solving the mystery.

Derek Sam was in a rage. A blind, clenched-fist, red-mist kind of rage. His former de facto, Mia Summers, was cosying up to a man right in front of him at a birthday party at a house in Bonney St, Nambour. Beautiful Mia, then 25, was finally free of Sam and daring to flaunt it, or that’s how Sam saw it.

It was the early hours of August 29, 1999. John Howard was prime minister and Bill Clinton the US president. Y2K computer bug fears gripped the world as the year 2000 loomed and the Sydney Olympic Games were more than a year away. Eight bodies had that year been discovered in barrels in a disused bank vault at Snowtown, 140km north of Adelaide, and two teenagers had gunned down teachers and students at Columbine High School, in the US state of Colorado. On the radio, grunge rockers Pearl Jam had been top of the Australian singles charts for four weeks with a cover of a 1964 song, Last Kiss. “Oh, where oh where can my baby be? / The Lord took her away from me”, went the opening lyric. By the end of that night, someone else’s baby would be taken from them.

Sam had never seen Mia with another man. They had been together since they were 14-year-old schoolkids in Bamaga, about 40km south of the northern tip of Cape York. Sam had been raised in a church-going Bamaga family and Mia’s family moved to the Cape for her father’s work. She was slightly built with fair skin and red hair. They had three kids and had moved around the state together, regularly breaking up but always reuniting. This time was different, and the more Sam drank, the more it became a problem that Mia was there with someone else.

Some people have issues with alcohol, but Sam had serious issues. Whenever he got on the booze, things tended to go horribly wrong.

The party was for one of Sam’s workmates and Sam was behaving so erratically that some of the guests — knowing him as generally quiet and reserved — thought he must have been stoned on marijuana.

He punched Mia’s new love interest, then stumbled out to his 4WD, a brown 14-year-old Toyota LandCruiser. Someone tried to grab his keys but Sam, 25, was fit and wiry and it was like trying to stop a freight train.

He slammed the door of the 4WD and roared down the street, narrowly missing another car and a reveller before hitting the kerb on the wrong side of the road. One of the doors flew open from the impact, then the tail-lights disappeared from view. A “Bad Boy”sticker was on the back of the 4WD.

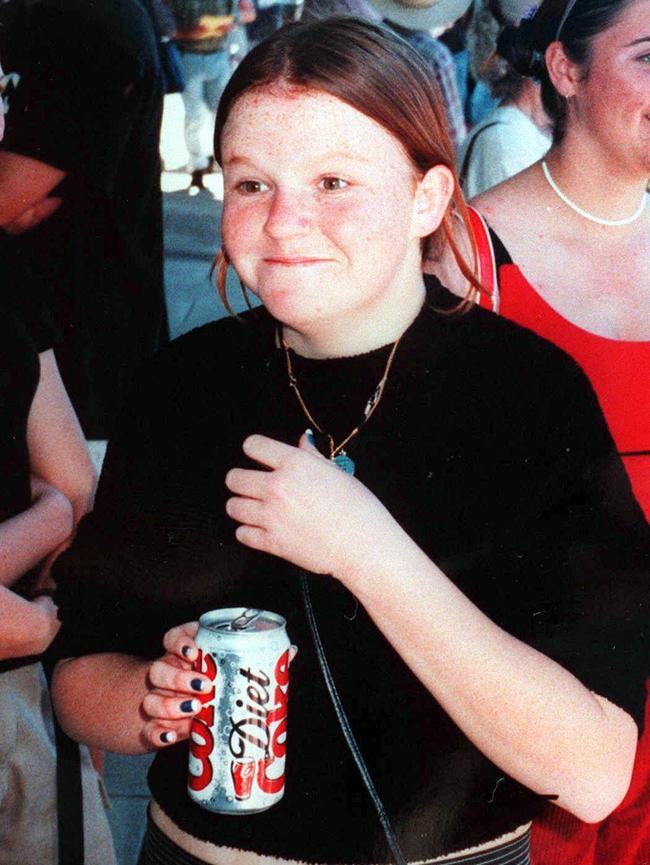

About 2km away, at Mia’s Ridgewood St home, 16-year-old Jessica Gaudie was babysitting Sam and Mia’s children, who were six, three and one. Sam was living elsewhere in Nambour.

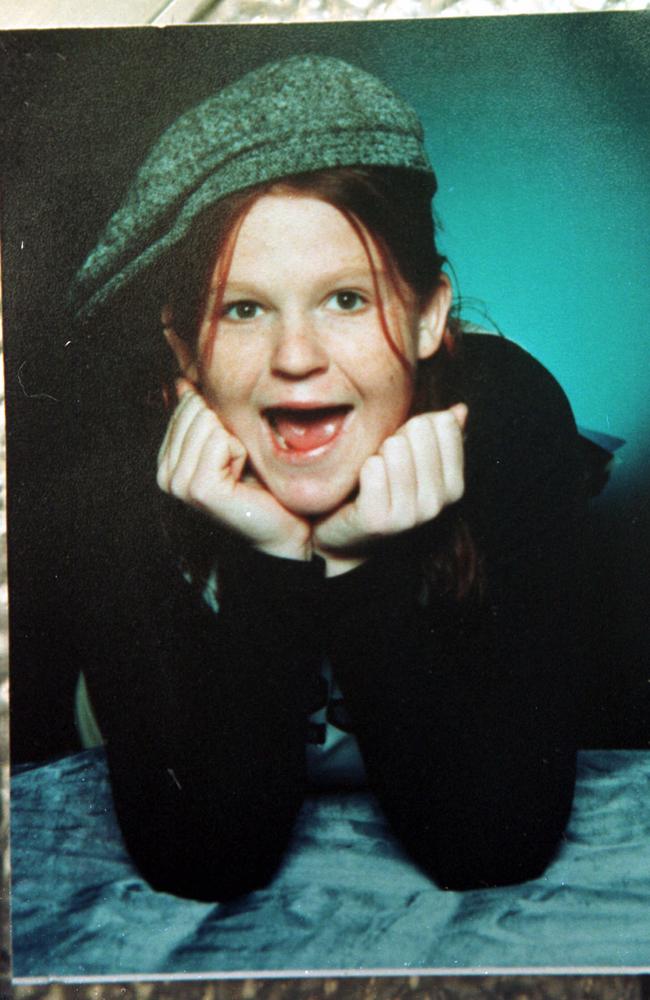

Freckly, red-haired Jess was in Year 10 at Burnside State High and lived around the corner from Mia. After Mia had gone to the party the kids had played games inside while “Big Jess”, as they affectionately called Gaudie, watched television, before they’d all gone to bed.

About 2am the eldest of the three children, Nakita, woke and peered out her window to see her father getting out of his 4WD.

There was a knock on the rear laundry door and Gaudie, wearing a loose red jumper and silk boxer shorts, got up from a mattress on the floor of Nakita’s room to see what he wanted. There was a muffled conversation and then Sam’s vehicle drove off.

“And Jessica didn’t come back in my room,” Nakita would say later. “I kept on waiting for Jessica to come back and she didn’t.”

Gaudie was meant to be home early in the morning to go to a triple christening for a niece and two nephews.

When she didn’t arrive, her older married sister Kelly Dodd, who lived nearby and was 26 at the time, walked to Mia’s place.

“Jess wasn’t there,” Dodd recalls. “At that point I began to panic because her shoes were still there, her bag was there, the money she got for babysitting was still on the bench. All her belongings were still there, but she wasn’t. So then I ran home and I rang the police straightaway. It was not her to do that.”

Mia had gone straight to bed after the party and hadn’t realised Gaudie was missing until Dodd turned up. But thanks to Nakita’s chance sighting of her father through her bedroom window, police instantly had a suspect.

Two detective senior constables from the Sunshine Coast, Mark Wright and Peter Brewer, interviewed Sam at Nambour CIB later that night. Sam told the officers he’d known Jessica for about six months; she used to go around to Mia’s a fair bit and he would offer her lifts home from school.

Sam admitted going to Mia’s house early that morning and taking Gaudie for a drive, but he claimed he dropped her off near the party so Mia would be forced to go home to be with the kids. Gaudie didn’t turn up at the party.

After the interview, Wright and Brewer drove Sam back to his home and asked for the clothes he was wearing. He pulled a shirt out of the dryer; it was still damp from being washed.

For police, there was a dawning realisation that Gaudie’s disappearance could be part of an even bigger and more sinister set of events. Sam worked as a supervisor at Piabun Farm, where young Aboriginal offenders could stay instead of going to youth detention.

The property was on Booloumba Creek Rd, where in the previous 13 months two women had vanished without a trace.

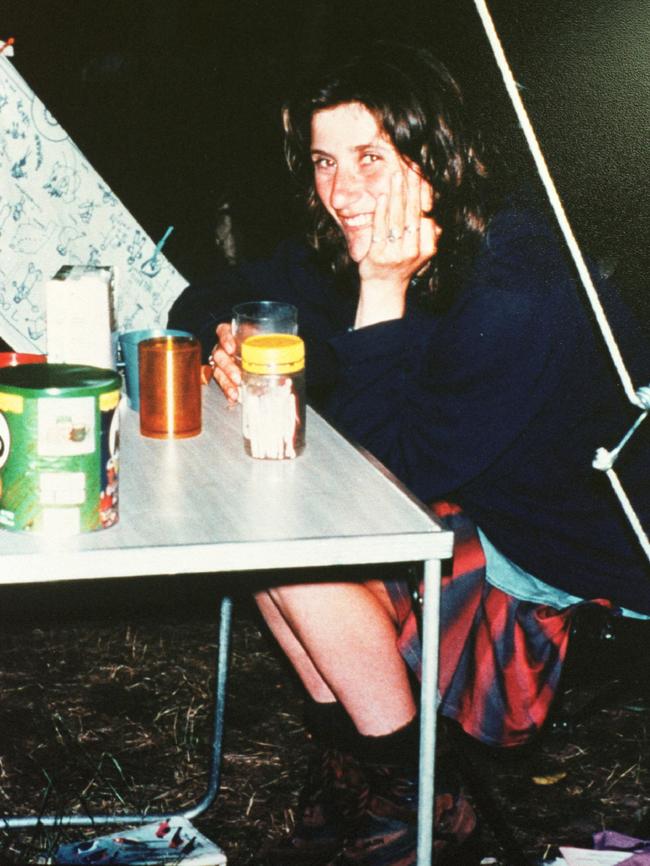

She was walking alone with a heavy backpack crammed with camping gear, a 28-year-old tourist who was more than 16,000km away from her home town of Carlisle in northwest England. Celena Bridge had an environmental science degree and a thirst for adventure. She was in Australia for three months to study bird life and ecosystems.

On July 16, 1998, after spending a couple of nights at Conondale’s Crystal Waters permaculture village, she had made her way to Booloumba Creek Rd, about 30km away, to meet up with a birdwatching group at a camp ground.

Police would later describe her as “165cm tall, of slim build, tanned complexion, with brown hair and green eyes”, but photos show her with fair skin and her hair with a red tinge.

A woman who lived on the road saw her passing by and they had a chat at the gate. The resident was worried about Bridge being there on her own and told her so; the area looked tranquil but it was isolated.

Bridge assured the woman she was OK and walked on. She stopped again down the road, this time outside Piabun Farm, where she asked a supervisor, Geoff Turner, for directions. The camp ground was 1.5km away and she kept walking.

According to police, a witness says Sam drove out of Piabun Farm soon after and turned right, heading towards Bridge. She was never seen again. It was almost a month before the alarm was raised, when Bridge failed to meet her boyfriend, Jonathan Webb, as arranged at Brisbane International Airport when he arrived from the UK in early August 1998. Webb contacted police, who initially suspected a hiking accident.

Bridge’s parents, Lionel and Beth Bridge, flew to Australia from England to search for her. They returned home without their beloved daughter. “We think the most likely thing that has happened is that she’s had an accident,” Lionel Bridge told media. “But there is always the possibility in the back of our minds that something else has happened. We have no hope — it’s a terrible thing to say but we’ve got to be realistic.”

Like everyone else from the area, Sabrina Glassop would almost certainly have been worried sick about the missing backpacker. Little did Glassop know that she would soon go missing too.

Glassop, 46, lived on the corner of Booloumba Creek Rd and the Maleny-Kenilworth Rd. She had separated from her husband, forestry worker Eric Glassop, but they remained friends and had dinner at her home the night before she disappeared. Eric, who lived nearby, left about 8.30pm, saying he’d be back the next morning with newspapers and fresh bread for breakfast.

About 6am the next day, May 29, 1999, Glassop’s parents, Joan and John Worsley, who lived in a caravan on the same property, heard her red Suzuki speed off towards Kenilworth. Unusually, the gate to the property was left wide open, suggesting Glassop was in a rush.

Her car was found about 500m away at the Little Yabba Creek rest stop on Maleny-Kenilworth Rd, where she was known to walk her poodle, Poppy.

Unlike the delayed reaction to Bridge’s disappearance, there was an immediate and large-scale search for Glassop. The result, however, was the same.

Glassop could not be found, and nor could her dog.

The two women, though almost 20 years apart in age, shared a physical resemblance; photos show Glassop with a fair complexion and red hair. Three months after Glassop’s disappearance, Gaudie went missing.

Piabun Farm had started with the best of intentions. The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody of 1987 to 1991 had led to a push to break the cycle of recidivism of Aboriginal youth.

As a result, the Piabun Aboriginal Corporation secured funding to set up an “outdoor rehabilitation and diversion centre” and bought a 58ha rural property on Booloumba Creek Rd in September 1994 for $400,000.

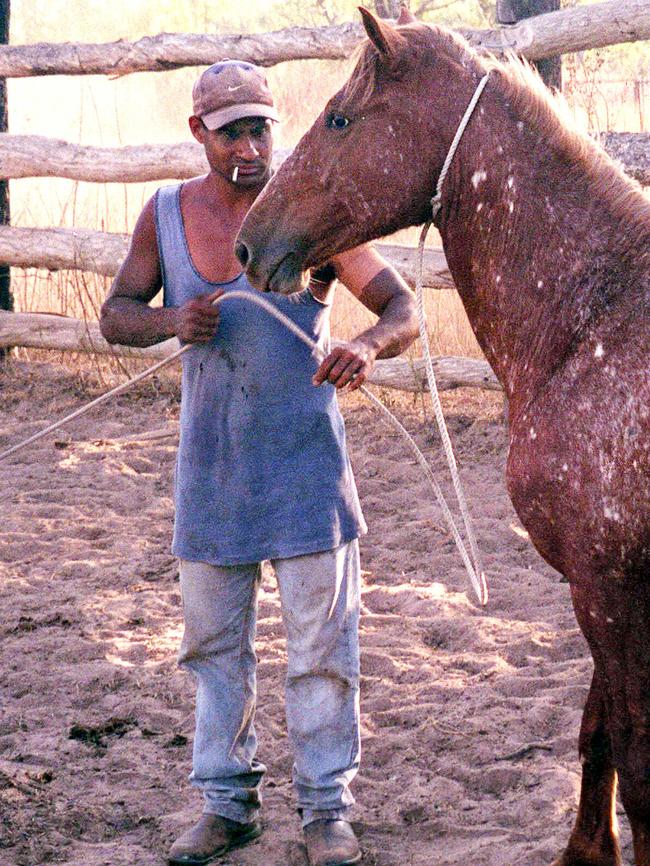

Within weeks, boys were arriving from youth detention centres to stay in dormitory accommodation at the farm. The idea was for the boys to be taught traditional laws and practical farming skills such as horse-breaking and riding. It was run by Mark Johnson, a cowboy hat-wearing horseman with a bushy moustache, who hired Sam as an assistant.

Years earlier, Sam had run into trouble as a 13-year-old and had been sent to Petford Training Farm, a diversionary camp for indigenous youths that had been running near Atherton since the 1970s.

Petford manager Geoff Guest would recall Sam as having done well at the farm as a teenager, showing he had a “natural ability with horses”. But after he went home he found himself in trouble again.

“He got back into the drink and the dope and got into trouble with the police,” Guest said in 2009.

“Derek was sent back here after he was arrested walking down the middle of the street with a gun or a knife, I can’t remember which exactly. He was 17 then.”

Sam put his troubles behind him again at Petford and was hired to work as a horse trainer there. Then in September 1997 he was poached to work at Piabun. Guest had concerns.

“I was really worried when he left because he had no support and he started drinking and smoking dope again,” Guest said.

“Derek was not the sort of bloke who should drink. He had alcoholic tendencies. When he got on the drink and the dope, Derek became a different person.

“It was well-known Derek got aggressive when he was drinking and had a history of misbehaving under the influence. He would black out and not remember anything he’d done … When he was under the influence, Derek was capable of anything.”

Typically, five or six juveniles at a time would stay at Piabun. They’d feed horses from 6am, then do farm work including fencing and slashing, horse work and riding. Sam would also take paying international guests on 40km horse rides to Kenilworth and through the surrounding forests.

There were countless roads and tracks to explore and Sam got to know them well; some areas were treacherous, with abandoned mine shafts all over the place.

Things were soon going off the rails at Piabun, which has since ceased operating. The Queensland Government — concerned about financial management and accountability — slashed funding.

Claims would later emerge that boys had been harshly treated and forced to fight each other. Tragedy struck when a teenage boy, Howard “Harry” Cobbo, committed suicide in a tractor shed, and claims arose that he had been bullied and assaulted.

Ken Schroder, who still owns a property on Booloumba Creek Rd, had a run-in with Piabun’s manager Johnson for running cattle on his land without permission. A fire later broke out on Schroder’s property and he suspected someone from Piabun might have lit the blaze deliberately, but he didn’t make a complaint to police.

Meanwhile, Piabun’s youths were escaping and trekking to Kenilworth, where they were suspected of being involved in petty crimes like breaking into cars.

“It was a very tense, frightening atmosphere at that time,” says Schroder.

Schroder’s ex-wife was the resident who talked to Bridge the day she was last seen alive.

“It was very unusual to see backpackers, let alone single women backpackers, just walking along the road by themselves,” Schroder says. “You’d see people on horses, but not just people tramping along the road.”

On the day Gaudie vanished, police seized Sam’s 4WD and found it had been thoroughly cleaned. Police officer Mark Wright, who interviewed Sam that day and became one of the main investigators on Gaudie’s case, is now a sergeant based in Coolum.

He recalls the 4WD “lit up like a Christmas tree” when sprayed with Luminol, a substance which reacts to blood and other substances including cleaning agents.

The only confirmed blood was found in the boot, in two small stains, but Sam claimed injured wildlife had been in the 4WD and forensic tests were inconclusive.

Sam had filled the 4WD with fuel the day before and, based on the fuel levels, detectives found he could not account for between 75km and 150km of travel.

Sam claimed he drove to Coolum the morning after the party and sat on the beach.

Wright asked him, “What, all day?” and Sam replied, “Yeah”.

Police thought he’d gone to dispose of the body. “That puts him able to get out to the bush where he knows the area at Booloumba Creek and back,” says Wright.

A strand of hair was recovered from the jeans Sam was wearing on the night, but it did not yield any DNA.

Wright and his detective colleague Brewer travelled to Bamaga to follow up on the stories Mia had told them.

The relationship had been marked by violence when they lived there; when Sam had been drinking he’d throw her around and pull her hair and push his clenched fist into her jaw.

Sometimes he’d bite her. He had a rifle and would put the barrel in his mouth and threaten to pull the trigger until she talked him out of it. After one fight, Sam had walked into the bedroom and fired the gun into the floor, just a foot from where Mia was lying.

Police came and took the gun at the time.

“We saw the damage to the concrete floor,” Wright confirms.

After another argument Mia had gone to a church, only to have Sam ride inside the building on a horse, like some crazed cowboy, to demand she leave with him.

Things were at their worst when he was drunk, and in Bamaga this was often.

He’d drink until there was nothing left to drink, bingeing all day and all night, then demand sex. He became moody, aggressive and violent when he didn’t get his way, then when he sobered up he’d say he couldn’t remember.

The couple moved from Bamaga to Cairns and Sam agreed to stop drinking, but his abstinence didn’t last.

After the birth of their first child, Nakita, they had an argument and Sam grabbed his daughter and a knife and threatened Mia.

It was the final straw; Mia called police, took out a restraining order and left Sam. But within months they were back together. It was on-again and off-again for years.

They ended up living together at Piabun Farm as “house parents” for the boys sent there. July 1998 — when Bridge went missing — appears to be one of the “off again” times in the relationship. Mia told police she had moved to Cairns at the time, while Sam had stayed on at Piabun.

They got back together in September 1998 and eventually moved into the house at Ridgewood St, Nambour. Mia told police they broke up for the final time in May 1999 — the same month Glassop went missing.

Because of the kids, Mia would let Sam visit for Sunday night dinners and to watch videos. They’d agreed they would just be friends, but Sam wanted more. After watching a State of Origin football match one night, he’d kept telling Mia she was beautiful, but when she flatly refused his demands for sex, he called her a slut and a bitch and said he wouldn’t pay maintenance.

About seven weeks before Gaudie went missing, Sam lost it badly, accusing Mia of sleeping around. She’d told him it was none of his business and he’d leapt over and grabbed her around the throat with one hand as she sat in a lounge chair.

With her life in his hands, he squeezed; then he calmed down and let go.

Piabun’s manager, Johnson, was initially hostile towards police but then provided a detailed 18-page statement that was damning for Sam. Johnson told detectives he went on at least two drives with Sam to go back over the events of the night Gaudie disappeared.

According to Johnson, Sam appeared confused and seemed to have trouble remembering what happened, saying he thought Gaudie might have had a head injury.

Detectives arrested Sam on September 28, 1999, and charged him with Gaudie’s murder. At his trial in the Supreme Court in Brisbane in 2001, prosecutor Brendan Campbell said the only rational explanation for the disappearance of a “happy and normal” teenager was that Sam murdered her.

The jury, after deliberating for 12 hours, agreed and convicted Sam of murder.

Wright and Brewer went and confronted Sam in prison after his appeal failed.

“He got brought up (from his cell) and they didn’t tell him it was us. When he got there, he went off. He was sick of us,” Wright says.

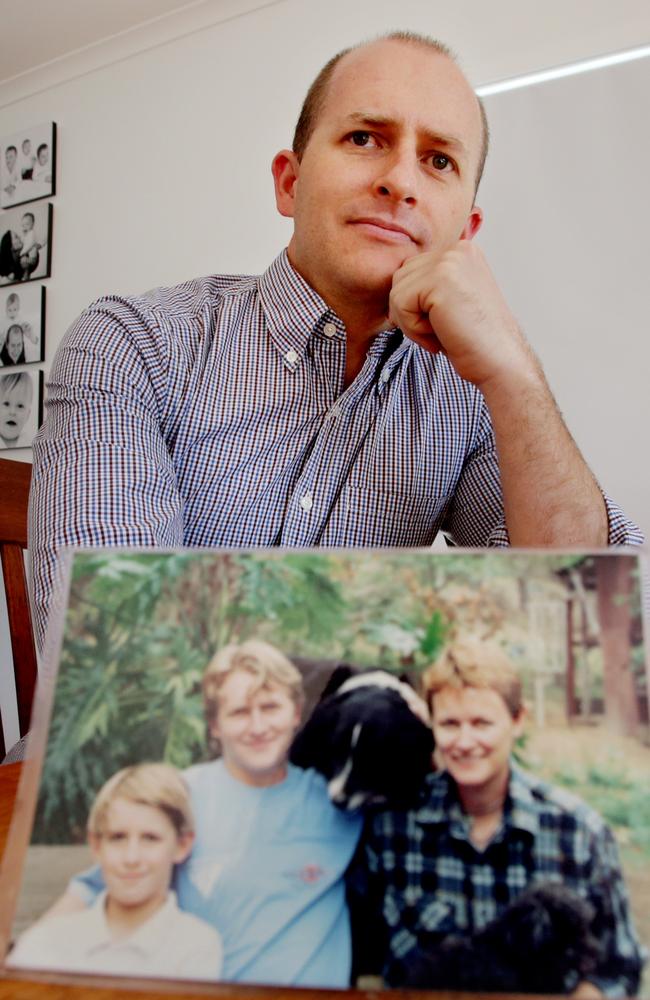

The detectives changed tack and asked Gaudie’s sister, Kelly Dodd, now 44 and living on the Sunshine Coast, for help. Dodd agreed to confront Sam in prison. Wright and Brewer drove Dodd to prison and escorted her inside, but then she was on her own. She had a plan for what she was going to say, but it was all forgotten when she came face-to-face with Sam.

“I was crying. I got him upset at one stage. The whole time I was in there I was asking where Jess (was),” Dodd says.

“He just denied it the whole time — just kept saying, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I didn’t do it’. We spoke for about 45 minutes and I got nothing from him.

“There could be a number of reasons why he doesn’t admit to it. Maybe Celena (Bridge) and Ann Glassop are at the same location Jess is at. He might have just talked himself into it that he is innocent. I don’t know.”

Dodd reveals that since the initial prison visit, she has tried to see Sam on two more occasions. Once, she drove to Maryborough, 250km north of Brisbane, where Sam was then jailed, but he wouldn’t meet her. It’s a mark of both her courage, and his lack of it.

“He won’t agree to it. He won’t see me,” she says.

Wright recalls of Dodd’s prison visit: “It was pretty nerve-wracking for her. It’s pretty daunting, especially if you’ve not been to (prison) before. And then to confront the person who has been found guilty of murdering your sister. It was pretty brave of her. But they were desperate enough to try anything. From memory she thought at one stage he was going to roll, going to tell her, but then he just backed away, like he always does.

He’s cold and calculating. To give the bodies up, that would bring shame to his family. But it also exposes him for what he is.

“The problem we’ve got is I believe the three ladies’ bodies are together or in similar circumstances or nearby to each other. If we find one, we’ll find all three.”

No one has ever been charged over the disappearances of Bridge and Glassop and Sam has denied any involvement.

An inquest was held at Maroochydore Coroner’s Court in 2002. Sam’s workmates told the inquest they saw Bridge on Booloumba Creek Rd; but Sam, according to media reports, said he could not tell if the person he saw was a man or a woman. One witness said that while watching a television report about Bridge’s disappearance, Sam said he’d seen the backpacker at a camp ground.

Another witness, Piabun worker John Poole, said that only weeks before Glassop went missing, Sam boasted he “had a date with a schoolteacher”. His date was “a lovely lady … with a beautiful body”. The inference was that he was talking about Glassop, a teacher’s aide.

“She’d be a good f---,” Sam is alleged to have said.

While horseriding near Little Yabba Creek after Glassop went missing, Sam is said to have opened up some more to Poole.

“They won’t find her down there,” Sam said, according to Poole. When Poole asked why not, Sam laughed and said: “I’m a blackfella and a black tracker.”

Sam had previously helped Glassop with her horses; he’d once taken her shetland pony to a school fete. And the night before Glassop went missing, he’d been drinking at a party and could not account for his movements.

When called to give evidence at the inquest, Sam insisted: “It wasn’t me”. He’d been convicted of Gaudie’s murder “but I didn’t kill her”. Coroner Paul Johnstone found Bridge and Glassop had been murdered and their bodies concealed, but said there was not enough evidence to commit Sam or anyone else for trial.

So what’s changed? Detective Sergeant Daren Edwards, the head of Maroochydore’s Criminal Investigation Branch, says police have been going back over the evidence; it was why Sam was taken back to Booloumba Creek Rd last year, with the aid of a court order approving the mission.

“It was certainly a bit unsettling for him,” Edwards says of Sam’s visit.

“That’s how (detectives) described it — he appeared very unsettled. There was certainly the opportunity for him to assist more, but he didn’t prove to assist.”

Edwards says the ongoing investigation is a joint effort between local detectives and the state’s homicide squad, and he says they are close to finalising a brief of evidence with the intention of asking prosecutors if there is enough evidence to charge Sam with the murders of Bridge and Glassop.

Police and prosecutors also have another option to consider: if Sam led police to the bodies of the three women, he could escape further prosecution. It would be a deal with the devil, but the recovery of their remains would provide enormous relief to the families.

Such a deal has a recent precedent after Michael Atkins, 54, confessed he knew where to find the remains of Matthew Leveson, 20, and helped police locate them in exchange for immunity from prosecution in NSW.

Dodd says she would be torn if such a deal allowed Sam to be released. “Every day you think about where she is and we just want to bring her home. Obviously we want Jess back, but on the other hand we don’t want him out either, so it’s extremely difficult,” she says.

Glassop’s eldest son, Jed Moore, has embraced the idea; when contacted, he said the most important thing was to find his mum and give her a proper burial.

Failing these options, Sam is set to be caught up in new “no body, no parole” laws. Former barrister and now Court of Appeal president Walter Sofronoff recommended, in his review of the state’s parole system last year, that killers be kept behind bars if they haven’t identified the location of victims’ bodies.

The State Government introduced a Bill in May. The laws will be debated in parliament next week and are expected to be passed. It will be just in time — Sam became eligible for parole last year, but is yet to apply. Unless he reveals the location of Gaudie’s remains, he may never be released.

“There still remains an opportunity for Derek to help himself. He has still got a lot of years ahead of him,” Edwards says.

Wright remains hopeful there will be a resolution, believing the bodies of the three women are not far from Piabun Farm.

“I hope one day we can finally find Jess and give her back to her family. There’s not too many days that go by that I don’t think about Jess and the case, even after all these years.”