Closing the gap: Brenda Matthews tells of her journey to reconciliation as a member of the Stolen Generation

As a child of the Stolen Generation, documentary maker Brenda Matthews knows all-too well what it’s like to walk both sides of Australia’s race divide.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Brenda Matthews knows what it is like to walk both sides of Australia’s race divide.

From seeing her foster parents come home from the hospital cradling a baby with different coloured skin, to stories of Indigenous families sprinkling Pine O Clean on to the dirt floors of tin shacks to show white authorities they could be trusted to raise their own children.

Of watching her father hitchhike or walk for hours to visit incarcerated Aboriginals in prisons to show them there was still hope.

Brenda’s incredible story of being taken from her birth family as a toddler before returning years later is captured in her book The Last Daughter, which has just been turned into a documentary of the same name now streaming on Netflix.

Her story is one of injustice and cruelty, but ultimately, love and healing, and it is why she hopes sharing it will help inspire all Australians to become part of the journey towards closing the gap.

“You can’t reconcile with somebody else if you’re still carrying that hurt and pain so for me I had to realise that reconciliation had to start with myself and the hurt and the pain that I was carrying,” she says from her home in the Gold Coast hinterland.

“That’s when we can start to change ourselves, because you can’t change the nation or the world, without first changing yourself.

“We all have a responsibility of carrying the story of the nation, we all have the responsibility to help heal the wound.

“It can’t only be me, it can’t only be you. It has to be all of us and I think that’s when closing the gap can start.”

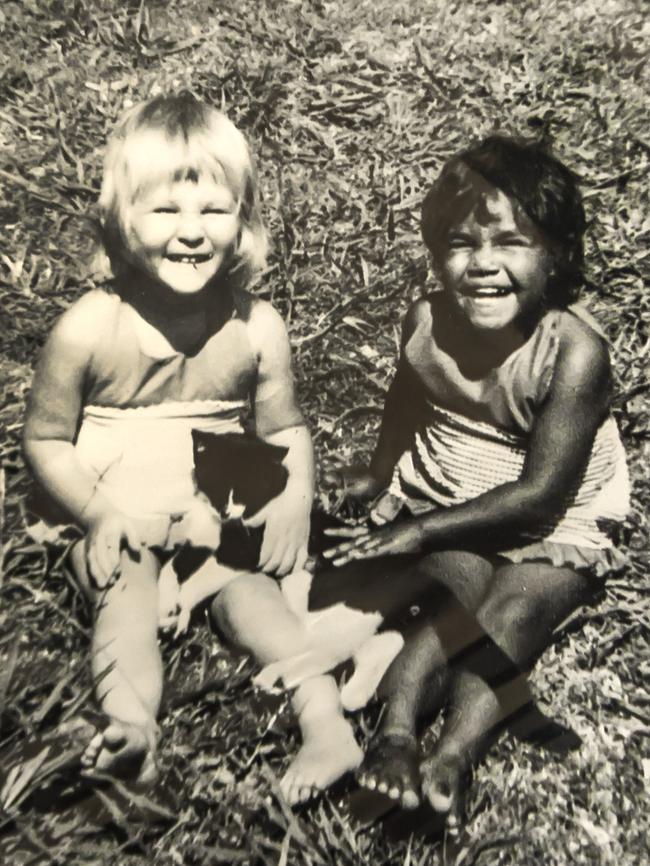

Brenda was just two years old when she and her six siblings were taken from their parents in 1973 from Wiradjuri country in central NSW.

It was a scenario heartbreakingly familiar through the years of the Stolen Generation – only it occurred four years after changes to legislation which were meant to end the controversial practice.

Now 52, Brenda was too young to remember or comprehend the experience, but her older brothers and sisters have told of a happy household with loving parents who were ultimately vindicated when the family was allowed to reunite more than five years later.

“Even just writing the book, going back and listening to Mum sharing about what happened on that day, I just felt so hurt that they were hurt and that they did nothing wrong and they were deemed neglectful parents, deemed criminals,” she says.

She remembers feeling loved in her adoptive foster family in Sydney, but still sensing that “things weren’t the way they were meant to be”.

That feeling became crystal clear when her foster parents brought a white baby home from the hospital.

“That was the first time I really remember questioning that (situation) was when my white mother brought my baby brother home for the first time and I saw that his skin colour was different to my skin so that’s when I questioned why is his skin colour different?” she says.

“I felt like an intruder in their house too because I wasn’t the same colour as they were and that’s when they told me that they weren’t my biological family.”

She remembers feeling joy at the eventual reunion with her birth family, but the ordeal of what they had all been through was “buried” for many years.

“I think I was about 15-16 and Mum told us that we were part of the Stolen Generation and we were stolen children,” she says.

“We didn’t really know about the Stolen Generation or understand that, so in a sense it was hidden … because it was too painful for them to talk about and I’m so glad they waited until we were old enough to understand.”

She heard other stories of the Stolen Generation, stories which meant she never looked at floor cleaners or lavender bath soap the same way again.

“Mum tells a story, and I hear a lot of stories like this from the reserves and the missions that they used to be on, and they had dirt floors and tin shacks and even when they were clean, they weren’t clean enough so the black fellas would sprinkle Pine O Clean on the dirt to make it nice and smelly for the white fella to come in and say “your house is up to standard” and if it wasn’t they’d take your children away,” Brenda says.

“To be scared that someone is going to come in and take your children away so you have to sprinkle Pine O Clean on the earth, I can’t even fathom that, what they had to go through.

“My mum used to use Pine O Clean on our lino floors and it would be the lavender one so that smell through the house, even … with lavender bath soap – always reminds me of those stories.”

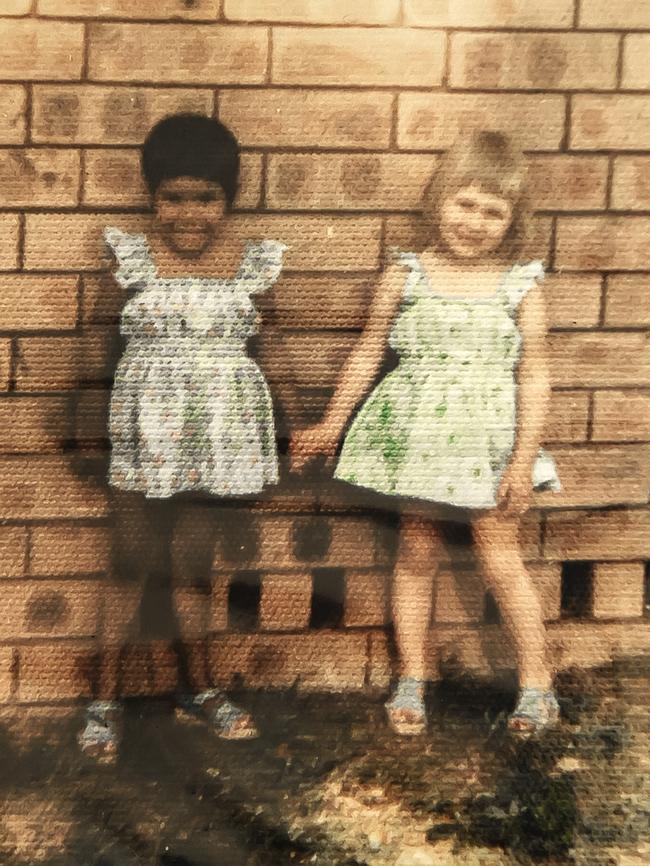

After 40 years grappling with her divided upbringing, Brenda eventually reconnected with her foster family and now feels enormous love from both sides.

“It’s very hard if you’re caught between two worlds and have two families that are different colours, (but) I’m happy because I’ve been able to find the truth about myself,” she says.

“Going through it (at the time) I didn’t understand it, nobody explained anything to us, you know, on either side, so just reliving the trauma of that over and over again has helped me to understand that “hey, I had love here in both families”.

“And they really did care about me.”

While she has peace with her own story, she knows not everyone feels the same way.

She still sees division in things like the attitude to Welcome to Country ceremonies, through to the way society operates at large.

“The white system outweighs the black system and that’s where we struggle every day as Indigenous people because they’re not our practices and when you can’t practice your practices, who are you? Where do you belong?” she says.

And like many Indigenous people, she is acutely aware of the higher incarceration rates among her people.

It inspired her father Gary, a deeply spiritual man, to travel to prisons to visit Aboriginal inmates to give them support and hope.

“He could see that they needed help, they needed encouragement,” she says.

“He just wanted to share the love and the forgiveness and that kind of attitude is what’s made me who I am today.”

But she also sees progress.

“For a long time us as Indigenous people had to leave our spiritualty and our Aboriginality at the doorways and hallways … but I do see now that there is more Indigenous stuff coming into the system and I think when we start to embrace the two cultures, and that there is a balance there, that you know we will be able to move forward,” she says.

“I sit there when they have NAIDOC Week, and it shouldn’t just be then, but listening to the didgeridoo playing and see the young ones coming out dancing and being proud of their culture and that makes me cry, that softens my heart, because for a long time, our practices weren’t allowed in these places but now they’re coming in so to see these young ones coming up and learning their culture … gives me a sense of hope and love in my heart.”