When the applause goes quiet: Why our athletes die twice

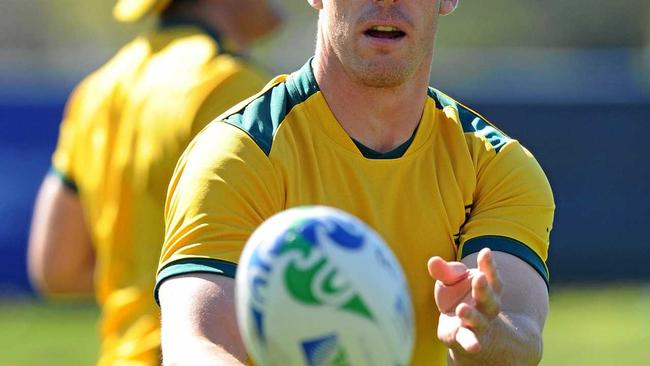

THE death of Dan Vickerman has given a tragic depth to the observation that a professional athlete dies twice and the first time is the day they retire.

Central & North Burnett

Don't miss out on the headlines from Central & North Burnett. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE death of former Wallaby Dan Vickerman has given a tragic depth to the observation that a professional athlete dies twice and the first time is the day they retire.

The 204cm Vickerman, renowned for his intensity on the rugby field and his friendly nature off it, appeared to have handled the transition in textbook fashion. He'd even taken time out mid-career to pursue a university degree in land economics at Cambridge.

When persistent leg injuries forced him out of the sport in 2012, his transition from professional sport to a career in commercial real estate appeared seamless. On the strength of this, the organisers of the Crossing the Line sport summit in Sydney at the end of last month had advertised Vickerman as a keynote speaker.

But the demons were lurking, as former Wallaby Owen Finegan acknowledged in the days after Vickerman's death at his Sydney home on February 18.

"I think everyone was shocked by it. It was devastating - we all play on an old boys team called the Silver Foxes and Dan had expressed a number of times how difficult his transition was and it is difficult for a lot of professional sports people, especially when you've had 10 or more years at the top of the game," Finegan told the press.

The managing director of the Final Whistle, Greg Mumm, whose company helps athletes through these transitions, signed Vickerman up to speak at the summit. He said his company focuses on the career aspects of transition rather than mental issues.

"Athletes experience a range of challenges physically and mentally at the end of their careers," he said.

"Their hormones change almost overnight. There's a decrease in the production of endorphins. There are so many areas where everything changes at the end of a career.

"There's the mental aspects, career, finance and relationships."

He said Vickerman's tragic death showed that "having it all" - the education, the job, the family - sometimes was not enough.

"Athletes are used to disguising it when things aren't going their way," Mumm said.

"They're trained to respond by pushing harder when things get tough. That's really helpful when you're lifting weights or on the training paddock, but it's not helpful if you're struggling with mental issues.

"It's important to learn to ask for help if you're struggling."

Some athletes, like champion British cyclist Victoria Pendleton, embrace retirement. Pendleton said she couldn't wait to get on with the next part of her life.

But for many, their experience is more like that of boxing legend Sugar Ray Leonard, who famously said, "Nothing could satisfy me outside the ring ... there is nothing in life that can compare to becoming a world champion, having your hand raised in that moment of glory, with thousands, millions of people cheering you on."

Mumm said it was important athletes took time to investigate what might interest them after their careers were over and do it sooner rather than later.

"We recommend they get experience in an industry and test it by spending some time in it before making a decision," he said.

Mumm said athletes coming into retirement tended to see everything in life as winning or losing, which could create problems.

"Often they forget how long it took them to be successful in their sport. Sometimes they have to be reminded it's okay to make mistakes," he said.

Mumm said there were strategies that athletes could adopt to help overcome this.

"Some athletes find it helpful to be reminded about all the things they couldn't do because of sport," he said.

"It is often simple things like remembering sacrifices - going out with friends or sleeping in - that can make the transition positive."

Professional sport has also grown exponentially in the past two decades, which has fundamentally changed people's attitude to playing the game.

"It used to be there were only three or four sports that could support full-time professional athletes," Mumm said.

"But over two or three decades more sports have become fully professional and given more athletes a chance to consider sport as a career."

Mumm, who is the brother of Wallaby forward Dean Mumm, was one of those until injuries put an end to it.

"After six knee operations at the age of 19, suddenly the sports career was all over," he said.

He said it was just as important to help young people whose careers were cut short to make the transition.

"Many of these young athletes have focused entirely on sport and don't have anything to fall back on when they find out they are not going to make it, or they get injured," he said.

"It can be just as devastating for them that their careers never get going."

The reluctant retiree

Grafton's Brent Livermore, who captained the Australian men's hockey team that broke its gold medal drought at the Athens Olympics in 2004, did not take retirement easily.

"To this day I have never actually announced my retirement," he said last week.

To his frustration, Livermore found new Kookaburras coach Barry Dancer and the selectors making the decision for him.

"I was still recognised as one of the best 11 hockey players in Australia, but I was told the coach was looking for new players while building for the London Olympics in 2012," he said.

"It was hard to accept. I was still playing at my peak of performance, I was still a leader and player in the group, but I wasn't flavour of the month with the coach."

While the Kookaburras might not have wanted him, he was in demand with hockey leagues around the world and took up offers to play in the Netherlands, India and New Zealand as his playing career wound down.

"In a way I was lucky: because of the money in hockey, or lack of it, I was always aware I would have to prepare for life afterwards," he said.

Recognising a return to the national colours was unlikely, Livermore did a business studies course and networked assiduously.

"While I was still competing I knew I had to utilise the profile I had," he said.

"There are also many things professional athletes do that transfer to life after sport.

"In a way sport was my apprenticeship so I could go into a higher role in business or work, without starting out again at the bottom of the ladder."

Livermore was in demand in the corporate speaking circuit and worked as a property investment consultant, all the time continuing as a hockey coach and player.

The hockey family has reached out to Livermore and he once again finds himself wrapped in its arms as a head coach at the NSW Institute of Sport and ranked as one of the top seven coaches in the sport.

"At the start of the next Olympic period I could be head coaching with the Kookaburras, or overseas as a head coach of a team. But if Hockey Australia goes crazy and decides for whatever reason it didn't want me, there are other things I can do."

The world's his oyster.

Being a professional squash player has opened the world up for Yamba's Cameron Pilley. At 34 he's closer to the end than the start of his sports career and has started to imagine what retirement might be like.

"I think I will be both happy and sad at the same time," he said.

"In some ways I'm looking forward to leading a 'normal' life of settling down, not travelling as much, getting into a regular daily routine and not putting the body through so much pain during training and competing.

"On the other hand, however, that is exactly what I think I will miss - the travelling, the different cultures, seeing friends from all over the world. It's exciting to see what the future brings."

But Pilley hasn't tried to imagine how he might feel the day after he retires.

"Honestly, I don't know. I hadn't thought about it until you asked the question, and I really can't answer it," he said.

"Possibly a sense of accomplishment or an 'end of a chapter' type feeling."

Pilley, ranked 14th in the world in men's squash, who has won a Commonwealth Games gold medal and holds the record for the hardest hit squash ball at 175kmh, said he would miss a lot of things about his sport.

"I will miss the travelling for sure," he said.

"Going to airports, getting flights, exploring different cities around the world.

"The biggest thing I'll miss, however, is the adrenaline and the high of competing on the world stage in front of a huge crowd. Competing in iconic locations, being a part of a great match, and being applauded by the crowd for your efforts is something special."

Pilley feels his sport has equipped him with some useful skills for his future life.

"As a squash player you need to be able to make quick decisions," he said.

"Sharp reflexes, fast feet, quick hands and then being able to play the right shot, all at the same time. I think this type of quick decision making and thinking will be very valuable post sports career.

"I come into contact with so many people from so many different cultures that the ability to communicate well is also a valuable skill I have learnt over the years."

Ideally Pilley would like to stay with the sport that has given him so much and return something to the game.

"I would like to stay involved with the sport as I would love to help Australian squash become a powerhouse on the world stage once again," he said.

"But who knows what opportunities may arise? Coaching is something I am interested in, especially coaching aspiring pros.

"As a rule you never say never, so I will look at all options once I have retired."

Pilley said he has networked well during his career which should give him options in the future.

"I haven't done anything stupid with my money, so that is also a good thing," he said.

"I met my wife on tour and we are settled which provides a lot of stability away from squash."

On the down side, squash, like many professional sports, does not provide any mentoring or coaching for players transitioning to retirement, but there has been talk of changing this.

"It's actually something that the sport is looking to improve," Pilley said. "They are actively trying to help us players think about the future and plan for life after sport."

Phone Lifeline on 13 11 14 for confidential crisis support.

Originally published as When the applause goes quiet: Why our athletes die twice